Polarisation Is Bad for India and the US. But Its Effect in India Will Be Catastrophic

It is a well-known fact that India and the United States – respectively the world’s largest and strongest democracies – are among some of the most polarised countries in the world today.

Polarisation impacts both society and its politics. While the sharply divergent views and interests between groups of people need not lead to violence, there is no question that polarisation weakens social cohesion. Otherwise, we would have heard about polarised societies that were also cohesive at the same time.

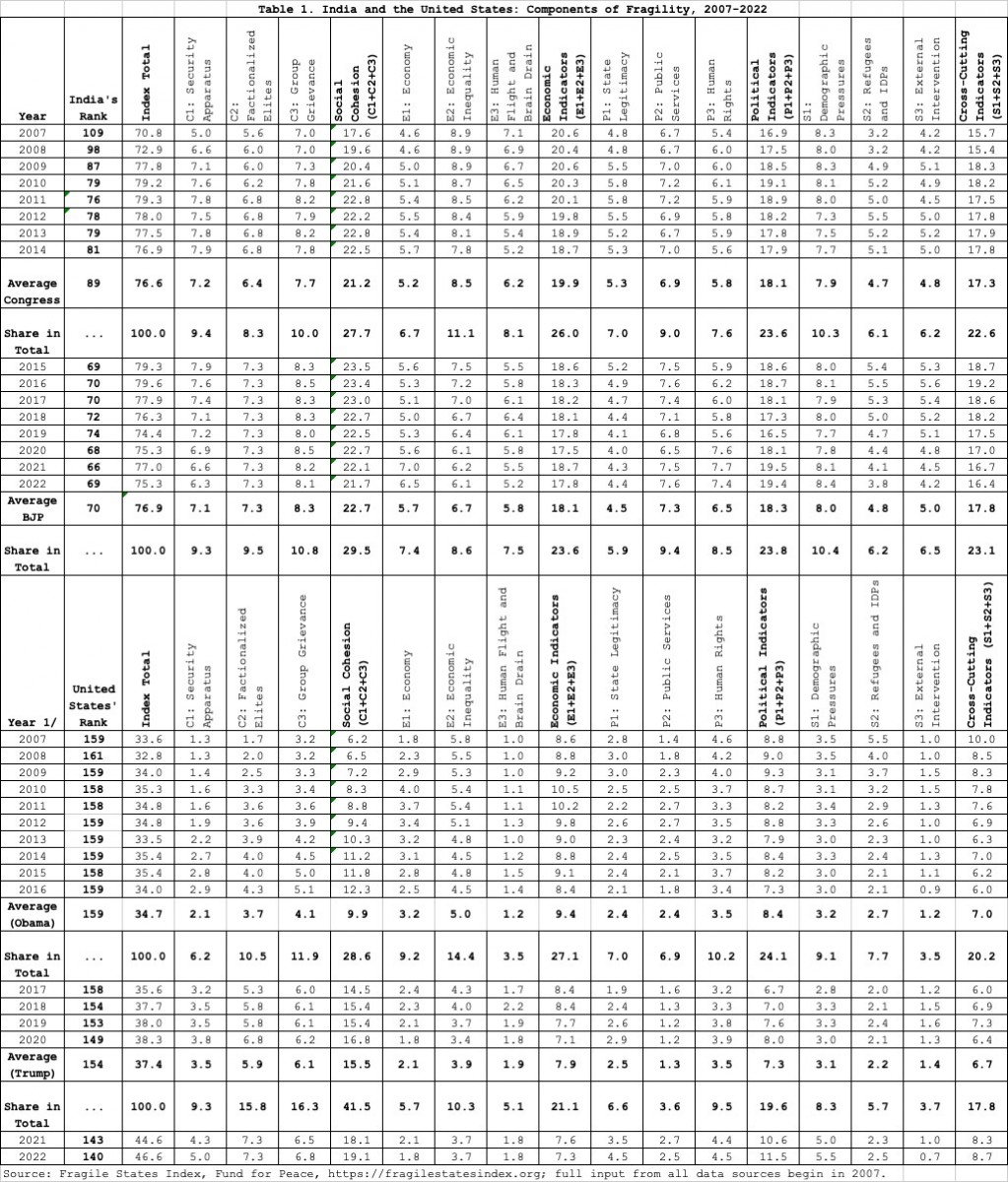

The attempt here is to explore whether the impact of polarisation and political transition in these two countries can be captured by the Fragile States Index (Table 1). Of course, the measures of polarisation described by Thomas Carothers and Andrew O’Donohue in their landmark 2019 book (such as electoral poll data collected through surveys) are only available for a few countries. There are also significant issues related to the cross-country comparability of polling data given differences in survey methodologies.

The 12 primary indicators of the FSI are grouped into four broad indicators, namely social cohesion, economic, political, and crosscutting. In this framework, rising indicator scores – each subject to a maximum of 10 – contribute to an increase in state fragility.

India: From Manmohan Singh to Narendra Modi

The data indicates that social cohesion in India started to deteriorate in 2009, several years before the General Election of 2014 which swept the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) into power. Actually, given an average lag of 12 months in the collection, verification, and processing of millions of bits of qualitative and quantitative information that are necessary to calculate the indices, the deterioration in social cohesion probably started in 2008.

Several studies of polling behaviour in India have shown that Congress lost the 2014 election due to the significant loss of support among Hindus.

For instance, Christophe Jaffrelot, Niranjan Sahoo, and Milan Vaishnav have suggested that there was a growing resentment among Hindus of the Congress's supposed "pseudo-secularism", which they saw as neglecting their concerns and using minorities as a vote bank rather than acting out of a genuine concern for their social uplift. During the year leading up to the 2014 elections, political in-fighting and fractiousness increased and the problem of refugees in the east (mainly from Bangladesh) worsened.

Also read: Under Modi, Politics of Polarisation Takes Over Development Narrative During Pandemic

These are reflected in a deterioration of the political and cross-cutting indicators. While economic indicators, on the whole, continued to improve, these measures are too broad and they do not capture the extent to which the marginalised sections of society benefit.

In fact, the BJP was successful in convincing the 'lower' caste Hindus – who typically voted for the Congress – that its 'vote-bank politics' did not lead to their economic and social progress. These profound political realignments set the stage for the rise of Hindu nationalism and the unprecedented popularity of Modi and the BJP.

After coming to power, the BJP started various social programmes (such as the Jan Dhan Yojana and the Ujjwala Yojna) and direct cash transfer payments to ensure the continued support of the poor. Meanwhile, improving economic conditions in Bangladesh, tighter border controls, and rising political and social sentiments against undocumented immigrants (particularly in the border states like Assam and Tripura) contributed to a decline in the refugee problem.

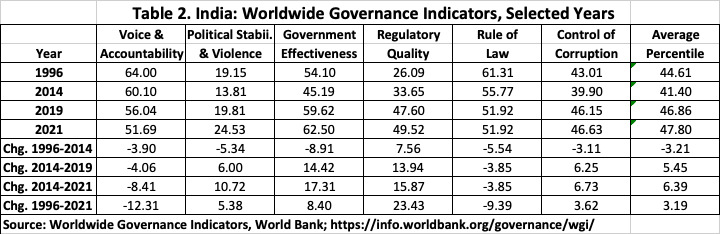

Table 2 shows India’s percentile scores in each of the six dimensions of governance starting in 1996, the earliest year for which the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGIs), compiled by the World Bank, are available. It should be noted that, unlike the FSIs, a decline in percentile score reflects a worsening of governance relative to other countries in the world. The six dimensions of governance are voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption.

The data show that between 1996 and the 2014 General Election, there was a deterioration in every aspect of governance except regulatory quality. This must have also weighed on voters' minds as they headed to the polls in 2014.

In contrast, the BJP has continued to improve governance through the 2019 General Elections, although thus far, it has scored well below the Congress's score on voice and accountability. Under the BJP, the latter slid by 8.41 percentiles as a result of the government's muzzling of the media and freedom of expression. This is also consistent with our observations. Modi seems to take decisions without much consultation and appears to be far less accountable than the Congress leadership ever was over the period in question.

Finally, the rule of law, which is a crucial aspect of governance, has undergone a steady deterioration under both governments although recent data indicate that the BJP may be trying to arrest this trend. In any case, available WGIs indicate that since coming to power in 2014, the BJP has managed to improve India's governance by an average of 6.39 percentiles compared to a deterioration of 3.21 percentiles under the Congress party.

The WGIs indicate that improvements to political stability and the absence of violence, or control of corruption has come about at a glacial pace (around 5 percentiles or less in 25 years).

United States: From Obama to Trump and Biden

Similarly, in the United States, we see a significant deterioration in social cohesion during the Obama years (2009-2016) led primarily by a sharp uptick in Group Grievance and Factionalized Elites. The latter considers the fragmentation of state institutions along various lines such as race and class and the resulting gridlock between these ruling elites.

But, unlike in India, the weakening of cohesion in the United States was led by what the Obama administration could not do rather than by what it did. As Carothers and others have noted, a policy gridlock brought on by Republican opposition to Obama’s legislative agenda was mainly responsible for his failure to keep many campaign promises.

Former US President Barack Obama. Photo: 2020 Democratic National Convention/Pool via Reuters

Moreover, the issue of police violence against African Americans during Obama’s second term generated extreme divisiveness, which is reflected in a significant worsening of the Security Apparatus indicator. While economic conditions deteriorated in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, they started recovering in 2011. However, the improving economy under Trump could not forestall the weakening of social cohesion.

Thus far, the Biden administration has not been successful in reversing the worsening trend related to America’s security establishment which started under Obama and continued to deteriorate under Trump. To make matters worse, the Biden administration has also not been successful in reversing the worsening of Factionalized Elites and Group Grievance, which have continued to increase since the early years of the Obama administration. These underlying factors are responsible for driving the continuing weakness in social cohesion. That does not bode well for Biden and the Democrats in the upcoming mid-term elections in November 2022 or the Presidential Elections in 2024.

While we do not have a crystal ball, our reading of the implication of a persistent decline in social cohesion for the Democratic party is consistent with the prognosis of other economists. For example, Dani Rodrick, an economist at Harvard’s Kennedy School recently wrote that those who voted for Trump after voting for Obama, a group of voters he called “switchers”, were driven by economic insecurities and are hostile to all aspects of globalization including trade, immigration, and finance.

We think this feel-good backlash is likely to remain a “backlash to nowhere” without concrete policies to mitigate the fallout of globalisation which neither party has managed to spell out much less deliver. As for globalization, we expect it to grind on despite calls for a decoupling from China.

Why do Indians have a lot more to worry about?

Typically, majoritarian parties tend to alienate minorities through harsh political rhetoric and discriminatory treatment. But, liberal parties could also weaken social cohesion by alienating significant portions of their traditional electoral base. The FSI framework reveals that this undercurrent of dissatisfaction with liberal parties started brewing years before the political ascension of Hindutva in India and Trumpism in America.

However, the ushering in of these illiberal governments did nothing to improve social cohesion. On the contrary, the FSIs indicate that both Modi and Trump made matters worse – social cohesion and fragility have continued to worsen due to rising group grievance and increasingly factionalised elites. In fact, the polarisation wrought by both liberal and illiberal governments seems to have had a compound effect, turning the two into some of the most polarised countries in the world today.

Former US President Donald Trump and PM Narendra Modi at Hyderabad House. Photo: PIB/Twitter

Unfortunately, the worsening Hindutva-driven polarisation portends a darker future for India than what illiberal democracy could possibly impose on America. The main reason is that while American democracy is endowed with a much stronger rule of law, independent institutions, and an effective opposition party, such checks and balances are either non-existent or weak in India.

The Congress Party is largely seen as a self-serving fiefdom short on ideas on how to become an effective opposition let alone defeat the BJP. A younger generation of Indians, which cannot relate to its Nehru-Gandhi lineage, has moved on. Meanwhile, a widely popular Modi, untethered by the guardrails of a strong democracy, is becoming increasingly autocratic. The slide in India’s voice and accountability supports this observation.

Recently, at the 77th session of the UN General Assembly in New York, India’s external affairs minister S. Jaishanker declared that India resolved to become a developed country in 25 years. While the objective is laudable, FSI data shows that overall fragility worsened precipitously by 40 ranks since 2007, 12 of them under Modi’s watch. We do not see how India can become a developed country by becoming more fragile.

Also read: The Two ‘Democracies’ of India and US: How Similar, Yet How Different

Meanwhile, it is difficult to reconcile Modi’s oft-stated policy of “sab ka sath sab ka vikas” or “collective effort and shared prosperity” with evidence of a significant weakening of social cohesion led by rising group grievance. In fact, several eminent economists such as Abhijit Banerjee, Raghuram Rajan, and Amartya Sen expect Hindutva-driven polarisation to effectively hamper India’s ability to become a developed country.

China, with an economy that is more than five times the size of India’s, would not automatically become a developed country once it overtakes the US economy, perhaps within a decade. Nor is high per capita income a qualifying measure. Qatar, which has a higher per capita income than the United States, isn’t a developed country either. Without progress on various fronts, India too would not become a developed country even if its GDP were to surpass those of China and the United States at some point in time.

GDP, or for that matter GDP per capita, says nothing about income distribution. In order to actually become a developed country, India should focus on delivering inclusive growth that is environmentally sustainable. According to the IMF, the average per capita income of the G7 advanced countries was US$56,350 in 2022. India would have to reach this income level on a much more equitable basis thereby eradicating its endemic poverty. India would also need to achieve lasting improvements in all six dimensions of governance to reach a state comparable to advanced countries. Judging by the way things are going, we do not expect India to graduate to a developed country within that time.

Politicians can either pursue policies which alienate or those which foster inclusion and make the country more resilient. But, they cannot polarise and make countries great again. Rather, polarisation has left countries without the social cushion to absorb the coming economic shocks.

For countries to reach their full potential and play a larger role on the world stage, the journey must traverse the long road to social cohesion. Given India’s dizzying diversity, its constitution embodying the universal, secular values of liberty, equality, and fraternity, remains the best way forward. As for the US, we expect polarisation to not only further weaken the fabric of its diverse society but jeopardise its leadership of the rule-based international order.

Dev Kar, a former senior economist at the International Monetary Fund, is chief economist emeritus at Global Financial Integrity and a fellow at Yale University. His book, India: Still A Shackled Giant, was published by Penguin Random House India in October 2019.

This article went live on November ninth, two thousand twenty two, at thirty minutes past nine at night.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.