Interview | Sudhir Dhawale's Work Will Go on

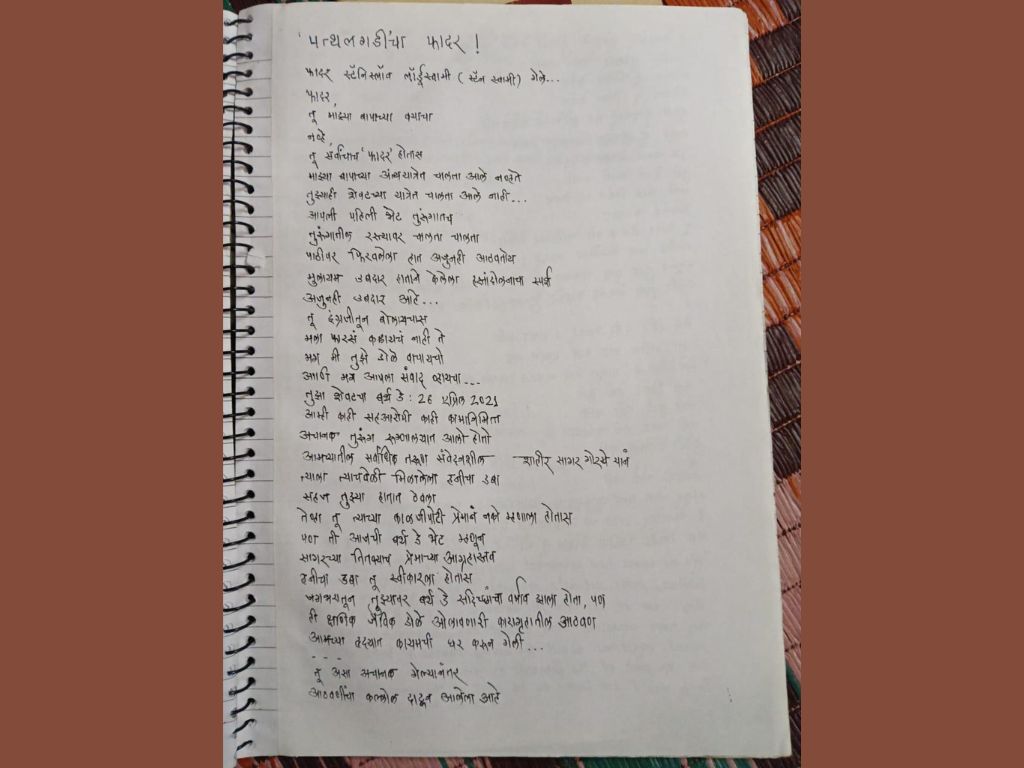

Mumbai: A day after Father Stan Swamy passed away, Sudhir Dhawale, overcome with emotion, sat down in his barrack and wrote a long poem. “Words just flowed,” he says.

Dhawale, a prolific writer, author of several books, and editor of the radical anti-caste bi-monthly magazine Vidrohi, had never before written poetry. This was his first. But in the three-and-a-half years since Swamy’s death, Dhawale has written at least a hundred more – on issues that directly impact him, on news that stirs his emotions, on politics that kept him awake in prison, on Modi, on the "Manuwaadi" government, and even on society’s apathy towards “corroding democracy.”

“Father Swamy made me a poet,” he shares, as he shows me his prison writings, sitting in his rented 15x15-square-foot office-cum-home in the slums of Govandi. Long before his arrest, this area has served as workspace and home for him, and as a safe haven for cultural activists and singers. The title of the poem is Pathalgadicha Father (father of Pathalgadhi); its Marathi words softly describe Swamy as everyone’s father, both inside and outside the prison. It testifies to how deeply the death broke Dhawale.

Sudhir Dhawale's poem after Father Stan Swamy's death. Photo: Sukanya Shantha/The Wire.

Dhawale was arrested on June 6, 2018, one of the first six of the 16 people arrested in what came to be known as the Elgar Parishad case. Dhawale is the ninth (Rona Wilson was also released along with him on January 24) to be released from jail, after 2,424 days of incarceration. The duration of imprisonment without trial was one of the primary reasons that the Bombay high court deemed him and Wilson fit for release.

‘Both very violently stifled dissent’

The Elgar Parishad case was not the first time that Dhawale came under the state’s scanner. In 2011, when the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government was still in power, Dhawale was booked under the same stringent Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. He spent over 40 months in jail before he was finally acquitted of all charges in May 2014 – just days after the Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance government came to power.

In a strongly worded judgment, the then special sessions court judge R. G. Asmar pointed to the possible “concoction of the case” against Dhawale. “How can highlighting the wrongs prevalent in society, and insisting that there is a need to change the situation, be considered as evidence of them being members of a terrorist organisation?” Asmar had noted in the judgment.

After over 10 years of incarceration in the past decade and a half under two different regimes, Dhawale says the governance under both parties has “not been very different.”

“They have both very violently stifled dissent of every kind,” he points out.

He takes a moment to think, then points to one “qualitative distinction.” “Under Congress rule, it was common to get a case concocted, and then the state (government) would spend years proving it before it finally failed. But under BJP rule, the approach is different. Here, the government plants evidence, and you are left on your own trying to defend that the material planted doesn’t belong to you.”

Also read: Jail Authorities Are Blocking Letters From Elgar Parishad Arrested to Their Loved Ones

Personal, political and fighting back

Dhawale’s arrest in the Elgar Parishad case coincides with several important events, both personally and politically, for him. He was arrested on June 6, 2018, and while he was still in the custody of Pune police, his close friend, Shahir Shantanu Kamble (on whose life the film Court was based), passed away. Then followed the reading down of Article 370, the COVID-19 pandemic, the death of his close friend and actor Vira Satidhar (the protagonist of Court), the Delhi riots, the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act/National Register of Citizens protests, Father Swamy’s death, and, more recently, professor G. N. Saibaba’s death. In response to each of those events, Dhawale wrote. A lot.

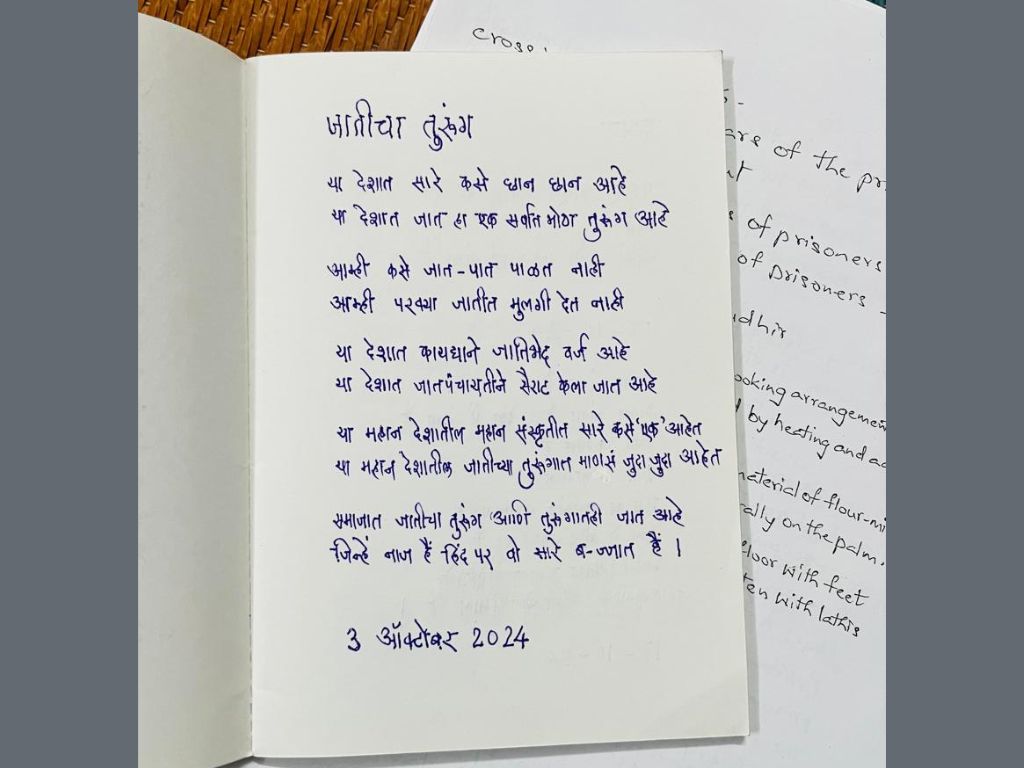

When the Supreme Court delivered its judgment in the caste-in-prisons petition filed by this author, based on The Wire’s investigation, he wrote yet another searing poem.

Sudhir Dhawale's poem after the caste-in-prisons judgement by the Supreme Court. Photo: Sukanya Shantha/The Wire.

Two of his books were published while he was still in jail; a few more, which he knows might potentially land him in more trouble, are ready manuscripts waiting to be published.

Dhawale’s bail was hard-earned. He was released after the Bombay high court acknowledged the “inordinate delay” in commencing trial in the case. The NIA has yet to even frame the charges in the case, and considering that in their several volumes of chargesheets filed in many phases, there are over 300 witnesses to be examined, the court let him and Wilson out.

Dhawale is mindful not to delve into the merits of the case, considering the trial has yet to commence. But he is equally mindful that the state doesn’t achieve what it set out to do: stop him from speaking his mind. “At the onset, it might appear that the state has won by putting us behind bars. But the struggles haven’t stopped. The common man is fighting back, and that spirit is what we tried all along to keep alive,” he tells me.

Politics of ‘co-opting’

Dhawale was one of the main organisers of the Elgar Parishad event held on December 31, 2017 at Shaniwarwada in the heart of Pune. Shaniwarwada was a well-thought-out location, a place that is synonymous with the Brahmin rule of the Peshwai regime in the region. The BJP-led Maharashtra government later accused the Parishad of “causing riots” at Bhima Koregaon, even when the victims and witnesses of the violence had blamed two right-wing leaders, Manohar Bhide and Milind Ekbote, for disrupting an otherwise peaceful congregation at Bhima Koregaon.

Later, more allegations were levelled against the organisers of Elgar Parishad, and more people, including those who had no role in the event, were accused of harbouring plans to “destabilise the government,” “funding the banned Maoist movement,” and even hatching a plan for the “Rajiv Gandhi-style assassination” of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. An accusation of such a serious level is, notably, yet to be proved. Dhawale says that, besides those from Maharashtra, he hadn’t had the chance to meet or interact with the others accused in the Elgar Parishad case. “The BJP brought us together,” he chuckles.

When asked why, according to him, he or others were arrested in the case and whether it was his leftist ideology or his identity as a Dalit Ambedkarite man that got him in trouble, Dhawale spends no insignificant time explaining how he views the two. “I am a follower of Marx, sure, but I am also an Ambedkarite. I look at Ambedkarism as a radical politics in itself. At a time when the BJP and the RSS are trying so hard to co-opt Ambedkar, my effort has only been to put forth my Ambedkarite views without fear,” he says.

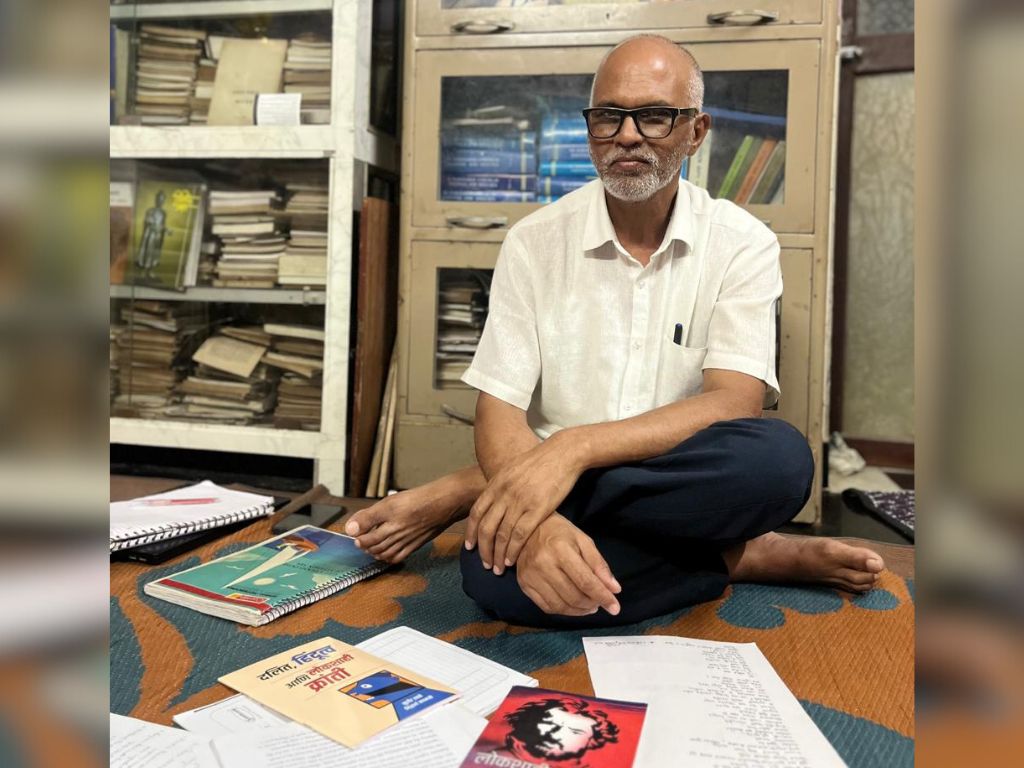

Sudhir Dhawale with his books. Photo: Sukanya Shantha/The Wire.

Dhawale, born in Nagpur, has founded many organisations. Republican Panthers Jatiantachi Chalwal (anti-caste republican panthers), Radical Ambedkar, and Ramabai Nagar-Khairlanji Hatyakand Virodhi Sangharsh Samiti are among his widely known organisations.

Dhawale recalls COVID-19 as the worst phase of his prison life. “Kaayamchi marnyachi bhiti (the constant fear of death)” is how he describes the pandemic phase. The news of the pandemic reached jail through news channels that prisoners could access from one TV in every circle (Taloja has eight such circles, with 16 barracks in each of them). “The TV channels would keep telling us to clean our hands. But as prisoners, we would get just a bucket of water for everything – from washing, bathing, drinking to toilet. It was bizarre,” he recalls.

He says there were days when almost all prisoners in a barrack would be seen confined to their beds. “No prisoner was taken outside. But more and more were filled in every day. In my barrack, which had a capacity of 23 prisoners, there were over 60-70 stuffed at a time,” he recalls. COVID kits (masks and sanitizers) were available only after the second wave, he adds.

The dreaded anda cell

Forever a rights activist, Dhawale continued his activism even in jail. When Dhawale refused to remove his footwear during the regular rounds by the superintendent of the jail, he was branded a “difficult prisoner.” He was soon sent to the dreaded “anda cell” at Taloja. Dhawale didn’t give up; he filed complaints and RTIs. A few appeals are pending even three years after he first began his agitation.

The anda cell (named for the egg-shaped solitary confinements in Indian jails) of Taloja, Dhawale says, is the worst he has ever lived in. Dhawale spent 23 months in solitary confinement. Several of his co-accused were also shunned there for questioning the authorities or moving applications in court. “The jail authorities were scared that if our questioning turned into a full-blown agitation, they couldn’t handle things anymore,” he says.

Taloja central prison, spread over 27 hectares, is one of the most recently built prisons (built in 2008). It has a massive two-story anda-cell complex, the only one in the state, and perhaps country, with so many solitary cells. The cell, unlike other jails that are egg-shaped, is built like a circle. They have four internal partitions with 6-7 small rooms in each partition. “Those lodged on the ground floor at least get to walk in the limited free space available in the centre. But for those on the first floor, there is no such scope. They get no sunlight or fresh air for as long as they are lodged in there,” he says.

“The structure is built to kill your very understanding of freedom,” adds Dhawale.

Jails have their own rules – some written and most unwritten. So when letters are sent out or received by those incarcerated, they are all a “second-hand reading”, Dhawale says. “It is a given that the jail authorities will first read the communication before letting it in or out of jail.” But in the case of those jailed in the Elgar Parishad case, the level of scrutiny was multi-layered. The letters would be sent all the way to the Anti-Naxal Operation (ANO) cell situated in Nagpur. This, Dhawale had challenged before the State Human Rights Commission. His complaint, drafted in Marathi, was rejected. An identical complaint drafted by his co-accused Arun Ferreira, however, was accepted and later, the SHRC even directed the state to pay Ferreira Rs. 2 lakhs as compensation for violating his rights.

Now that Dhawale is out, he says, he will continue with the work he did before his incarceration. “The work didn’t stop. While I was in jail, my team carried the work forward. I continued to write too while in jail,” he says. “The work will go on.”

This article went live on February fourth, two thousand twenty five, at zero minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.