A penny should drop whenever a sitting prime minister starts lamenting the imbalance between rights and duties of Indian citizens. And, if the prime minister happens to be a man who unchallengingly occupies the commanding heights of Indian politics, it is time to prick up our ears to the autocrat’s knock on the Republic’s door.

A few days ago, Prime Minister Narendra Modi argued that too much insistence on rights and too little emphasis on duties has weakened India. This diagnosis was delivered, ironically enough, during a celebration of the 75th year of our birth as an independent, democratic nation. The implication, dark and ominous, is that this perceived source of weakness ought to be plugged.

The prime minister’s thesis – patently at odds with the basic structure of the constitution – calls for reflection on what makes a nation strong. But how does a nation’s “strength” or “weakness” get assessed? And who is doing the accounting?

Recent history has a few sobering answers for us. Let it be recalled that not too long ago there was a strong, powerful state known as the Soviet Union. Its founding leadership was uncompromising in its conviction that the very raison d’etre of the Soviet republic was the perpetuation of the gains and achievements of the Russian Revolution of 1917. Accordingly, a “dictatorship of the proletariat” was institutionalised and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union gave itself the monopoly of power. Under the constitution, adopted in 1936, Soviet Citizens had no civil and political rights of the kind people in democratic countries take for granted but were assigned duties to the Motherland.

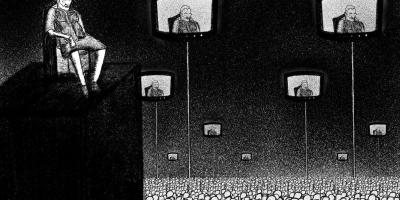

After the Second World War, the Soviet Union did indeed become a superpower – not just a military powerhouse but also an ideological model, inspiring millions and millions of suppressed people in one imperial colony after another. Moscow had a voice and veto over global governing arrangements. So far, so good. Yet within just five decades, that strong Soviet state – characterised by a dominant leader, heading a dominant party, flaunting a dominant ideology, insisting on unquestioned authority for itself over all citizens – collapsed ingloriously into a heap of a dozen odd states.

After the Second World War, the Soviet Union did indeed become a superpower – not just a military powerhouse but also an ideological model, inspiring millions and millions of suppressed people in one imperial colony after another. Moscow had a voice and veto over global governing arrangements. So far, so good. Yet within just five decades, that strong Soviet state – characterised by a dominant leader, heading a dominant party, flaunting a dominant ideology, insisting on unquestioned authority for itself over all citizens – collapsed ingloriously into a heap of a dozen odd states.

The lesson is simple: the mighty Soviet state disintegrated not because citizens had too many rights and too few duties but because it had degenerated into a dysfunctional dictatorship. History also teaches us that such a meltdown is the only denouement that awaits any arrangement of absolute state power over citizens.

Behind Modi’s argument that “too much preoccupation with rights and too little emphasis on duties has weakened India” lies a pining for unaccounted power and unaccountable authority.

Ironically, the rights against which the prime minister spoke are very much part of the constitution – the very document that provides Modi the authority (and even legitimacy) to lord over us.

The Modi crowd is entitled to this retrospective denigration but the rights about which the prime minister wailed are not the gift of a bountiful Nehru-Gandhi dynasty; they are very much hard-wired into the ideology and motivation of our freedom struggle. These rights are not a dispensable flame or marble slab to be doused or moved here and there at the whims and fancies of a monarch.

Admittedly, a strong state is characterised not by the omnipotence of its ruler but by the efficiency and competence of its ruling elites to pursue national glory and prosperity, achieve progress, accomplish goals and generate a stable and just order. A state becomes strong only when its rulers are able to enlist the enthusiastic cooperation of its citizens. Of course, a state can secure compliance and obedience to its dictates at gun point but its presumed strength remains fragile.

It was not all that long ago that an all-powerful monarch, the Shah of Iran, was preening himself before a glittering gathering of rulers from across the world. And then, suddenly, the Pahalvi dynasty was history. The Shah passionately believed that he was pursuing Iranian glory and progress and was presiding over a civilisational renaissance – and he brooked no opposition to his ‘modernisation’ agenda. But the Iranians masses – voiceless and powerless – held back their joyful obedience and defied the emperor at the first break they got.

Reciting an old script

To be fair to Modi, he is not the first from the RSS milieu to quarrel with the constitution and its insistence on accountable governance and an empowered citizenry. From the Jana Sangh’s days, its ideologues have preferred a more authoritative arrangement than is provided for by the Indian constitution (which they snidely referred to as a Nehruvian constitution). Their preference has been for a powerful Centre and weak states; for a strong state and pliant citizens; for the dominance of political authority over civil society; and, for conformity over dissent.

In its second term, the Vajpayee government flirted with the idea of re-arranging the basic constitutional arrangements. It even constituted a high-profile commission to review the working of the constitution. But the Vajpayee regime did not have the courage of its convictions nor the parliamentary numbers to tinker with the basic structure of the constitution. Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s ardour for change got doused by the Gujarat riots of 2002. The ill-advised and ill-designed commission he appointed died an unsung death. But the Sangh’s itch for authoritarian arrangements remains unscratched. As a loyal ideologue, Modi is merely reciting an old script.

Yet, the question remains: why has Modi ginned up this “too many rights and too few duties” bogey now? For seven years, he has enjoyed unquestioned power; neither parliament nor the judiciary have posed any serious hurdle to his imperious impulses and designs, There is no opposition; no JNU; no critical media hauling the regime over the coals for its waywardness; and no Anna Hazare or a JP to romance the Janata.

So why does the prime minister suddenly feel India is weakened? Does he have reason to believe that on his watch India has become vulnerable and weaker? Does he feel the need to manufacture yet another set of enemies for his failures?

Are these the ramblings of a nervous monarch, aware of the gathering discontent in the masses? Or has he fallen victim to the ancient failing of kings and emperors and dictators who confuse their personal glory and vanity with the national wellbeing.

The past seven years have spawned a whole new breed of darbaris who self-servingly believe – in the manner of the old CPSU – that preservation and consolidation of the gains of the Modi Revolution is the only purpose of national life. And, of course, these arrivstes are so busy writing a fake narrative of our times that they have no use for the lessons of history.