Can We Talk About Refugees Without Discussing the Politics of Becoming One?

June 20 is celebrated internationally as World Refugee Day. This year, with the fast escalating immigration crisis in the US, displaced peoples’ issues dominated the news cycle.

In times of increasing awareness of (and sometimes, resistance to) the crisis, efforts are being made by several humanitarian agencies and activists to humanise the forcibly othered refugee. One such effort was the recent TEDx Talk held inside the Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya in collaboration with the UN’s refugee agency, United High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). It was hailed as the “first TEDx event hosted in a refugee camp, with refugees, and also for refugees”.

The potential of this event was enormous in broadcasting a different reality to the world, with refugees being given the chance to construct their own narrative outside of ones assigned to them. But can organisations like TED, which focus solely on the individual in general, work just as well as a platform in a politically charged atmosphere? In a refugee camp, will it do more harm than help?

Can change be affected if there is no focus on the underlying, structural causes of refugeehood? Can the TEDx Talks be separated from the politics of the camp, and would there be tangible differences made if there is no engagement with the latter?

It is always possible to both champion the individual and contextualise them within their political situation. Refugees can be, and are, agents of change despite their circumstances, but to avoid creating more displaced people, talks of empowerment need to be framed in the political reasons behind their refugee status.

Resilience as enough

TEDxKakuma Camp’s central theme of ‘thrive’ hoped to present that “empowered refugees can shape a peaceful and tolerant future of our world”. This also came with the assumed, problematic idea of resilience that assumes the individuals as more powerful than their surroundings.

There is something insidious about telling people stuck in refugee camps to only look at themselves for help and dismiss the national and international community’s obligation of aid. Here, refugees have the secret to success within them and there is no need to engage with the wider forces that created the conditions for asylum.

To say that all one needs to do is pull yourself up from your bootstraps and think positive cruelly dismisses the inhuman systemic treatment meted out to refugees at all stages of their journey to keep them from succeeding – and this often means just surviving. To be hopeful is always crucial, but so is the need for structural intervention.

'Helpless' refugees

In popular imagination, the refugee is seen as being helpless. Their entire lives are often seen to existent only in one shade – devastation. This is not to take away from the immense trauma of anyone who has been displaced, but instead to look at the strength of a stereotype in painting someone as just one thing.

Baraa Halabieh, an actor and refugee said in an interview with Huffington Post, “Someone once asked me, ‘Is there comedy in Syria’? I felt as if I was from a different species as if laughing and comedy belonged to some nations and not others. But it's universal."

This speaks to the wonder of seeing the refugees as resilient – all people are or can be resilient when required, but only some are forced into circumstances that demand resilience to survive. To praise that without acknowledging and addressing the trauma behind the resilience is to offer support only on the surface-level.

The event did often veer into saviour territory, especially when non-refugee speakers like photographer Georgina Goodwin said things that assumed a lack of agency for the subjects of her pictures like, “What drives me is that if I don’t go there and take photographs of these people, to the world they do not exist.” She proceeded in her talk to show us the pictures she took looking from the outside in. It would have been much more interesting to have given the camera to a refugee and enable her to tell her own story without any paternalistic framework.

This message is brought home by literally the next speaker in the line-up, a field officer who worked in the camps, Henok Ochalla, “Refugees who have fled horrible situations don’t just want to survive – they want to lead a life of dignity and respect.”

Influencing broader narratives – The ‘good immigrant’

Despite migration being in the news, the people affected are largely absent from the narrative. So, they are also seen as faceless. Events like these might give the crisis a human face, showing the refugees in a positive light.

Refugees in Kakuma refugee camp watching TedxKakuma live. Credit: Youtube screenshot

“It’s just a shame that the spotlight couldn't have also been used to make a political point about the wider situation but maybe that will happen as a consequence,” says Nuri Syed Corser, a migrant’s rights campaigner in the UK, to The Wire.

“We need to be noticed by the world and be seen as a creative place, where youths can put these talents to good use,” says John Thomas Muyumba, independent journalist and director, Youth Voices for Kakuma, in a video chat to Al Jazeera.

Kakuma is a hot spot for entrepreneurship, with an informal economy of 56 million dollars with many small businesses, performing arts, sports and education opportunities. Depicting this is incredibly important in breaking free of the dependent refugee stereotype.

However, it could also create an unfair binary of good versus bad displaced persons, with one who has earned the right to integrate with society and another who doesn’t deserve that. It puts an additional burden on the refugees – especially those who are already oppressed and financially weak in society and this could further disenfranchise them.

Perhaps a balanced approach is what’s best, where refugees are humanised and seen in the mainstream as multi-faceted, normal humans who have faced certain hardships because of where they live or whom they were born to.

Telling your own stories

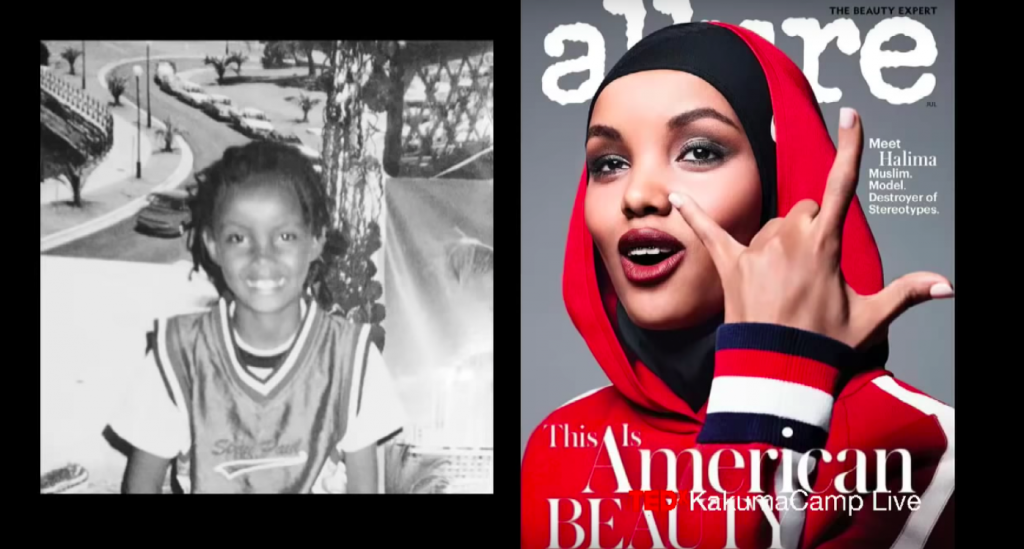

Somali American supermodel Halima Aden, who grew up in the camp and rose to fame as a hijabi American model, wants to redefine the narrative around refugee camps. “My story began here in Kakuma refugee camp, a place of hope,” she said at the TEDx event.

Pictures of former refugee and current American model, Halima Aden

Credit: Youtube screenshot of TedxKakuma Live

While uplifting refugee voices is crucial, perhaps more long-term support for the already existing creative initiatives by and for people living in camps would be more sustainable. It’s easy to say that TED just provides a platform, but creating an event in a specifically political area demands an untangling of the many complex issues that go with that space. It seems incomplete to offer a mic to oppressed people, but not question or engage with why their voices were stifled in the first place.

Listening to the refugee speakers at the event, the importance of authentic representation becomes evident – only they deserve to speak on their lived experience and frame their trauma and truth their own way. After all, only they know and it's only their stories to tell.

Like Emi Mahmoud, opening speaker at the event, author and spoken word poet said:

What survivor hasn’t had her struggle made a spectacle?

Don’t talk about the Motherland, unless you know that being from Africa means waking up an afterthought in this country,

Don’t talk about my flavour unless you know that my flavour is insurrection, it is rebellion, it is resistance

My flavour is burden, it is grit and it is compromise,

And you don’t know compromise unless you have rebuilt your home, without bricks, without hope, without any other option.

This article went live on June twenty-third, two thousand eighteen, at zero minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.