The Perfect Face for All Occasions

Is Narendra Modi's face ever able to get over the instinct of seeing invisible cameras everywhere, of wanting to be seen everywhere?

Narendra Modi at a work site on the banks of Sabarmati river in Ahmedabad. Credit: PTI/Files

In the few hours that our toiling prime minister presumably has to himself in a day, what must be the set of his face? I do wonder sometimes. Does the face reclaim what it remembers as the look innate to it before it was overtaken by the deluge of looks given to a camera for every screen possible? Or is it resigned to being just one among the many looks in a scenario where the ‘original’ has no meaning, for each projection carries the stamp of an original.

What does a face, accustomed as it is to every angle of the camera frame, do when there is no camera around? When the aperture becomes an essential cue for the look the facial features must school themselves in so as to project the image at the core of the prime minister’s politics, is his face able to feel itself in the absence of backlighting?

More to the point, is his face able to get over the instinct of seeing invisible cameras everywhere, of wanting to be seen everywhere, of casting each moment as a Momentous Moment in the History of Mankind? Remember the relentless tableaux of images – like a constant Republic Day parade – that we have witnessed in the past three years: the well-crafted solemnity and unflinching expression at his prime ministerial coronation, cheek bones like high ridges and eyes looking into the distance, making people exclaim, ‘what gravitas!’; the man with the ‘strength’ to become tearful in parliament; the face of the ‘epochal man’ immersed in ochre in the ghats of Banaras; the statesman who unburdens himself to smile every now and then, especially when there are children around; the face of mortal anguish as he talks about the guru he so surgically sidelined; the face of a man determined to appropriate ritual and civic encomium by making India ‘swachh’; also the face of a statesman busy trying to cultivate a look that is acceptable to all, of ‘rising above’ everything (by not commenting on cow lynchings, and by landscaping meetings with foreign dignitaries at Sabarmati Ashram).

Prime Minister Narendra Modi poses for selfies with reporters during the Diwali Mangal Milan at BJP headquarters in New Delhi. Credit: PTI/Files

One wonders if it’s a strain for the facial muscles, however mobile, to compose look after look, for projection against carefully-chosen backdrops. Or maybe the face is content to be overrun by the projected image that lives in the light of power.

I have a friend who says that like the rest of the body, the face too has a muscle memory – a set of memories for facial muscles to draw from; veritably a map of furrows, grooves and lines that the features have made over a period of time. In the same breath my friend says that it is not so very difficult to fashion new memories for the facial muscles to follow. She says it is like acquiring “new facial habits”.

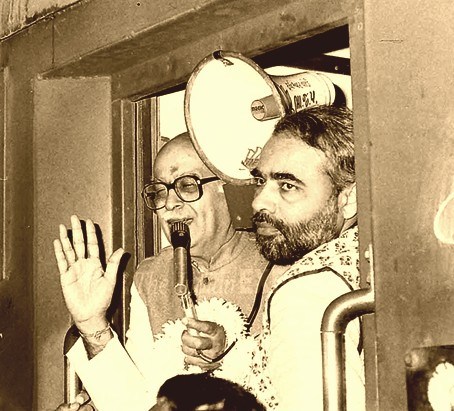

Narendra Modi with L.K. Advani during Advani's rath yatra. Credit: Twitter

It’s an intriguing thought. In the prime minister’s case that would mean the new facial habits of power. The earliest photograph that I could lay my hands on, on the internet, was of Modi as L.K. Advani’s assistant during the rath yatra of 1990. The spotlight was on Advani, who was soaking in the warmth of the camera, with precious little of it straying towards a younger Modi despite the fact that he was standing right next to his guru, with a somewhat shuttered look on his face. It was a face that was not lit by the arc lights of power and adulation as yet. His face spoke merely for him.

By 2002, new facial habits started becoming visible. It became a face moulded by the power Modi wielded as chief minister. His face was no longer merely his own; it was equally the face of the majority community. Every individual grouse, explained as the oppressive handiwork of the minority, became one more element to the construction of the look of a ‘Hindu hriday samrat’. Nothing shuttered about the face any more – characterised by unconcealed aggression, it became the face of uncompromising prejudice, his mouth set in a hard line.

The political persuasion Modi comes from works on the premise of a strong, or authoritarian, ‘father-figure’ face. Resting on the foundation of myth-making and an active dislike of facts, it perfects the art of identifying the face of the other as well. A beard and skull cap is enough to identify the ‘enemy’, and every such identification adds one more element of ‘strength’ to the leader’s face, with the image of an avenger or punisher. The stern set of mouth hints at the resolve of one determined never to be cast in the shade or left feeling powerless – a determination that is personal and ‘civilisational’ at the same time. Imagine a cartoonist furiously cross-hatching to give mass and weight to the image, highlighting the mouth, for it was a time of strident communication.

Once the communal hues had suffused the face enough to reflect the reality of a state in which the minority has been made irrelevant in the state’s politics, the triumphal light in Modi’s eyes signalled another level of myth-making – that of ‘vikas purush’ and at a stretch ‘sadbhavna’ purush. In the period 2002-2013, Modi mastered the skill of projecting before the camera and more importantly, blocking all the angles from which the slightest raised eyebrow could wriggle in. His face and the camera were in complete sync – the image reigned supreme.

A mythology of power and omnipresence was created through the literal multiplication of his image – on television, on hoardings and billboards, on pamphlets and last but not least on the faces of audiences during election rallies as they made his face their own by wearing Modi masks.

During the 2012 elections, he moved from the low-tech mask to being projected on screens across cities through holographic technology and satellite link-ups. Charisma works in different ways – sometimes as a physical presence and sometimes as a holographic image which has all the advantages of a one-way communication coupled with the aura of existence on a ‘higher’ plane. Modi’s face projected his ambitions onto his audience and equally was the embodiment of their fantasies.

Supporters of Bhartiya Janta Party wear Narendra Modi masks in Ahmedabad, December 23, 2007. Credit: Reuters/Amit Dave/Files

The look on his face also changed in the course of this decadal journey, becoming smoother. An appropriate look for one striving to be a man for all seasons and all people as he made the jump from the regional to the national stage. The face that was used to create a rapport with the audience through inside jokes and by projecting derision towards opponents to forge the face of Gujarat, sported the face of an ‘Indian’, often slipping into the trench-like grooves of the old face of corrosive prejudice. On the plus side, he even learnt to stretch his lips into a smile.

The prime ministerial face that we glimpsed three years ago was a satisfied face, for it was now the face of the country, lovingly pampered by power. Moreover, there was a new international grid to explore, with immense potential for an entirely new batch of looks. No wonder that for a person who lives by the image, the politics of the country itself became self-referential, an ode to his image.

The only dilemma for Modi is that every now and then he confronts a situation where it’s a question of one self-image locked in confrontation with another equally strong self-image. Remember the time when the image of the ‘chai bechne wala’, people’s man, came up against the look of a man who wears ‘a ten-lakh suit with his name embroidered on it? Both images had been created by him.

The prime minister’s self-referential view of politics ensures that every time there is some show of opposition to his government or party, he naturally sees it as an attack on him, on his image. That is the way he has crafted his national scenario. That is when the duel of images takes place. Take the recent Gujarat election campaign, for instance, when all of a sudden the avuncular ‘see no evil, hear no evil’ look of a leader at the helm of national affairs was overtaken by the street-fighting face, the dull sheen of communal rancour spoiling the carefully arranged ‘Indian’ mien.

This is a face-off that Modi is increasingly bound to encounter in a narrative where the image is the politics.

One wonders whether the prime minister’s face reflects this worry – provided it is able to free itself of the image – in the few hours he presumably has to himself in a day.

Chitra Padmanabhan is a journalist and translator.

This article went live on December fifteenth, two thousand seventeen, at twenty-one minutes past two in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.