A shorter version of this piece was first published on The India Cable – a premium newsletter from The Wire & Galileo Ideas – and has been republished here. To subscribe to The India Cable, click here.

On the face of it, the interview Narendra Modi gave ANI on the eve of the first phase of polling for the Uttar Pradesh assembly election is a violation of India’s election law, which prohibits the display of “election matter” in any form in the 48 hours preceding the closing of polls.

“Election matter,” Section 126 (3) of the Representation of the People Act says, “means any matter intended or calculated to influence or affect the result of an election.” In the last 48 hours, candidates are simply not allowed to put out election matter, whether it is through TV or a theatrical performance. Frankly, I don’t know which of these two categories Modi’s interview falls into but the answers he gave (and the questions he was asked) were clearly calculated to influence or affect the result of the UP election. Unless you live on Mars, or Mangala.

126. Prohibition of public meetings during period of forty-eight hours ending with hour fixed for conclusion of poll.—(1) No person shall—

(a) convene, hold or attend, join or address any public meeting or procession in connection with an election; or

(b) display to the public any election matter by means of cinematograph, television or other similar apparatus; or

(c) propagate any election matter to the public by holding, or by arranging the holding of, any musical concert or any theatrical performance or any other entertainment or amusement with a view to attracting the members of the public thereto, in any polling area during the period of forty-eight hours ending with the fixed for the conclusion of the poll for any election in the polling area.

(2) Any person who contravenes the provisions of sub-section (1) shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to two years, or with fine, or with both.

(3) In this section, the expression “election matter” means any matter intended or calculated to influence or affect the result of an election.

This was not an interview with the prime minister of India about the state of the nation. It was explicitly about the Bharatiya Janata Party’s approach to the UP election (as well as the other four state elections), and Modi’s answers made it clear that he was doing his best to influence the results in favour of the BJP.

In 2017, the Election Commission had invoked Section 126 and directed the police to take action against various TV channels for broadcasting an interview that Congress leader Rahul Gandhi gave on the eve of the second phase of the Gujarat assembly elections that year. Curiously, however, it withdrew that notice four days later – perhaps because it was advised that Section 126 applies to candidates and their supporters and not to the media – and said it would look into proposing suitable amendments to the RP Act. Nothing has been seen or heard about this topic since then. Even though this time around, the EC reiterated the bar on the display of election matter in the last 48 hours before polling ends, Narendra Modi appears to have been confident the EC would not act against him.

If the EC has conveniently forgotten its own rulebook – despite more than half of the interview, including the very first set of questions, being all about the UP elections – ANI too was more than eager to give Modi a free ride.

The hour-long interview was full of the usual softball questions we have come to expect. The two or three half-decent questions asked were phrased so shabbily and even apologetically that they might as well not have been asked.

The toughest observation ANI editor Smita Prakash managed to make was when she referred to the continuation of Ajay Teni as minister despite the alleged involvement of his son in the killing of farmers at Lakhimpur in UP. Except that she did not really ask it as a question, so Modi didn’t have to answer. And Prakash, expectedly, didn’t follow up. Modi spoke about the farmers’ opposition to his government’s farm laws and the importance of samvaad or dialogue but he was not asked about his failure to meet with and discuss the laws with the protestors or about the death of 700 farmers that he had so callously dismissed – according to one of his own party’s governors.

To give her credit, Prakash feebly brought up the allegation that Modi uses Central investigation agencies to harass the BJP’s political opponents at election time, but allowed him to get away with the absurd and easily refuted claim that the ED and CBI work independently of the government and that any raids at election time on opposition leaders and their family members were a coincidence since “there are always elections going on”.

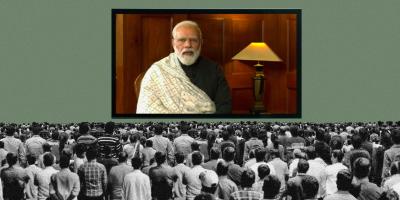

A screengrab from Smita Prakash’s interview with Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Photo: Screegrab via YouTube/ANI

Predictably, the fierce anti-Muslim and anti-Christian campaign being pursued by the BJP and its affiliates around the country – the recent calls for Muslim genocide, the attempted ban on public namaz or the hijab in school – found no explicit mention in the interview. Nor did the speeches Modi, Amit Shah and Yogi Adityanath themselves have made in the election campaign, which make ample use of anti-Muslim dog-whistles. Instead, Prakash asked a roundabout question about how the media is full of reports of polarisation and of Muslims feeling insecure. Framing the question in this way allowed Modi to cast aspersions on the media – ‘Why the media does what it does and who directs and commands them is not something I wish to comment on’ – without forcing him to engage with the issue or address his own sins of commission and omission as prime minister.

Prakash reminded Modi of the criticism that his government is not respectful enough of India’s regional diversity, a question he parried by misrepresenting himself as a great champion of federalism. And his misrepresentations on the COVID-19 lockdown –where he pinned the blame for the mass exodus of workers from urban centres on the opposition – also went unchallenged. A simple question – ‘Why didn’t you discuss the national lockdown with state governments, and plan and announce immediate relief measures so that the exodus could have been avoided?’ – was unasked.

His government’s biggest defence and foreign policy mess – China has occupied Indian land along the boundary in Ladakh that it had not done before – also went unasked. The fact that China did not figure in the prime minister’s last two interviews either – to OPEN magazine in October 2021 and Economic Times in October 2020 – tells us that key sections of the Indian media lack basic news sense or spine (or both), and that Modi himself is reluctant to be held to account for what has happened.