Urban Naxals and Red Book: The BJP's efforts to Undermine Rahul Gandhi's Championing of the Marginalised

On November 7, 2024, Maharashtra deputy chief minister Devendra Fadnavis accused Lok Sabha leader of opposition Rahul Gandhi of seeking support from “Urban Naxals and anarchists” during a seminar on the Constitution in Nagpur, pointing out that Gandhi was holding a “red book” in his hand – a pocketbook edition of the Constitution.

This accusation is part of an effort to undermine Gandhi’s consistent framing of his political battle as one to “save the Constitution” from what he sees as the BJP’s encroachments.

Since the last Lok Sabha elections, Gandhi has worked to emphasise this constitutional defence, positioning himself as a leader committed to upholding the values enshrined in the Indian republic. Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi's leadership, the Constitution has been repeatedly disregarded in pursuit of a majoritarian agenda that aligns with Hindutva ideals.

Since the last Lok Sabha elections, Gandhi has worked to emphasise this constitutional defence, positioning himself as a leader committed to upholding the values enshrined in the Indian republic. Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi's leadership, the Constitution has been repeatedly disregarded in pursuit of a majoritarian agenda that aligns with Hindutva ideals.

Gandhi’s transformation, especially evident through his Bharat Jodo and Nyaya Yatras, has shifted him from being seen as a “me too Hindu” simpleton to a champion of marginalised groups. This rebranding has positioned him as a significant challenge to the BJP with his unorthodox approach to leadership.

Although Gandhi’s campaign for social justice has yet to translate into electoral success, it holds considerable potential to disrupt the BJP’s dominance and transform Indian politics in ways that are unprecedented. Fadnavis’s pointed remark against Gandhi reveals a sense of urgency and defensiveness within the Hindutva camp as it confronts the possibility of a growing counter-narrative that champions constitutional values and social equity.

Dissenters as Urban Naxal

The oxymoron Urban Naxal gained mainstream attention in the 2010s after a spate of arrests of activists such as Arun Fereira, Prof. G N Saibaba and others as Maoist functionaries.

However, the references to leftist influences in urban areas and their link to Naxalism can be found in security and policy analyses from as early as the 1990s and 2000s.

The police projected to the gullible people that they had uncovered the Maoists’ plot to build urban network and busted it by arresting these activists. As a matter of fact, these documents containing aspirational plans of Maoists (strategy and tactic) were freely floating on the net for decades (which may still be available on many clandestine proxy sites) and the activists named as Urban Naxals stand exonerated after years of unjust incarceration by the courts, nailing the police lie.

However, the political narrative is built on this falsehood for justifying arrests of anyone who raised voice against the government on behalf of people as Urban Naxal.

The term was popularised by one Bollywood aspirant, Vivek Agnihotri, in his 2018 book by that title Urban Naxals: The Making of Buddha in a Traffic Jam.

Based on the police inputs, the book amplified the fear psychosis already created by the statements such as Naxalism was the "greatest internal security threat to our country" made by the then prime minister Manmohan Singh in 2009.

The term has been used to describe individuals who, according to some, use their positions in urban centres (media, universities, NGOs) to spread or support Naxalite ideology covertly. It named campuses such as Jawaharlal Nehru University, Hyderabad Central University, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Allahabad University, IIT Madras, Jadavpur University as the citadels of urban Naxalism.

The likes of Kanhaiya Kumar who had come in limelight due to the fake narrative constructed around the students’ meet on the anniversary of Afzal Guru’s hanging were branded as Urban Naxals.

Agnihotri, later would produce third class films such as The Kashmir Files, with similar fake narrative against Islam, which would be openly canvassed by none other than Narendra Modi.

The anti-Islam/Muslim rhetoric has been the main weapon in the arsenal of Sangh Parivar to consolidate Hindus for gaining power through electoral process and the "Urban Naxal" has been a sinister addition to it to eliminate dissent in order to preserve power.

Constitution as a 'red book'

Fadnavis’s tactic of linking the red cover of a seminar notebook to a supposed “Naxal connection” while accusing the Congress of undermining the Constitution reflects a familiar BJP strategy: accusing others of the very misdeeds it practices. While Fadnavis accuses the Congress of subverting the Constitution by misconstruing a blank notebook designed with a cover resembling the Constitution, it is the BJP that has often faced criticism for undermining constitutional principles.

This paradox is underscored by the well-documented history of the RSS’s resistance to the symbols and values of post-independence India, including its aversion to the national flag, the national anthem, and the Constitution.

The RSS’s publication, Organiser, vociferously opposed the adoption of the Tricolour as the national flag. In an editorial titled “National Flag”, published after the Constituent Assembly’s decision on July 22, 1947, the Organiser stated, “The people who have come to power by the kick of fate may give in our hands the Tricolour but it [will] never be respected and owned by Hindus. The word three is in itself an evil, and a flag having three colours will certainly produce a very bad psychological effect and is injurious to a country.”

Similarly, in Bunch of Thoughts, Golwalkar expressed disdain for the tricolour, describing it as emblematic of an intellectual void.

The Sangh's opposition persisted until 2001, when Rashtrapremi Yuwa Dal activists, led by Baba Mendhe, forced the RSS to address its position by hoisting the national flag at its Nagpur headquarters on Republic Day, challenging the organisation’s history of not displaying the tricolour.

Though the activists were arrested and later acquitted after 11 years, the incident sparked widespread controversy and was raised in Parliament. Following the establishment of the Indian Flag Code in 2002, the RSS raised the national flag at its headquarters on Republic Day for the first time in 52 years.

The RSS’s initial disapproval of the Constitution was also evident. The organisation criticised it for omitting references to Hindu texts such as the Manusmriti. In a November 30, 1949 in its editorial, Organiser stated, “But in our constitution, there is no mention of that unique constitutional development in ancient Bharat... To this day his laws as enunciated in the Manusmriti excite the admiration of the world and elicit spontaneous obedience and conformity. But to our constitutional pundits that means nothing.”

This stance underscored a preference for a governance model rooted in Hindu traditional law, which stood in stark contrast to Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s vision of a secular and egalitarian society aimed at eliminating caste-based discrimination.

Consistent with this history, the RSS continues to hint at changing the Constitution. Despite its projection of nationalistic fervour, it views the Constitution’s liberal principles of social justice, secularism, and federalism with skepticism. Fadnavis’s depiction of the pocket Constitution as a “red book” evokes imagery of Mao’s Red Book from the 1960s, implying a subversive, anti-establishment ideology and playing into a narrative that positions dissent as a threat to national unity.

Rahul’s disruptive politics unsettling the BJP

Rahul Gandhi’s recent political approach represents a notable shift, positioning him as a leader who prioritises issues of inequality and social justice. This evolution has unsettled political opponents, particularly within the ruling BJP camp. By addressing economic disparities, social exclusion, and the empowerment of marginalised communities, Gandhi has aimed to connect with a wider audience that feels neglected by development models focused predominantly on economic growth.

The insinuation of his association with “Urban Naxals” aligns with efforts to delegitimise dissent or progressive discourse by linking them to anti-state elements. Such framing deflects public attention from the substantive issues being raised and redirects it towards defending national or societal integrity against perceived threats.

The Modi-led BJP has solidified its political base through nationalist rhetoric, cultural conservatism, and religious identity politics. Yet, the emergence of a pro-people narrative emphasising economic inequality and social justice poses a challenge to this model by appealing directly to voters’ lived realities and aspirations. Gandhi’s strategy harks back to themes of pro-poor policies that were influential in Indian politics under leaders such as Indira Gandhi.

Positioning social justice as a core principle, Rahul Gandhi’s strategy has the potential to create unity across religious and caste divides, fostering a counter-narrative to the BJP’s communal and polarising politics. This could refocus public discourse from identity-based tensions to class-oriented discussions, which may resonate in an era marked by growing economic disparity.

The appeal of Gandhi’s evolving vision lies in shifting attention from religious and cultural divides to concerns about economic inequality, unemployment, farmers’ rights, and social justice. This approach has the potential to forge alliances that transcend traditional political boundaries.

If successful, Gandhi’s pro-people, inclusive narrative could erode some of the BJP’s conventional strategies, which often depend on consolidating support through communal and identity-driven appeals. The portrayal of mainstream leaders like him as “Urban Naxals” serves as a tactic to blur the lines between legitimate democratic dissent and extremist ideology.

This strategy aims to neutralise an emerging response to communal politics by framing it as a security concern, thereby undermining the credibility of Gandhi’s message and stalling momentum for an alternative political discourse.

The obstacles within

The main obstacle to Rahul Gandhi’s political resurgence is not so much the BJP, but the Congress Party itself. While Gandhi has repositioned himself effectively, projecting an image of empathy and commitment to socio-economic issues that resonate with segments disillusioned by the BJP, this personal transformation has not translated into an organisational shift.

A critical challenge remains the entrenched power of the Congress’s old guard – leaders who are risk-averse and adhere to traditional strategies. Their “business as usual” approach fails to counter the BJP’s aggressive, modern, and media-savvy campaigns. This hesitance to adopt bold, innovative strategies prevents the Congress from matching the energy and outreach that have become hallmarks of BJP’s political machinery.

For the Congress to become a credible alternative, it requires an organizational overhaul. It must prioritise at least three things immediately.

Firstly focusing on a younger Leadership and Empowering a new generation of leaders capable of mobilising the party at the grassroots and appealing to a younger, more diverse voter base.

Strategic Cohesion is the second area where the party needs to establish a clear, unified stance on key issues to move beyond ambiguous positions that have historically caused voter confusion and apathy. It must pose an alternative vision to BJP’s communal one.

Lastly, a local connect is important to strengthen state and local party units to fight regional battles with tailored strategies to challenge the BJP’s state-by-state dominance.

If the Congress continues to rely on outdated methods, such as elite alliances and conventional electoral tactics, it risks being perceived as stagnant and disconnected. This is particularly problematic when facing a dynamic BJP that continuously reinvents its strategies. Without channelling Gandhi’s revitalised image and vision into coherent, organizational momentum, the Congress will struggle to pose an effective challenge to the BJP.

Posters with Fadnavis brandishing a gun

In the recent past, posters of Devendra Fadnavis brandishing a gun have surfaced after police encounters in Maharashtra. Even though the BJP has distanced itself from the posters, this strategy aims to project decisiveness and strong governance by championing a hardline stance on crime.

This narrative can resonate with voters frustrated by the slow judicial system and eager for swift action against serious offenders like rapists or drug traffickers.

The image of Fadnavis as a crime-fighting crusader is designed to appeal to the public’s desire for security and a forceful response to crime. However, the BJP’s history in Maharashtra complicates this narrative.

The party’s role in destabilising alliances and engineering political splits, particularly with the Shiv Sena and NCP, has earned it a reputation as a “breaker of parties.” This background may lead some Maharashtrians to view Fadnavis’s displays of force with skepticism, seeing them as potential electioneering rather than genuine commitments to public safety and justice.

Maharashtra’s political culture values leaders who combine assertiveness with justice and due process. While hardline tactics can attract support, voters also respect the rule of law. If Fadnavis’s image is seen as undermining these principles or promoting vigilante-style justice, it could backfire, especially among moderate and progressive segments.

The timing of the posters comes as the BJP seeks to repair its image following accusations of engineering political disruptions. Whether this aggressive posturing will recast the BJP as protectors of public order or reinforce its reputation for opportunism depends on the public’s perception. If seen as performative or politically expedient, it risks alienating voters who value justice as more than displays of force.

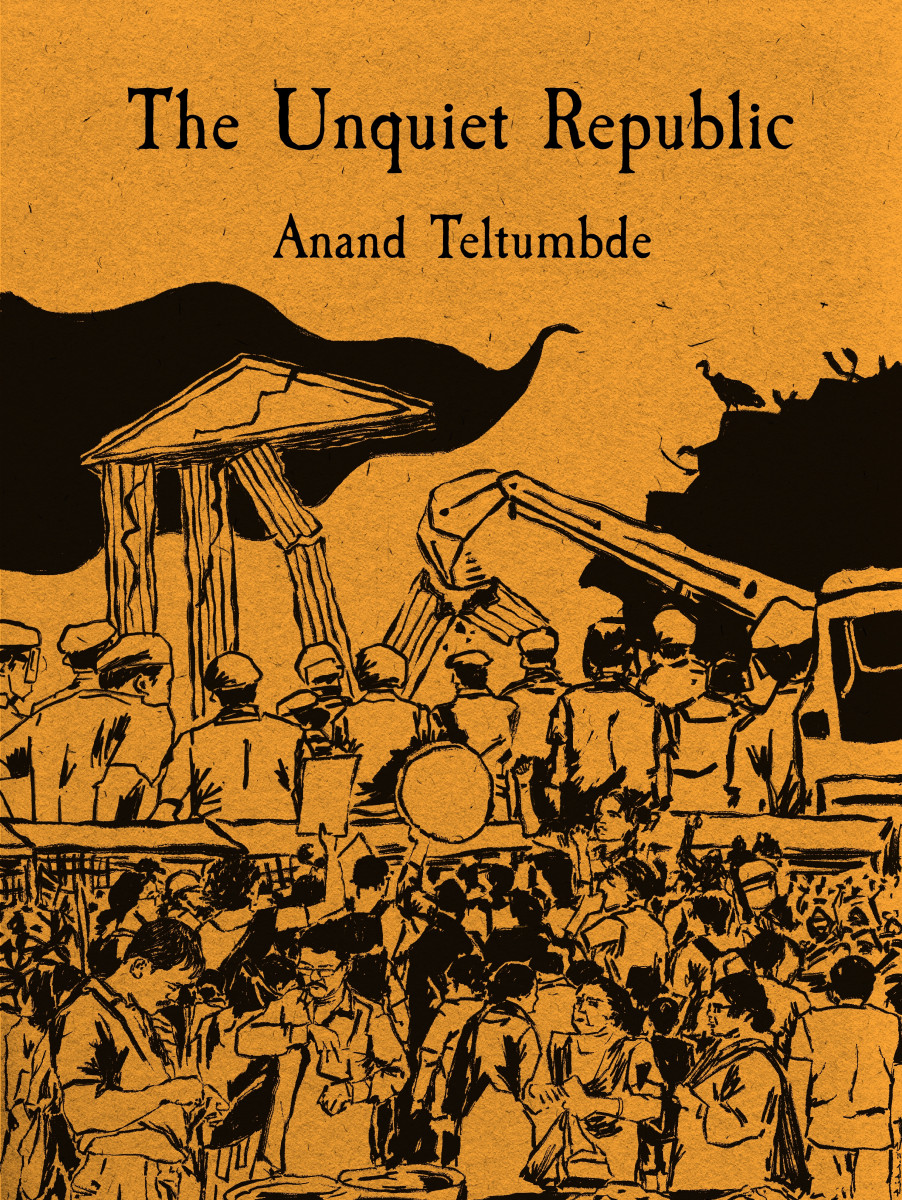

Anand Teltumbde is former CEO, PIL, professor, IIT Kharagpur and GIM, Goa; writer and civil rights activist.

The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.