Non-Violence and the Elusiveness of Its Ascending and Descending Notes

Gandhi’s formulation of ahimsa is often seen through the prism of his non-cooperation and satyagraha campaigns during India’s movement for freedom. Inevitably, the unfolding of ahimsa as a concept, and as a religion for Gandhi, gets clouded by the urgency to gauge the efficacy of non-violence. In reality, Gandhi’s conceptualisation of ahimsa has an ascending and descending scale. It is a bit like the raga in Indian musical traditions. A raga has an ascending and descending scale, but it is a complete entity in itself, with special characteristic marks of identification, modes of treatment and distinctiveness of notes. Such, too, is Gandhi’s ahimsa. It has two distinctive registers but neither is the whole. In the ascending sense of ahimsa, the stress falls on non-violent action and violent and non-violent actors. The descending range withdraws from the world of people, giving ahimsa an inward quality. In neither is the overall integrity of the idea lost. It lies in Gandhi’s fidelity to moksha, desireless action, the futility of the body and the centrality of death. And all of these elements are inseparable from establishing ahimsa as a fundamental principle of Hinduism.

Writing a piece in August 1920 about their divergent understanding of religious texts and terms in response to Narayan Chandavarkar, Gandhi defines ahimsa in a way that appears to be a perfect illustration of the ascending tenor of ahimsa. It is peopled by believers in ahimsa as also evil-doers, but also ideas of creation, destruction and love. There are agents and agency, and the Creator remains a ubiquitous presence.

I still believe that man not having been given the power of creation does not possess the right of destroying the meanest creature that lives. The prerogative of destruction belongs solely to the creator of all that lives. I accept the interpretation of ahimsa, namely, that it is not merely a negative state of harmlessness but it is a positive state of love, of doing good even to the evil doer. But it does not mean helping the evil-doer to continue the wrong or tolerating it by passive acquiescence—on the contrary, love, the active state of ahimsa, requires you to resist the wrong-doer by dissociating yourself from him even though it may offend him or injure him physically.

As a first step, he advocates the practice of ahimsa in relation to neighbours and associates. It ought to remain a great and active force in every moment of our lives, and must guide every single thought and action. But with hatred and ill-will in the heart, non-violence, he warns, will remain a non-starter. Non-violence is not meek submission to a tyrant. It is conscious suffering by putting ‘one’s whole soul against the will of the tyrant’. The conquest of physical strength by spiritual strength is seen in the example of Lord Rama. Surrounded by insolent might on all sides, he took on the ten-headed Ravana.

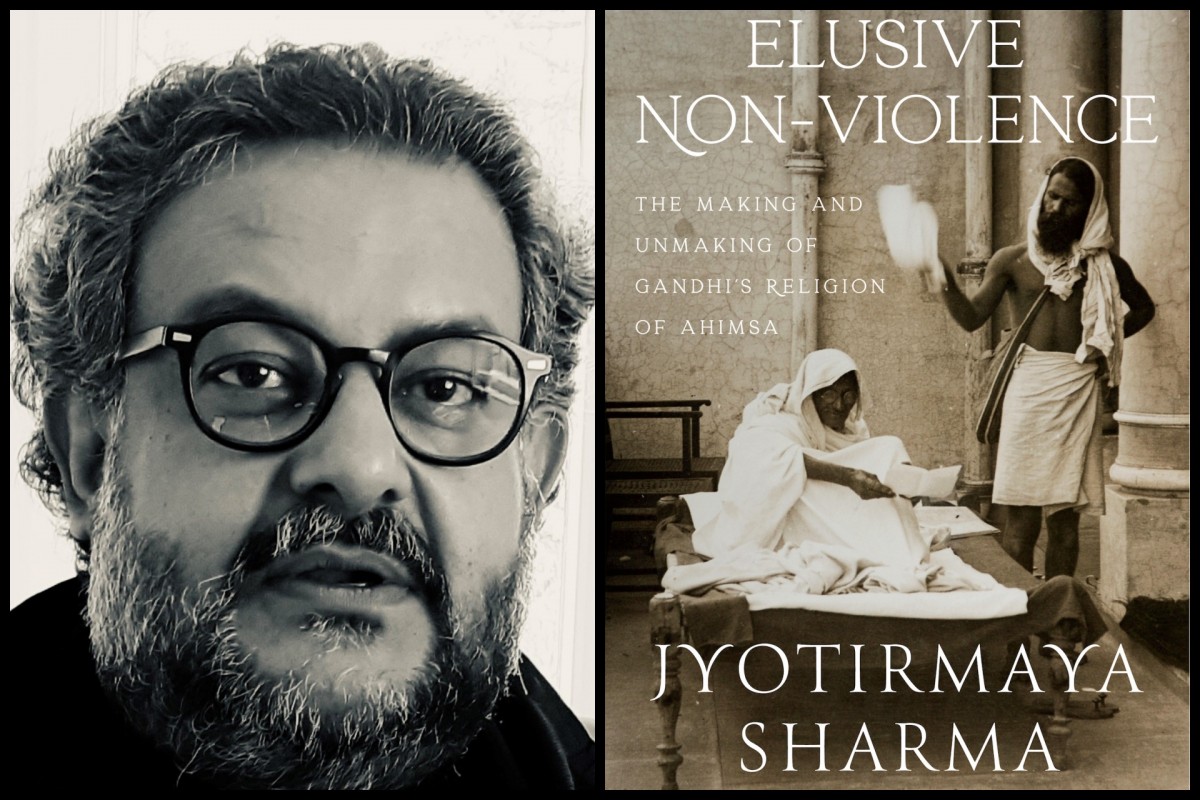

Jyotirmaya Sharma (left); Cover of Elusive Non-Violence: The Making and Unmaking of Gandhi's Religion of Ahimsa (Context, 2021) (right)

In an illustration of ahimsa’s descending note, death resurfaces as the final arbiter of all things. Ahimsa and freedom from the fear of death, in tandem, move a person closer to realising the self or the atman.

Just as one must learn the art of killing in the training for violence, so one must learn the art of dying in the training for non-violence. Violence does not mean emancipation from fear, but discovering the means of combating the cause of fear. Non-violence, on the other hand, has no cause for fear. The votary of non-violence has to cultivate the capacity for sacrifice of the highest type in order to be free from fear. He reckons not if he should lose his land, his wealth, his life. He who has not overcome all fear cannot practise to perfection. The votary of ahimsa has only one fear, that is of God. He who seeks refuge in God ought to have a glimpse of the atman that transcends the body; and the moment one has a glimpse of the Imperishable atman one sheds the love of the perishable body. Training in non-violence is thus diametrically opposed to training in violence. Violence is needed for the protection of things external, non-violence is needed for the protection of the atman, for the protection of one’s honour.

As a first step, he advocates the practice of ahimsa in relation to neighbours and associates. It ought to remain a great and active force in every moment of our lives, and must guide every single thought and action. But with hatred and ill-will in the heart, non-violence, he warns, will remain a non-starter. Non-violence is not meek submission to a tyrant. It is conscious suffering by putting ‘one’s whole soul against the will of the tyrant’. The conquest of physical strength by spiritual strength is seen in the example of Lord Rama. Surrounded by insolent might on all sides, he took on the ten-headed Ravana.

He counts his fast unto death as a final seal on his faith in non-violence. Sacrifice of the self is the ultimate weapon in the hands of a non-violent individual. The shastras speak of people who fasted for their prayers to be heard. Sometimes God would hear their entreaties, but at other times, would remain silent. Yet, these people continued to fast, and died quietly and unsung. Despite an unresponsive God, they retained their faith in God and in non-violence. All that is pure and good in the world, Gandhi believes, is because of the death of scores of these unknown heroes and heroines.

There are moments, however, when both the ascending and descending notes of Gandhi’s religion of ahimsa come together. Even in such cases, it is evident that the descending scale is dominant.

This non-violence cannot be learnt by staying at home. It needs enterprise. In order to test ourselves we should learn to dare danger and death, mortify the flesh and acquire the capacity to endure all manner of hardships. He who trembles or takes to his heels the moment he sees two people fighting is not non-violent, but a coward. A non-violent person will lay down his life in preventing such quarrels. The bravery of the non-violent is vastly superior to that of the violent. The badge of the violent is his weapon—spear, or sword, or rifle. God is the shield of the non-violent.

This extreme call to courage and courtship of death left many of Gandhi’s interlocutors bewildered. For them, to fear, to have attachments and to treasure life was just ordinarily human. In a conversation, B.G. Kher tells him of a world made of opposites. Fear and courage exist side by side. Moreover, fear is nothing to despise or resent. Gandhi responds that fear might have its uses but cowardice has none, reminding him of the Gita’s message to transcend opposites. What is evident is that both men are talking about the pair of opposites in entirely different ways. Kher does not pit fear against courage but talks of their coexistence. Gandhi pits fear against cowardice and speaks of forcing a moral choice.

Gandhi chose a particular definition of Hinduism. In doing so, he claimed its universal authenticity and validity. He rejected popular forms of Hinduism as much as he selectively borrowed from the shastric tradition. In recognising the affinity between order and violence, he rejected punishment as a part of order and aimed to constitute order as duty. In turn, duty could only be enforced if there was action. But action inevitably carries the taint of violence. The only perfect way to escape violence is to let the vehicle of violence, the body, perish. In this way, humans would achieve desireless action and gradually move towards the ultimate aim of moksha. Even non-cooperation is, in the end, an act of self-sacrifice. Therefore, to meet one’s death without striking a blow, he asserts, is fulfilling one’s duty in the extreme, so long as one leaves the result in God’s hands.

Someone writes to Gandhi in 1928 asking if it is not impractical to set forth ahimsa as the highest religious ideal and code of conduct for humans, knowing that it is impossible for anyone to fulfil it. Gandhi’s answer is comprehensive and complete. The very virtue of a religious ideal, he says, is that it cannot be entirely realised in the flesh. The proof of any religious ideal must lie in faith. But faith is impossible if perfection can, indeed, be realised while surrounded by all that is subject to decay. The spirit’s essential nature is expansion; it has no scope to do so in the midst of the transitory physical world. The body and the spirit are two different entities: ‘Where would be room for that constant striving, that ceaseless quest after the ideal that is the basis of all spiritual progress, if mortals could reach the perfect state while still in the body?’ If easy perfection while retaining the body were possible, humans would have a model for all to follow. There would be no plurality or diversity of religions as everyone would follow the same ideal of perfection.

What is the nature of an ideal? It is boundlessness, says Gandhi. And if it is boundlessness, religious ideals must remain unattainable by imperfect human beings. But they are still closer to us than our bodies because they represent truth and reality. Faith in one’s ideals, then, is true life: ‘[I]t is man’s all in all.’ If there is violence all around, that individual is fortunate who can understand the laws of ahimsa, even in such a situation. What does he comprehend? He intensely longs for ‘deliverance from the bondage of flesh which is the vehicle of himsa’. It is a state that the sages saw only in a trance and the poets found difficult to articulate.

[A] state in which the will to live is completely overcome by the ever active desire to realize the ideal of ahimsa and all attachment to the body ceasing man is freed from the further necessity of possessing an earthly tabernacle.

Gandhi calls this a ‘consummation’. As long as it is not achieved, violence will continue to claim its due. And as long as the body remains, ‘a man must go on paying the toll of himsa’. After all, the ideal is all.

Excerpted with permission from Elusive Non-Violence: The Making and Unmaking of Gandhi’s Religion of Ahimsa by Jyotirmaya Sharma, published by Context, October 2021.

This article went live on October second, two thousand twenty one, at fifty-nine minutes past three in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.