Despite Court Order, Sudha Bharadwaj Denied Basic Right of Phone Calls in Jail

Mumbai: Maaysha saw her mother, Sudha Bharadwaj, last on February 22. It was a day after Maaysha’s birthday; she turned 23 this year. In the mulaqaat (meeting) at Yerwada prison in Pune, Bharadwaj – an academic and human rights activist – was barely given five minutes to talk to her daughter who had travelled from Delhi just for this meeting.

The conversation, on an intercom across a glass window, was chaotic and interrupted by a dozen other undertrials also trying to catch up with their families simultaneously.

A week later, Bharadwaj and her other co-accused in Elgar Parishad case, one of the most controversial cases in the recent times, were transferred from the custody of the Maharashtra police to the National Investigation Agency (NIA). Later in March, the entire country was put under a lockdown over the coronavirus pandemic, impacting regular court visits, mulaaqats and phone communications of over four and half lakh prisoners across India.

Maaysha says the past two and a half months of the lockdown were spent in making desperate calls to the Byculla jail authorities and in finding ways to talk to her mother. Each of these calls were met with rude responses or a plain refusal to allow her to connect with Bharadwaj.

Also read: Over 600 Citizens Call for Temporary Release of Sudha Bharadwaj, Shoma Sen From Byculla Jail

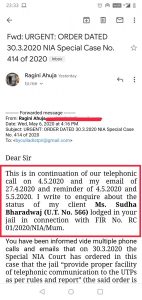

Bharadwaj’s lawyers too have been petitioning the Sessions court in Mumbai seeking bail, bringing her medical condition to the court’s notice and seeking the court’s permission to get to talk to their client over the phone. The constant persuasion yielded an order from the NIA court on March 30, where the Byculla prison authorities were directed to “provide proper facility of telephonic communication to the UTPs (undertrial prisoners) as per rules and report”.

Over two months and several reminders later, the order is yet to be honoured.

An old photo of Maaysha with her mother Sudha Bharadwaj.

“All of these efforts have only added to my anxiety. My mother is locked in the jail where at least one person has already been infected (by coronavirus). She is diabetic and has hypertension. Since the lockdown, I have not been able to even handover her routine medicines. I don’t even know how she is coping in there,” Maaysha tells The Wire.

Maaysha says the medicines that she had managed to courier across from Delhi to Mumbai have not reached Bharadwaj. Even money orders have not been possible in the past months, she says.

Since the cases of COVID-19 began to increase, the Supreme Court of India asked state governments to devise ways to address the issue and ensure safety of those in the prison. In Maharashtra, after several petitions and at least three deaths in three different jails, around 10 thousand of the over 37 thousand prisoners were released. Those arrested under specials Acts like the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act were not included in that list. Bharadwaj and her co- accused – all human rights activists and lawyers – did not qualify to be released on bail.

But Maaysha says she had at least hoped to stay in touch during this period. While the other accused in the case have managed to have at least a call or two every month to their lawyers, Bharadwaj continues to be deprived of that one basic access. “Her co-accused Shoma Sen could at least make that one call last month and another today (June 6). Sudha hasn’t got even that one chance to speak to either me or her daughter,” Ragini Ajuha, Bharadwaj’s lawyer, says. Ahuja had last met Bharadwaj in the jail on March 14.

Other male accused, all lodged at Taloja central prisons in the outskirts of Mumbai, have also been allowed two phones calls every month.

Screenshot of one of the many letters written by Sudha Bharadwaj's lawyers to the Byculla women prison, Mumbai.

Ahuja had since been writing to the Byculla prions and asking the authorities to at least follow the court orders. “They just won’t acknowledge our emails,” Ahuja says. In the past two and a half months, Ahuja has written five emails and has made innumerable calls. Each time repeating the same thing.

In court, the Byculla prisons authorities claimed that phone call service had been made available to both the female accused in the case. Bharadwaj’s lawyer and Maaysha, however, say this is a plain lie.

Ahuja rues that that the treatment meted out to Bharadwaj no longer “falls in the realm of a pretrial detention”. “It is punitive detention which borders on being life threatening due to the COVID-19 outbreak given her medical history. To deny an inmate even the basic humanity of a phone call is shocking,” Ahuja says.

Amnesty International India, an international human rights organisation has also termed the “process (of pretrial detention) itself as a punishment”.

“The suffering faced by the activists since the last two years indicate how the process is the punishment: shifted from one jail to another, investigations changing hands from the Pune police to the NIA and a smear campaign by the state and the media accusing them of being ‘anti-nationals’ working against the country. Now, as the COVID-19 pandemic rages across the country at an alarming rate with India ranking fifth globally on active COVID-19 cases, the activists are forced to live in overcrowded prisons as undertrial prisoners for simply exercising their rights,” Avinash Kumar, Executive Director of the organisation said, seeking their immediate release.

In the past months, the defence lawyers have focused on Bharadwaj and other co- accused like Varavara Rao’s medical condition. Rao is a 79-year-old poet and left-leaning activist from Hyderabad and was arrested alongside Bharadwaj in the case for their alleged involvement in organising Elgaar Parishad in Pune on December 31, 2017, which according to the investigating agency led to violence against Dalits visiting Bhima Koregaon memorial outside Pune on January 1.

Also read: In the Time of Coronavirus, the Right to Bail is Part of an Undertrial’s Right to Life

While the defence lawyers have been trying hard to debunk the allegations and have punctured severe holes in the electronic “evidence” that they have claimed to have gathered from accused, they have not been able to secure bail for a single person arrested in the case.

So far, 11 persons have been arrested in the case. Those arrested include Sudhir Dhawale, a writer and Mumbai-based Dalit rights activist, Surendra Gadling, a UAPA expert and lawyer from Nagpur, Mahesh Raut, a young activist on displacement issues from Gadchiroli, Shoma Sen, a university professor and head of the English literature department at Nagpur University, Rona Wilson, a Delhi-based prisoners’ rights activist, advocate Arun Ferreira, writer Varavara Rao and Vernon Gonsalves and Bharadwaj. The first five were arrested on June 6, 2018 and the remaining four in August, same year.

In April, this year, two more persons, civil rights activist and academic Anand Teltumbde and journalist- activist Gautam Navalakha were arrested.

This article went live on June seventh, two thousand twenty, at fifteen minutes past eleven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.