Representation of Women in Politics: Congress's UP Move Is a Step in the Right Direction

Uttar Pradesh, the Northern heartland, may now be best known for its less-than-democratic governance and underwhelming gender equality. But it was also the home of India's first female chief minister, Sucheta Kripalani (1963-67), who was also UP's labour and industries minister, a multiple-time member of parliament, a general secretary of the Congress who initiated the party's women's wing. Kripalani faced no dearth of sexism, corruption and goondaism in Uttar Pradesh.

Many decades have passed since, but it is as if time has stood still in the state.

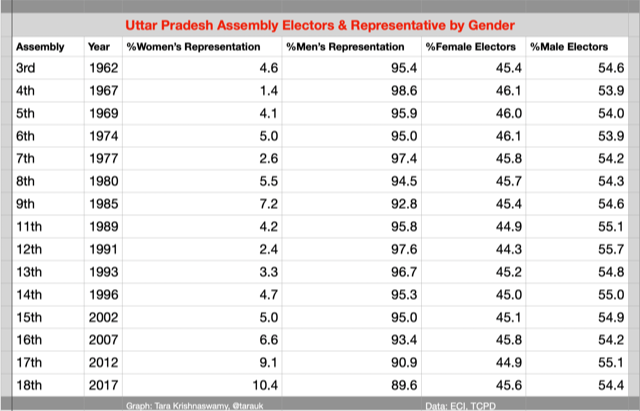

In election after election until 2017, men accounted for more than 90% of MLAs that were sent the assembly. The current assembly was the first to have a double-digit percentage (10%) of female MLAs. So far, the average has hovered around an abysmal 5%. The table below shows the near-complete absence of women in state-level legislation and policymaking.

Representation of women and men in Uttar Pradesh. Photo: Author provided

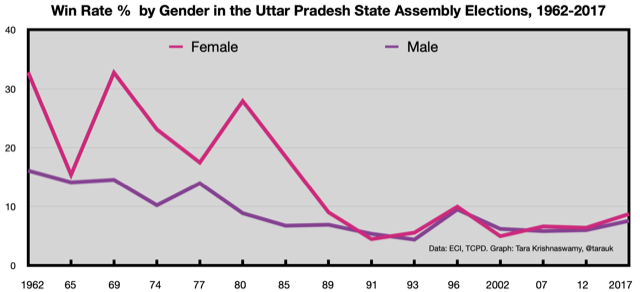

An oft-repeated cliche is that women are not 'winnable candidates' in a patriarchal society. However, win rate percentages do not bear that out. Male and female win rates are either comparable or largely favourable towards the latter.

Win rates of men and women candidates. Photo: Author provided

The root cause for the dismal representation of women lies with the political parties. In their attempts to capture power, parties try every combination to consolidate the electorate. However, each of these considerations – caste, religion, rural, urban, ideology, landed, elite, subaltern, seat-sharing – has resulted in almost exclusively male contestants and winners. The ballot has been far out of the reach of politically aspirational women in UP.

This also implies that one half of the electorate has had little to no say in state policy and budgeting, the two most crucial factors driving – or hindering – human development.

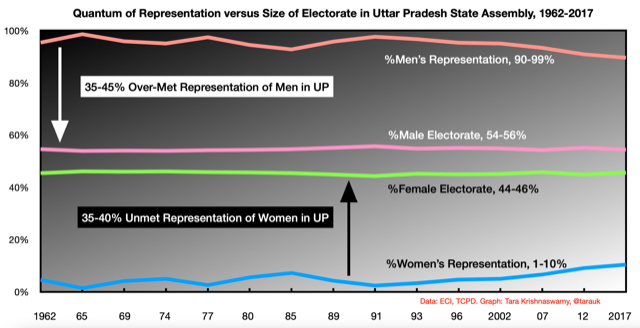

The graph below shows the overrepresentation of males in the UP assembly – ranging between 90-99%, over and above their share of the electorate, which is 53-55%. Proportionally, there should be more than 180 women in the 403 seat assembly. There have only been between 6-42!

Photo: Author provided

It seems the only two abiding features of post-independence UP politics are the over-representation of men in politics and poor HDI and governance outcomes, exacerbated by criminality. Whether these outcomes are causal or correlated is not the point of discussion. But it is clear that the myriad contortions of caste configuration, religious polarisation and tactical and ideological coalitions produce a male-dominated ballot and suboptimal governance.

Also Read: Female Parliamentarians at a Historic High, but Parties Must Do More

The Congress's move

In this context, the Congress's decision to reserve 40% of the seats for women in the 2022 UP assembly elections is entirely laudable. Priyanka Gandhi Vadra's announcement has thrown up an array of reactions. Some have noted that giving tickets to women does not equal empowerment. Others have pointed out that the Congress is not a major player in UP. Will the same policy be implemented in other states, ask some, while even others wonder what will happen if the party forms a coalition.

These criticisms and observations are all but academic. They question universality, elasticity and negotiability in what is a campaign gambit. The Congress's announcement must be seen for what it is: a poll bugle. A major national party has promised to field at least 40% female candidates in the assembly elections for the country's largest state in terms of population. This is a first.

It is also a casting call. The Congress, which is a smaller player, is trying to recruit new candidates who will be drawn from an under-represented demographic. This is a clever move and a pressure tactic too. The Congress's decision can put the other parties on the mat if the media interrogates other parties on gender-equitable allocation of tickets. Indeed, the move also puts the Congress's state units elsewhere under the same pressure.

Beyond that, it is also a missive to the female electorate that they are eligible for a stake in the annals of state power if they embrace the Congress platform. Of course, there are no guarantees of victory; there never are.

Finally, and most crucially, it is the next step in a silent electoral crusade that began with Mamata Banerjee's Trinamool Congress in 2014. The party fielded 35% female candidates then and followed it up with 41% in 2019. Peer pressure caused even the Left combine and the BJP to field more women in West Bengal. In Odisha, Naveen Patnaik's a third of Biju Janata Dal's candidates for the 17th Lok Sabha were women.

Subsequently, the 2020 Bihar elections saw a historic 19% women candidates put up by Nitish Kumar of the Janata Dal (United). The Congress's announcement should be seen as a continuation of this movement.

Congress general secretary Priyanka Gandhi Vadra with party members pose for a photo at the party office in Lucknow, October 19, 2021. Photo: PTI/Nand Kumar

All this did not happen at once. It has been slowly cooking for seven years, and there is a long road ahead yet. Still, the pattern is not able. Big players, who regularly employ caste coalitions and religious polarisation to mobilise voters, are now also focussing on putting up more female candidates.

The 73rd and 74th Amendments to the constitution liberated local governments from male clutches in one fell swoop. But most change is the painful turning of the wheel. The percentage of women candidates has been stagnant for decades. That is slowly changing. However, it must be noted that without commitment to fair and equitable candidature, increased representation on the ballot is insufficient for a representative assembly.

And it needs to be reiterated that the representation of women on the ballot is no guarantee of victory; that is up to voters. However, appearing on the ballot at least gives them the chance to enter the assembly. It would be prudent to remind ourselves that in most instances, revolution is a process, not an event. And that is why for UP's beleaguered politics, the Congress's 40% reservation for women provides the hope that its future can be female.

Tara Krishnaswamy is a co-founder of Shakti – Political Power to Women, a non-partisan citizen’s collective with the goal of increasing women’s representation in parliament and state assemblies.

This article went live on October twenty-second, two thousand twenty one, at zero minutes past four in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.