Review: Misconceptions Over Instant Triple Talaq Persist

The Supreme Court's verdict on August 22, 2017, invalidating instant triple divorce and the resultant furore has prompted Ziya Us Salam to look deeper into the issue. He has looked into instances of women having undergone sufferings since the 1970s, illustrating with many other examples, besides going into personal details of the seven women petitioners – how these women kept their spirit and forbearance intact and went up to the Supreme Court braving tremendous odds, and examining their sufferings in the light of the Quran, to be read and understood along with the socio-historical underpinnings.

This is unlike the Urdu memoir, Kaarwaan-e-Zindagi, of Maulana Abul Hasan (Ali Miyan) Nadvi (1914-99). In its third volume, chapter four, the Maulana discusses in detail as to how the All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB) in February 1986, under his stewardship, influenced the then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi to nullify the Supreme Court verdict on Shah Bano through legislation. He, however, chooses not to say a word about the un-Quranic talaq-e-biddat which was first pronounced against Shah Bano (1916-92) inside the Indore court in November 1978, before the judge, only after the judge remarked that even under the Personal Law, Shah Bano was entitled for a maintenance from her well-to-do advocate husband. It was this un-Quranic divorce that was invalidated by the Supreme Court. Shah Bano’s sufferings in her 70s are conspicuously missing from Ali Miyan’s long narrations. So is his unjustifiable silence on the un-Quranic divorce. Unlike Shah Bano, most of these petitioners are in the prime of their life and career.

Ali Miyan records that he pointed out to Rajiv Gandhi that provincial Waqf Boards should be entrusted with the task of maintaining the divorced woman if she did not have relatives to take care of her. But the triumphant Ali Miyan, after 1986, never checked if his proposal was really workable for Shah Bano, whose victory in the Supreme Court was nullified admittedly through manipulative tricks by these people. The Maulana is, however, honest in admitting that such a trick turned out to be counter-productive in the sense that it fuelled majoritarian communal reaction.

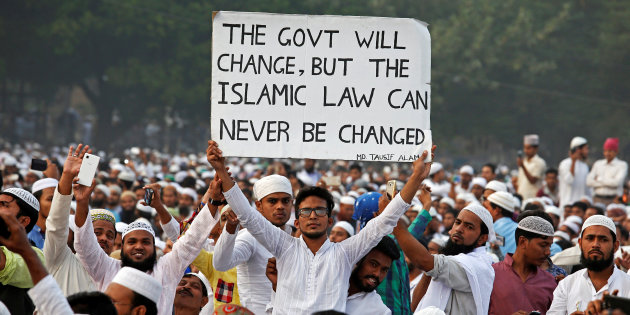

A man holds a banner during a rally organised by All India Muslim Personal Law Board in Kolkata. The board has not enough to protect Quranically-guaranteed interests of the women. Credit: Reuter Files/Rupak De Chowdhuri

Ziya Us Salam seems agonised by the fact that there are several misconceptions over instant triple talaq not only at the popular level but also among informed segments, resulting in misinformation and wilful disinformation. This book is an "exercise of clearing the air around the issue of divorce in Islam...to present a complete picture with the help of the Quran and back it up with instances from the Hadith and history" (p. Xxiii). Like Shah Bano, the dilemmas and agonies of most of the petitioners persist. The judgement does not talk of maintenance or alimony. If instant triple divorce is void, then can a woman re-marry her husband having passed her iddat long back? Or should she go for khula if she chooses to marry someone else? There are more questions than answers in their lives. Yet, the AIMPLB refuses to delve into the issues threadbare. Their street agitations seem to vilify the sufferings of these women rather than criminalise the men who resort to un-Quranic divorce. Misogyny persists!

Brief chapters dealing with specific aspects in this slim volume are organised in a coherent manner. The book looks into almost every dimension of the issue – theological, socio-historical aspects, intricacies and nuances – purporting to help common men and women see through the misconceptions. He has assailed the Urdu (and other vernacular) media and sections of the Muslim intelligentsia, including legal academics and columnists, who have not made enough interventions in these spaces. The Urdu media, which has the largest reach in the communities of theological seminaries, often does not offer space for contending debates on such issues. According to him, the un-Quranic talaq-e-biddat became acceptable because not enough interventions have been made to educate the common people. Looking into various court verdicts, he arrives at the conclusion that "no judgement of the Supreme Court has gone against the Quran (p. 210)."

Selective Amnesia

Citing relevant verses from the Quran, the book dwells upon the long process of ending a genuinely unhappy marriage, to be preceded by arbitration and reconciliation efforts. "Nowhere does the Quran refer to instant triple talaq or approve of it even indirectly" (p. 16). The parting has to happen, "on fair terms...the husband does not enjoy an unbridled right to divorce". In a certain contingent situation, Caliph Umar made instant triple talaq valid but the man had to be flogged. Subsequently, Caliph Ali had invalidated instant triple talaq. These two vital aspects of the issue are generally kept unknown from the common people. Interestingly, Caliph Umar did penalise instant triple divorce, yet there was a lot of opposition when the incumbent majoritarian right wing government proposed a Bill to criminalise instant triple divorce, something the clergy ought to have done at least in 1986, if not earlier.

Except the Hanafi, almost no other sect and sub-sect validates talaq-e-biddat. The author argues that there are some Hanafi jurists who even invalidate instant triple divorce (p.45), and that "there is no direct word from Imam Hanifa on triple talaq’ (p. 46). The author argues strongly against halala as there is absolutely no Quranic sanction for the way it is practised in parts of India. Despite the petitioners’ pleas, the Supreme Court has not delivered its verdict on halala, polygamy, custody of children, maintenance, etc.

Ziya Us Salam, Till Talaq Do Us Part: Understanding Talaq, Triple Talaq and Khula. Penguin, Delhi, 2018. Pages xxvi+218, Price INR 399/-ISBN 9780143442509.

Similarly, the author also clears the ignorance and/or misconceptions about khula, which, he says, is a woman’s ‘inalienable right to divorce’ and ‘the husband cannot refuse consent’ (p. 76).

Ziya us Salam talks of talaq-e-tafweez, under which the husband vests in his wife the right to divorce him. This condition should ideally be written down at the time of marriage in the nikahnama and can go a long way in bringing down the rate of divorce. Sadly, there is hardly any nikahnama that is framed in such a manner so as to include this condition of divorce’ (p. 80). While going for its 26th plenary at Hyderabad in early February 2018, the AIMPLB announced that the session would prepare a model nikahnama but reneged on it. Faizan Mustafa’s foreword to the book under review emphasises that the government should make a nikahnama that compulsory stipulates a complete ban on instant triple divorce (p. Xii).

Patriarchic Hold Over Quranic and Historical Interpretations

In this context, one must recall Sakina (born 671 AD), daughter of Husain, and great granddaughter of the Prophet. Sakina, in her marriage contracts, stipulated that she would not obey her husband but would do as she pleased, and she did not acknowledge that her husband had the right to practice polygyny, says Fatima Mernissi (1940-2015), in her well-researched book Women and Islam (1990). Also, there are some instances of such nikahnamas in 17th century India during the Mughal rule. "Around fifteen years ago, the AIMPLB had promised to draft a model nikahnama. Unfortunately the wait is still on", complains Ziya Us Salam. Mernissi, therefore, underlines, "if women's rights are a problem for some modern Muslim men, it is neither because of the Koran nor the Prophet, nor the Islamic tradition, but simply because those rights conflict with the interests of a male elite".

The author says that the AIMPLB "obfuscates and oscillates" for which he puts greater blame on the politically-affiliated non-clergy members of the Board, whereas the fact is that the clergy too are politically affiliated and they too enjoy the privilege of being nominated to legislative houses. He says that only necessary reforms “will decide whether the AIMPLB becomes an upholder of justice and fair play, or whether it is reduced to just another NGO using religion to serve its ends. The ball, at the moment, is in the board’s court. Time is ticking”, he warns (p. 170).

The AIMPLB chose to become a respondent and then pledged in the Supreme Court to start a public movement against instant triple divorce. Instead, it launched a massive campaign, bringing out women on the streets, against the Bill to criminalise instant triple divorce. True, there are many flaws and limitations in the proposed Bill, but the board was not issuing its own draft Bill. They were simply misleading women, instigating them to say ‘No’ to state interference in Personal Laws. Thus, the board was not doing enough to protect the Quranically-guaranteed interests of women in a patriarchical society, says Ziya Us Salam. Historically speaking, there is hardly any instance where socio-religious reforms have succeeded without state support.

Maintenance to the Divorced Women

The volume under review, however, leaves out the issue of maintenance/alimony. This is too crucial an issue to have been left out. In Surah Baqrah’s verse 236 and 241, much has been ordained for even such a divorced woman who has not been touched by her husband, and to whom he is not even liable to pay Mahr (roughly translated as dower). The word Mutah (parting gift) is basically a settlement. Whether it has to be paid as alimony, i.e., regular maintenance till she dies or remarries or as a share in the wealth and property of the man, is best left to fair practice, judicial tenability and the mutual agreement of the parties.

This slim, lucid volume is a timely intervention which will hopefully succeed in its objective of clearing many misconceptions about the issue that has seen wide disjunction between the scriptures and practice. For this to actualise, the book's vernacular renderings would be even more helpful.

Mohammad Sajjad is a professor at the Centre of Advanced Study in History, Aligarh Muslim University, and author of Muslim Politics in Bihar:Changing Contours.

This article went live on March twenty-ninth, two thousand eighteen, at thirty minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.