J&K: Endless Wait for Hearings in Public Safety Act Cases Agonises Detainees, Kin

Srinagar: On June 26 last year, 29-year-old Amir Bashir War, an operating theatre technician at a medical NGO, was at work tending to patients with medical emergencies in an ambulance as they were being ferried to a hospital. He received a call from the Jammu and Kashmir Police post in Warpora village in the north Kashmir town of Sopore. Amir was ordered to appear before the police. He immediately rang up his father, 62-year-old Bashir Ahmad, who left his home soon after the call to join Amir.

"We thought it was regarding his passport application," Bashir Ahmad told The Wire.

But upon arriving before the police, the father was ordered to leave while Amir was asked to stay. The following day, Amir was arrested and bussed across the mountains to the Kot Bhalwal prison complex in Jammu. He was slapped with the Public Safety Act (PSA), the Union territory’s strict preventive detention law.

His PSA dossier, which lists out the grounds of detention, accuses Amir of being associated with the Pakistan-based terrorist group Lashkar-e-Tayyaba (LeT), feeding and sheltering terrorists, and using encrypted communication tools to avoid detection. It also charges him with "aggressively" campaigning in favour of the terrorist group on social media.

Amir Bashir War's father shows a picture of his son.

The family, however, strongly contested this and filed a habeas corpus (h/c) petition at the Jammu, Kashmir & Ladakh (JK&L) high court last year, for getting the PSA case against Amir quashed.

There is no FIR registered against the 29-year-old detainee, something his lawyer, who spoke to The Wire, said could help get his detention nullified. "We are arguing that the detention is based on vague grounds and not having an FIR is in support of our argument," Bashir Tak, the lawyer said.

Yet, the case has come up for hearing only once over the past six months despite it figuring in the high court's 'cause list' on seven occasions since.*

Amir is not the only PSA detenu to find himself facing this predicament. The Wire spoke to at least a dozen families who have had their loved ones detained under the Act, as well as to the lawyers who are fighting these matters. All of them unanimously claim that the "lack of hearing" in cases pertaining to detention was becoming a "regular affair" especially after the former state's special constitutional status was revoked in 2019. The lawyers shared concerns over what they described as detention cases being pushed to the tail-end of the daily cause lists so that by the time their turn arrives, the clocks strike past 4 pm and the courts call it a day.

On June 9, The Wire visited the high court complex in Srinagar to speak to the various families who were there to attend the day's proceedings as the cases of their imprisoned relatives were scheduled for hearing. Among them was Sadia Manzoor** from the Kulgam district of south Kashmir. Her 24-year-old brother, Imran Manzoor**, was arrested by the security forces in February 2022 from his store where he sold garments. His family said he was lodged in different prisons across the Valley before being flown to the Bareilly central jail in Uttar Pradesh.

Also read: How the Public Safety Act Continues to Haunt Kashmir

His father Manzoor Ahmad doesn’t remember the last time the case had come up for hearing (high court documents show it was on March 7 this year) but whenever it was listed, the family would travel 70 kms to Srinagar to attend the court proceedings which were always few and far between.

"We come here each time his case is listed for hearing," she says. "We wait for the whole day, sometimes without food, only to be informed that the judges couldn't hear the case. They take up supplementary and regular cases and those that have come from the final hearing are not prioritised."

Manzoor’s case was scheduled in the daily cause-list 25 times since May last year but orders have been passed only on five occasions, of which four pertain only to the court instructing the respondents (i.e. J&K UT) to file detention records. On June 9, Manzoor’s case was listed 104 on the serial list. His family had already resigned itself to the fct that it will not be heard. "We had to leave in the evening," Manzoor Ahmad later told The Wire over a phone call.

What is the PSA?

J&K Public Safety Act 1978 is a controversial preventive detention law that allows law enforcement agencies to detain individuals pre-emptively for six months and prolong their detention for up to two years, depending on the nature of the threat the authorities believe they could pose to the "maintenance of law and order" and "security of the state".

Also read: Advisory Board Examining Detention Orders in J&K 'Systematically Subjugated'

There's no mechanism to get bail under PSA. The cases are moved to an advisory board – whose members are selected by the administration itself – which determines whether they are filed on reasonable grounds. If the case doesn’t meet the board’s admissibility test, it is revoked. Official documents obtained by legal researchers in 2018 revealed that for 2016-17, only 0.6% of PSA cases by the authorities failed to get past the board. In the remaining 99.4% of cases, involving 998 persons, the board confirmed the detention orders.

The only option left for the families of the detained persons is to then appeal against their incarceration by filing a habeas corpus petition in the JK&L high court.

Although the PSA is analogous to the National Security Act, 1980 (a federal law), the latter is less severe because it allows a person to be detained for a maximum of 12 months as opposed to two years in the case of PSA.

Even as the Union government rammed hundreds of central laws through the Union territory as a consequence of reading down Article 370 — under whose aegis the PSA was first legislated — it did not substitute the PSA with NSA. Instead, it retained the law within the legal framework of the erstwhile state, something that human rights groups such as Amnesty International have slammed.

Also read: Explainer: How the Public Safety Act Has Been (Mis)used in J&K

Growing number of habeas corpus appeals

Based on the high court data accessed by The Wire, the petitions challenging detention under PSA appeared to have spiked sharply last year. In 2019, when Article 370 provisions were scrapped and the J&K state bifurcated, the high court received 507 such pleas. In the following years, the figures stood at 203 (in 2020), 327 (in 2021), and 841 (in 2022) respectively, signifying a sharp increase. This year so far the high court has received 266 petitions out of which only 16 have been disposed of while 250 are pending.

According to lawyers who fight PSA cases at the JK&L high court, two significant changes that judicial authorities have implemented hold the key to understanding such a spike. On April 17, 2019, three months before Article 370 was scrapped, an order issued under the aegis of the registrar general at the J&K high court sought to make rationalisation of nomenclature and categorisation of cases “more scientific and in tune with nomenclature prevalent in other high courts of the country”.

The J&K High Court Registrar General's April 17, 2019 notices along with its Annexures which affirm the change of nomenclature from Habeas Corpus to WP (Crl).

In the annexure accompanying the document, the new nomenclature for habeas corpus cases has been changed to Writ Petition Criminal, WP (Crl).

The slow grind

According to the lawyers, the J&K high court followed a particular convention pursuant to which habeas corpus pleas were preferentially prioritised and heard expeditiously. "We had what we call ‘case flow management rules’ at the high court," said one senior lawyer pleading anonymity. "Under those rules, liberty matters were required to be decided within 15 days. Although no PSA cases were decided within 15 days, at least disposal used to happen in a few months' time."

He said that after the April 2019 notification, habeas petitions were being treated on par with what he termed ‘routine matters’ and therefore not prioritised in ways in which they were previously.

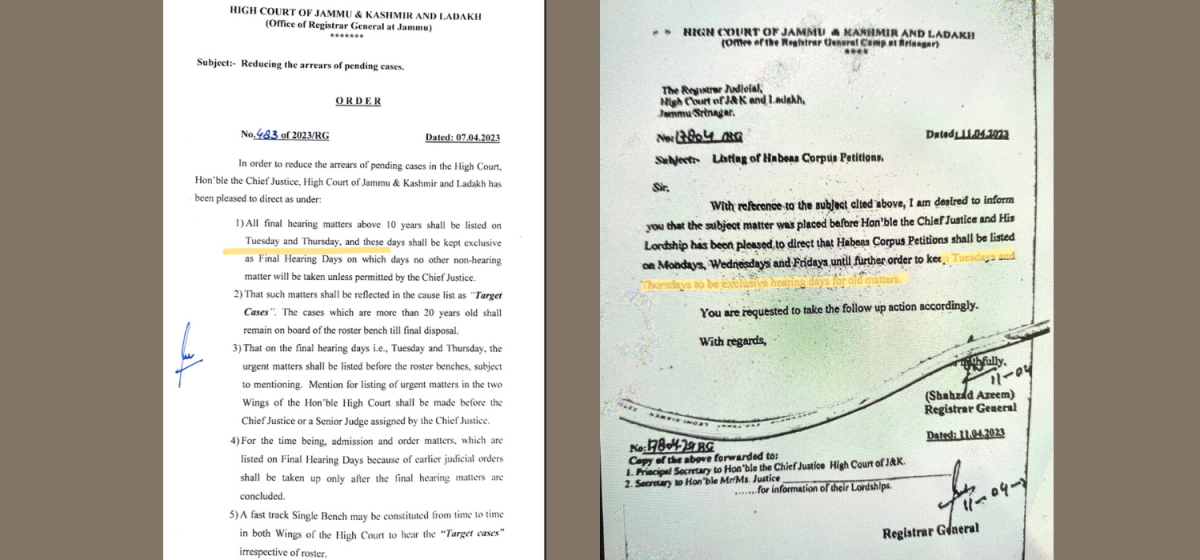

Another JK&L high court circular dated April 7, 2023, stipulates the scheduling of cases pending "above ten years" on Tuesdays and Thursdays. The circular, like the previous one, is also prefaced with good intentions. It mentions that the new rules have been framed to "reduce arrears of pendency cases". It designates these two days exclusively for ‘final hearing’ during which "no other non-hearing matter will be taken unless permitted by the chief justice".

On the right, the JK&L High Court Registrar General's notice which stipulates scheduling the cases “above ten years” on Tuesdays and Thursdays. On the left, the Registrar General's notice confirming that habeas corpus petitions shall be listed on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays until further order to keep Tuesdays, Thursdays to be exclusive hearing days for old matters.

Four days later, on April 11, yet another communication by the registrar general, citing instructions by the chief justice of JK&L high court, ordered that “habeas corpus petitions shall be listed on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays until further order to keep Tuesdays, Thursdays to be exclusive hearing days for old matters".

G.N. Shaheen, a senior lawyer and spokesperson for J&K High Court Bar Association, said that these notices have led to a situation where cases filed under ‘orders’, ‘admissions’, ‘before-notice’ and ‘after-notice’ categories cram the cause-list on the remaining three work days in the week as a result of which cases concerning personal liberty find themselves on the tail-end. "Detention matters are otherwise a priority across the world," he told The Wire.

'Decide the cases on merits'

The wait has been grueling for Idrees Dar (30), a labourer from the south Kashmir district of Kulgam. His 19-year-old brother Mohammad Ilyas was arrested by the police on the apprehension that he was likely to join a militant faction. His PSA document issued by the Kulgam dstrict magistrate, accuses him of being involved in stone-throwing protests in September 2021 when demonstrations had erupted following the demise of Hurriyat leader Syed Ali Shah Geelani. Ilyas was arrested in April 2022, Dar said.

He was first lodged in Kot Bhalwal jail in Jammu before being relocated to a Haryana jail that August. His case was listed 24 times but the court documents show only three orders. "We have approached court but every time the case is listed, it hovers around serial numbers 120, 130, or 125. Our turn never comes," Dar said.

The last occasion when judges took up Ilyas’s petition was on March 31 this year. “I appear at the court on hearing days dutifully,” Idrees says. “I just pray that the judges take steps that expedite the hearing process. I am not asking for amnesty. The case should be decided on merits. But at least they need to hear us.”

Habeas corpus is an overriding priority

Legal experts who spoke to The Wire for this story said that although the change in nomenclature to WP (Crl) was not of much significance, it is unfortunate that this has led to the sidelining of PSA cases. "A request has been pending with some high courts to have some uniformity in nomenclature so that data of cases can be easily picked up by the computer," said Justice Madan. B. Lokur, a leading Indian jurist and former Supreme Court judge.

Justice Lokur said that every high court gave priority to the habeas petitions because the detention is without trial. And this has been the practice in all democracies. “Sir Alfred Denning [an English lawyer and judge] in ‘The Hamlyn Lectures’ in 1949 says that all other work stops when a habeas corpus petition is mentioned for listing. So, it is terrible that cases are not being taken up. Multiple adjournments is totally unacceptable. The matter should be taken up with the chief justice," he said. Justice Lokur added that habeas petitions usually do not take long to decide. "So, if they are taken up, it will not unduly disturb the list of cases for the day. Even if it does, it doesn't matter because of the importance and urgency in hearing [these] petitions," he said.

Shaheen told The Wire that members of the Bar Association had approached the present chief of the JK&L high court, Justice N. Kotiswar Singh, regarding this matter. “On behalf of the association, we requested the hon’ble chief justice to devise a mechanism in light of the Supreme Court orders,” Shaheen said.

Referring to his personal frustration with the infrequent hearings, Shaheen said that he gets tens of phone calls every day from relatives of detainees. "Because hearings are few and far between," he said.

The high court's interventions

The Wire parsed through more recent official communications pertaining to the functioning of the high court which reveals express efforts to get such cases expedited. What could not be established, however, is whether these interventions came as a response to the growing clamour over the issue of fewer hearings in habeas matters.

On June 7, the Twitter account of a Kashmiri lawyer reporting proceedings from the JK&L high court quoted Justice Sanjay Dhar sharing concerns with the J&K government’s additional advocate general over habeas matters not being taken up in his court and adding directions that such petitions must be takne up before his court at 3:30 pm every day.

Before that, in a notification dated April 26 this year, the registrar general rolled out a new roster valid for a period between May 1 and June 17. Appended to the circular were a series of notes, one of which directs the judicial benches to hear cases related to personal liberty on priority. "If the listed matters related to personal liberties are not taken up for any reason in the first half of the day in that event these matters shall be taken up by the concerned benches at the beginning of the post-lunch session as per the convenience of the concerned roster bench,” it reads.

A copy of the fresh roster valid between July 24 and July 29 at JK&L High Court which reiterates 'Note 8' of the previous roster laying down guidelines that if the listed matters related to personal liberties are not taken up for any reason in the first half of the day in that event these matters shall be taken up by the concerned benches at the beginning of the post-lunch session as per the convenience of the concerned roster bench.

The fresh roster valid between July 24 and July 29 also reiterates these instructions. Yet the families The Wire spoke to said it has hardly improved things on the ground.

Lawyers fighting PSA cases had a bleak impression to share. "Today, some of my cases figured at serials 133 and 135 on the list. Yesterday, one case was at serial 244 yesterday, another at 256,” Bashir Tak, the lawyer at JK&L court said in a recent interview. “There’s was no chance a case placed at such a farthest end will be heard."

"My son’s case was listed for hearing on the 10th and 21st of July," Bashir Ahmad, Amir’s father said. "On both these dates, the case wasn’t heard even though he was on serial 59 (general category) and on serial 11 (final hearing)," he said. "The hon’ble judge, however, did take up two other cases, one of which was quashed and another reserved."

'PSA revocation doesn't amount to being innocent' says police

Senior J&K police officials who spoke to The Wire said that getting released from the PSA detention does not imply that the detainee is 'innocent' of the claims the state makes against them.

One officer who spoke on condition of anonymity cited the case of Lashkar-e-Toiba’s Sajjad Tantray who was killed in November last year. "Tantray was initially detained under the PSA in 2019. After getting released, he was found to be responsible for attacking two migrant labourers in Bijbehara in south Kashmir last year. Similarly, we had cases of terrorists like Zubair Turray who too were released from their PSA detentions before they joined terrorism."

It is perhaps for this reason that the J&K police has in recent times started training sessions so that officers are well-equipped to prepare more foolproof dossiers that are not quashed in the courts on technical grounds. According to a report in The Print, the J&K police in 2022 improved their tally of successfully seeing PSA cases through judicial scrutiny. The nullification of PSAs at the hands of the high court, the report said, came down from 81 (out of 134 detentions) in 2020 to just 49 (out of 749) in 2022.

Another officer speaking to The Wire drew attention to what he called the decimation of "organised militant recruitment" which has led to a change in the ways militancy is being operationalised in Kashmir – as a result of which the law enforcement agencies are increasingly relying on the combined strength of PSA and Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) to keep the "known offenders out of circulation".

"Militancy has turned more underground. The recruiters make careful assessments of who they should enlist," he explained.

The officer said that recruiters reached them individually through encrypted chat applications. "These networks are widespread but the work apportioned to every next person down the chain is minimal. One may argue in court that merely providing a tiffin box or ferrying a bag from one place to another doesn’t amount to a big offence. But we have to look at the whole picture. These individuals are small nuts and bolts of the same apparatus that mechanises the bigger operation," he said. "Courts will obviously see things through principles of natural justice. But for us, it is the question of liability," the officer said.

At the same time, the fact that regular cases are not filed against detainees before they are placed in detention under the PSA implicitly means that the police know the evidence they have of an individual's involvement in militancy or the commission of a crime likely won't hold up in an actual trial.

A review of the PSA cases being quashed

The Wire reviewed 13 PSA cases that the JK&L high court quashed in the year 2023. The reasons offered for quashing these detention orders show that despite the seriousness of offences imputed to the detainees, PSA orders end up being invalidated because the plaintiff's counsel were able to prove that the detaining authority – which in the case of this law are the district magistrates (DMs) acting upon dossiers submitted by superintendents of police (SPs) or higher-ranked officers – did not apply their mind while authorising the detention, or that the respondents (the Union territory of J&K), did not supply the detainees with the grounds of detention on the basis of which they could have appealed against their internment.

In the cases of Abid Hussain Ganie from Anantnag, Naseer Ahmad Dar from Ganderbal, Waseem Ahmad Pandith from Pulwama, Javeed Lone from Bandipora, Rouf Mushtaq Najar of Shopian and Ghulam Ahmad Waza of Bandipora, the judges pointed out that there is a mismatch between detention record produced by counsel (which had no copies of FIR) and submissions made by the J&K government (which gave reference to a certain number of FIRs.) On the basis of this, the judges determined, “The failure on the part of the detaining authority to supply the material relied [on] at the time of making the detention order to the detenu renders the detention order illegal and unsustainable."

In Ganie’s case, the court observed, “Surprisingly, when no FIR is shown to have been registered against the petitioner, then how come 27 leaves of FIR, etc., have been provided to him? This exhibits total non-application of mind and overzealousness on the part of the detaining authority, which casts serious doubt about the authenticity of the receipt.”

In another case, while rescinding the PSA orders against Zahoor Ahmad Sheikh of Beerwah and Umar Rashid Ganie of Anantnag, the judges noted that the dossier of the SSP and the detention order of the DM are identical copies of each other and that this indicated the detaining authority did not exercise its own mind, which is an important prerequisite to ensure that a PSA order survives judicial scrutiny.

In the cases of Umair Mushtaq Rather from Kulgam, Shafayat Amin Shah from Shopian, and Molvi Muhammad Amin Pala from Anantnag, the court observed that material relied upon by the detaining authority was not furnished to the detainees and as such made their PSA “unsustainable”.

While quashing the PSA order against journalist and editor Fahad Shah and one Feroz Zargar from Kulgam, the judges noted that the detaining authority cannot use both expressions “prejudicial to maintenance of public order” as well as “prejudicial to security of the state” as they have different connotations and are demarcated on the basis of gravity and cannot be used simultaneously which proves that the "detaining authority has not applied its mind while passing the order of detention.”

*When this correspondent was still working on this story, Amir's case was heard by the judges for the second time and it was adjourned because his counsel didn't show up.

**Name changed.

Shakir Mir is a Srinagar-based journalist. He tweets at @shakirmir.

This article went live on July twenty-ninth, two thousand twenty three, at zero minutes past seven in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.