An Adivasi Hamlet Will Soon Be Flattened – to Make Way for the 'Prosperity Highway'

The huts of Janu Waghe and 15 other Katkari Adivasis – listed as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group in Maharashtra – are about to be overwhelmed by prosperity. Only it won't be their own. Their little hamlet in Thane district could soon be flattened by the state government's Samruddhi Mahamarg (‘Prosperity Highway’).

“This is my home. I have spent all my life here. My father and grandfather lived here. Now they [the Maharashtra government] are asking us to leave. We have not even been given any [written] notice,” says 42-year-old Janu. “Where will we go from here? Where will we build our home?”

His hut is located around half a kilometre from Chiradpada village in Bhivandi taluka. It’s a small room partitioned by a bamboo wall, and on the other side is a cooking area with an earthen stove. The floor is plastered with dung, the thatched walls rest on wooden poles.

Janu catches fish from 8 am to 3 pm every alternate day. His wife Vasanti walks across a narrow, uneven path for six kilometres to the market in Padagha town to sell the fish, carrying a basket weighing 5-6 kilos on her head. They earn Rs 400 a day for around 15 days of the month for their family of four. In between, when work is available, both Janu and Vasanti do daily wage labour on farms around Chiradpada, earning Rs 250 a day for plucking cucumber, brinjal, chillis and other vegetables.

Janu Waghe, Vasanti and their children. Credit: Jyoti Shinoli/PARI

One of the four huts in Chiradpada. 'Where will we go from here? ' Janu asks. Credit: Jyoti Shinoli/PARI

The 400-metre long viaduct will cross Chiradpada and continue to the east of the Bhatsa river. It will not only take away the homes of Janu and his neighbours, but also their traditional livelihood of fishing.

To help the land acquisition process, the state has made amendments to the Maharashtra Highways Act, 1955, and added state-specific amendments to the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013. Among the most important changes is the elimination of a social impact assessment.

As a result, the resettlement of landless labourers has been ignored, and any compensation for Janu and his neighbours is still being decided. MSRDC’s deputy collector, Revati Gaikar, told me in a telephone interview: “We are acquiring land as per the Maharashtra Highway Act. We can’t rehabilitate affected families, but compensation will be given for their losses.”

But Vasanti is sceptical. “Even if they [the government] give us money for taking away our house, how will we settle in a new village?” she asks. “We will have to get to know the people there, only then they will give us work on their farms. Is that easy? We won’t be able to continue fishing. How are we going to survive?”

Every month, Vasanti gets 20 kilos rice at Rs 3 per kilo and five kilos wheat for Rs 2 on the family’s Below Poverty Line ration card. “We can’t afford to buy dal, we eat fish with rice. At times, we get some vegetables from farm-owners after we finish their work,” she says. “If we go from here, we won’t be able to continue fishing,” adds Janu. “This fishing tradition has been handed down to us by our forefathers.”

His neighbour, 65-year-old Kashinath Bamne, recalls the day in 2018 (he thinks it was March or April) when officials of the Thane district collectorate surveyed the land in and around Chiradpada. “I was sitting at the doorstep. There were 20-30 officials holding files in hand. Seeing the police [among them] we got frightened. We couldn’t ask them anything. They measured our house and told us that we will have to vacate. Then they left. They told us nothing about where we will go from here.”

Also Read: In an Andhra Village, Ten Families Protest Displacement Caused By Polavaram Project

Kashinath and Dhrupada Waghe at their home. Credit: Jyoti Shinoli/PARI

Dhrupada selling fish at the market in Padagha town. Credit: Jyoti Shinoli/PARI

In December 2018, Kashinath participated in a one-day hunger strike outside the Thane collector’s office along with 15 farmers from Dalkhan village in Shahapur taluka and Ushid and Phalegaon villages in Kalyan taluka, in Thane district. “The collector promised to resolve the issue in 15 days. But nothing happened,” Kashinath says. They are still waiting for a written notice and for some idea of the amount they will receive as compensation.

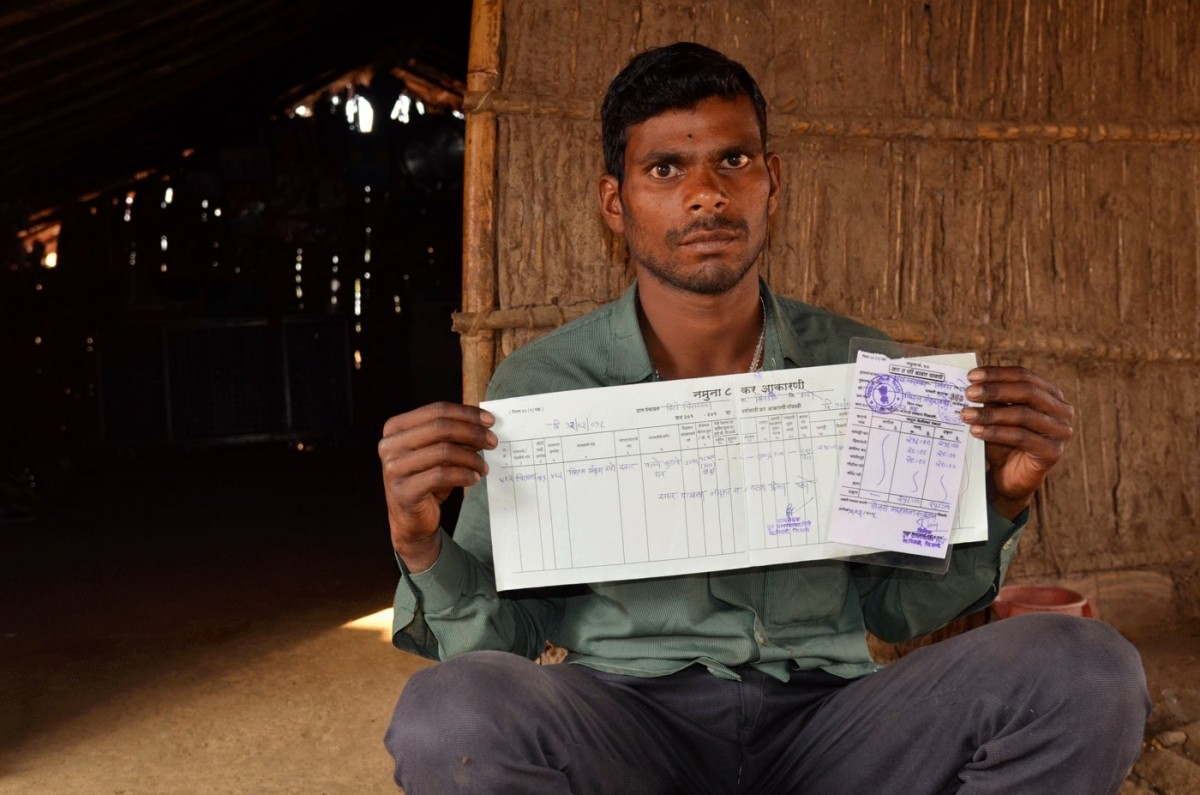

Kashinath and his wife Dhrupada depend on fishing too. Their three children are married – two daughters live in other villages, their son stays with his family in the main Chiradpada village. Looking at her dilapidated hut, Dhrupada says, “We never earned enough to repair it, just enough to fill our stomachs. The river is nearby, so the house gets flooded during the rainy season. But whatever it is, at least we have a roof over our heads.” She shows me receipts – the families here pay an annual house tax – between Rs 258 and Rs 350 – to the gram panchayat (village governing council). “This ghar patti, the light bill… we have been paying all this regularly. Are we still not eligible to get another house?”

Vitthal Waghe with his family. Credit: Jyoti Shinoli/PARI

Holding the house tax receipt that he hopes will help him and others through the coming eviction. Credit: Jyoti Shinoli/PARI

In Chiradpada village, 14 hectares of land is to be acquired for the highway, the EIA report says. In return, landowners will be given Rs 1.98 crore per hectare (1 hectare is 2.47 acres). This, says MSRDC’s Revati Gaikar, is a compensation formula of five times the market price. But farmers who refuse to give their land will receive 25 % less for the farmland, she adds.

“The government promised they won’t force farmers to give up their land. But in some cases they have threatened them with low compensation if they resist, in other instances tempted them with higher amounts,” says Kapil Dhamne, who will lose his two-acre farmland and two-storey house. “In my case, the land acquisition officer said first give your farmland, only then you will get the money for your house. But I refused to give my land and now they are acquiring it forcefully [that is, without consent].” In January 2019, after two years of visits to the collector’s office and numerous applications, Dhamne managed to get Rs 90 lakh as compensation for his house. He is uncertain how much compensation he will receive for his farmland.

Another farmer in Chiradpada, Haribhau Dhamne, who filed an objection in the collector’s office and refused to give up his farmland, says. “There are more than 10 names on our 7/12 [the saat/bara document is an extract from the revenue department’s land register]. But the acquisition officer took the consent of two-three members and completed the sale deed [to MSRDC]. This is cheating farmers.”

Ankush Waghe: 'How will the fish survive? The river is our mother. It has fed us'. Credit: Jyoti Shinoli/PARI

Meanwhile, in Chiradpada’s fishing hamlet, Ankush Waghe, 45, is walking along the sloping pathway beside his hut toward the river, to prepare his boat for fishing. “This is the same way my father would walk to the river. This will stop once the road [highway] comes. And all that cement, the machines will pollute our river. It will create noise. How will the fish survive? The river is our mother. It has fed us.”

“What we will do?” wonders Hirabai, Ankush’s wife. Their elder son Vitthal, 27, will also lose his hut – one of the cluster of four – to the highway. He works at a stone quarry near Sawad village, around 6-7 kilometres away, and earns Rs. 100 a day breaking and loading stones onto trucks. “We all went to Bhivandi’s Public Works Department [in November 2018].” Vitthal says. “They asked if we had the notice to evacuate [which they have not yet got]. No one among us is well educated. We don’t know anything. We should get alternate land. If tomorrow they ask us to leave, where we will go?”

The destruction of the river, the displacement of communities, rehabilitation – these and other concerns were voiced in a public hearing in Vashala Kh. village in Thane district held by the Maharashtra Pollution Control Board in December 2017. The concerns were ignored.

By 4 pm, Dhrupada’s son returns with a plastic basket full of tilapia fish. Dhrupada gets ready to go the market in Padagha. “My life has gone by selling fish. Why are they snatching this bit too from our mouths? Repair this dusty pathway first. We have to walk a long way to the market,” she says, sprinkling water on the fluttering fish in the basket.

This article went live on April third, two thousand nineteen, at zero minutes past seven in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.