Ramesh Koul and His Bag of Letters: A Picture of the Kashmiri Pandit Under BJP

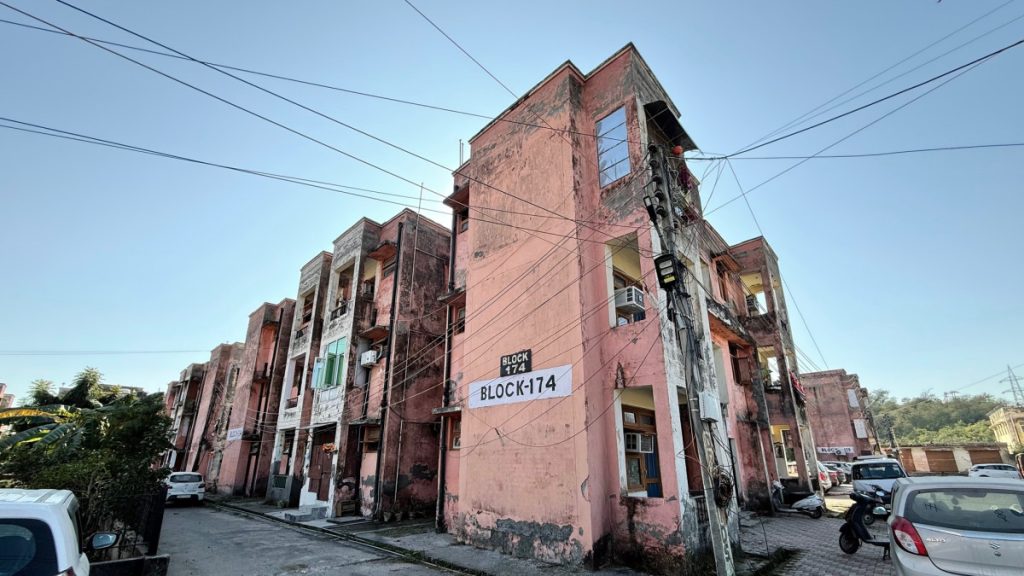

Jammu/Anantnag: Soft sunlight makes its way into Ramesh Koul’s tiny apartment in Jammu’s Jagti Camp. The Kouls are one of the 5,000 families housed in Jagti Camp, meant to be a temporary rehabilitation for Pandit families, who fled Kashmir during the deadliest phases of militancy in the 1990s.

For three decades, Koul has held close a plastic bag of paperwork with revenue extracts, insurance receipts, land transfer orders, and complaint copies. Each document is a fragment of what he says has been “a long, slow erasure” – the disappearance of his home, his land, and any acknowledgement from the state that promised to protect him.

Koul left Kashmir’s Bijbehara in the early 1990s. In his fifties and living in two-room quarters in Jagti, he places the bundle of papers on a carpet to display his exasperation. “This is my life,” he says quietly. “And for 30 years nobody – not even Modi ji – has answered me.”

For Koul, home is still in South Kashmir’s Bijbehara. The land is still his according to the papers in Koul's bag. But the other documents inside that bag tell a story of contradictory revenue entries, insurance receipts that did not result in payouts, official acknowledgements that did not result in any action, and the slow bureaucratic evaporation of a displaced person’s rights.

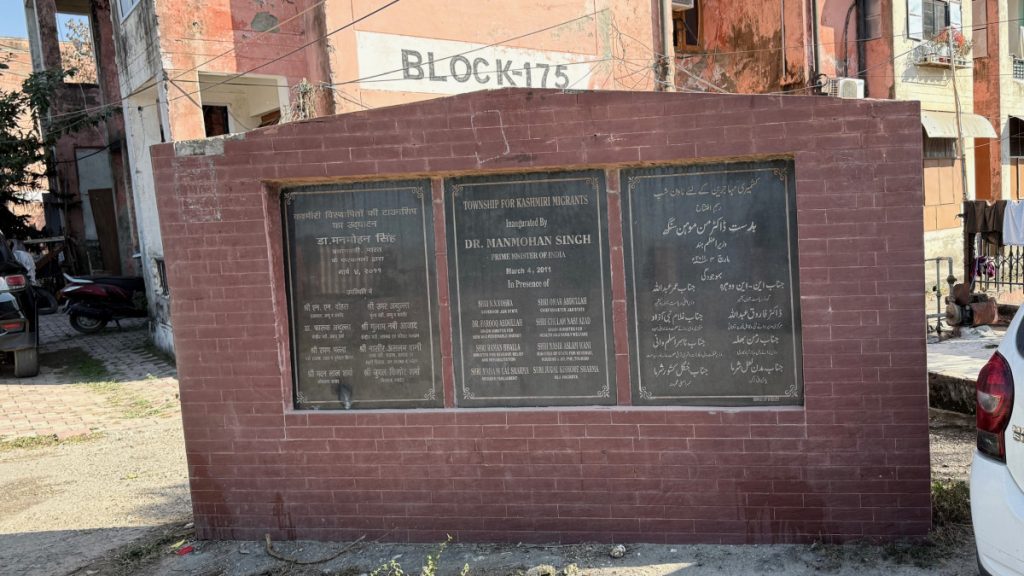

Jagti township houses Pandit families. Photo: Tarushi Aswani

Proof and memories

Koul feels that the state and all its systems have no memory of his struggle even though he himself has held onto it for many years.

One of the few clear victories in Koul’s 30-year struggle came only recently. For decades, his small patch of paddy land had remained in the possession of a local man named Ahmed Dar, whom Koul names as an encroacher.

The revenue documents he now keeps – mutation records and formal orders from the Tehsildar – tell a different story. In 2023-24, the J&K administration finally certified what Koul had been saying since the 1990s: the land is his. The latest handwritten certification, stamped and signed by revenue authorities, states that the land “stands in the name of Shri Ramesh Kumar Koul, resident of Bijbehara.” A correction order rewrites earlier clerical contradictions. A field inspection report confirms physical possession. It is the kind of rectification that should have taken weeks, not half a lifetime.

Koul mentions the local tehsildar Sajad Ahmad and Deputy Commissioner of Anantnag, Syeed Fakhrudin Hamid, who made sure the encroacher left his land. “They did their job there,” he says, with warmth, while gripping the paper so tightly that the edge curls. “Why can’t the system do it everywhere?”

Koul's agricultural land was recently freed from an encroacher owing to help from local administration. Photo: Tarushi Aswani

Letters of longing

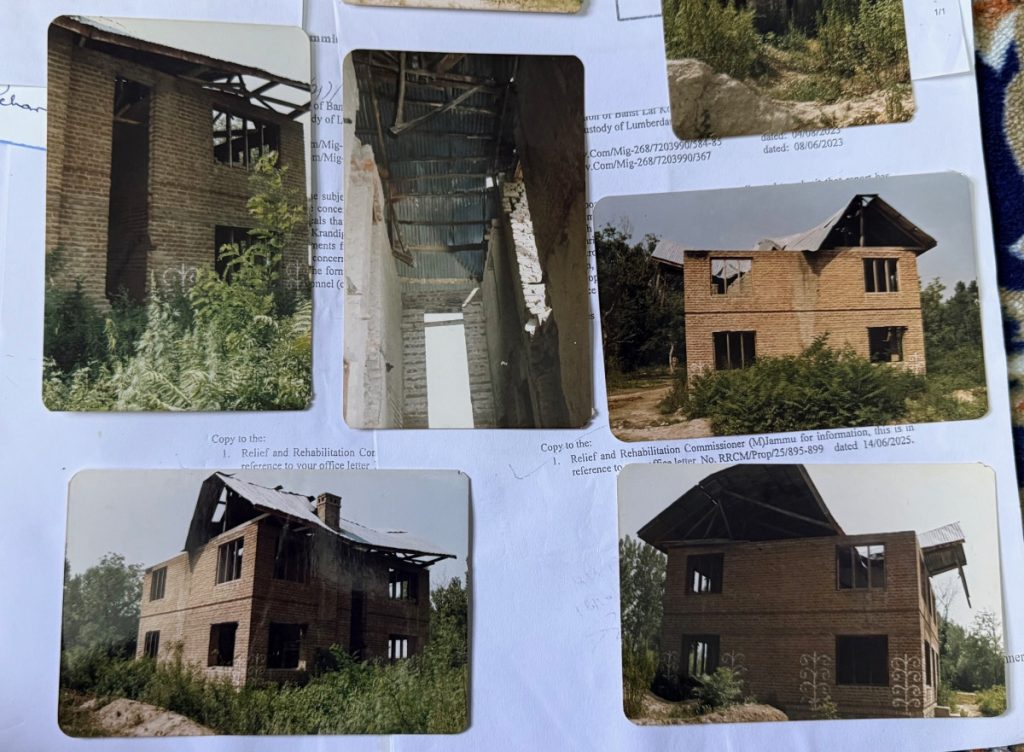

Koul’s complaints about his house in Bijbehara’s Laribal fill another, thicker folder. In the pictures Koul has collected over the years, the story unfolds chronologically: applications to district officials, damage assessment forms, photographs, duplicate affidavits, reminders, and re-reminders.

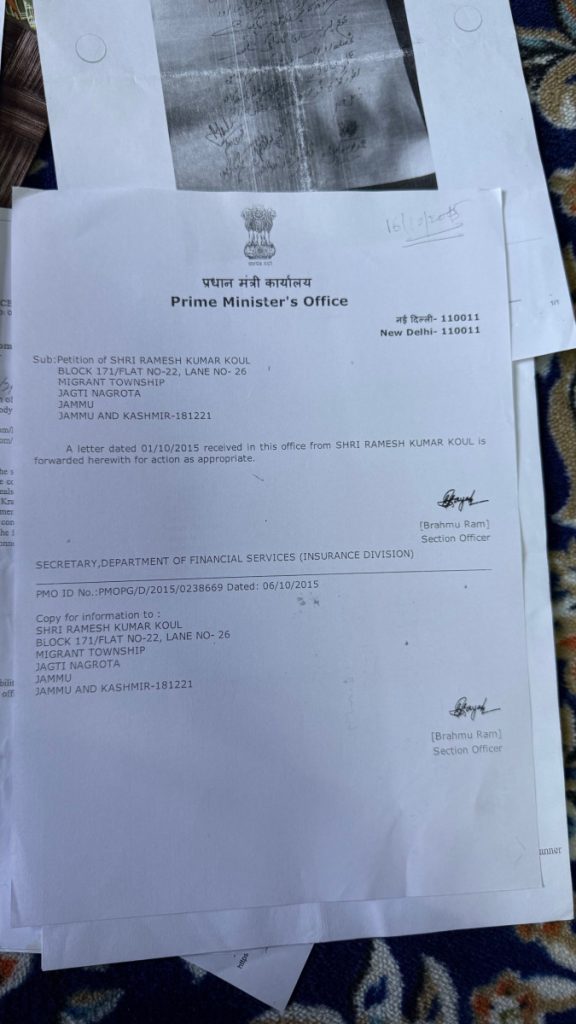

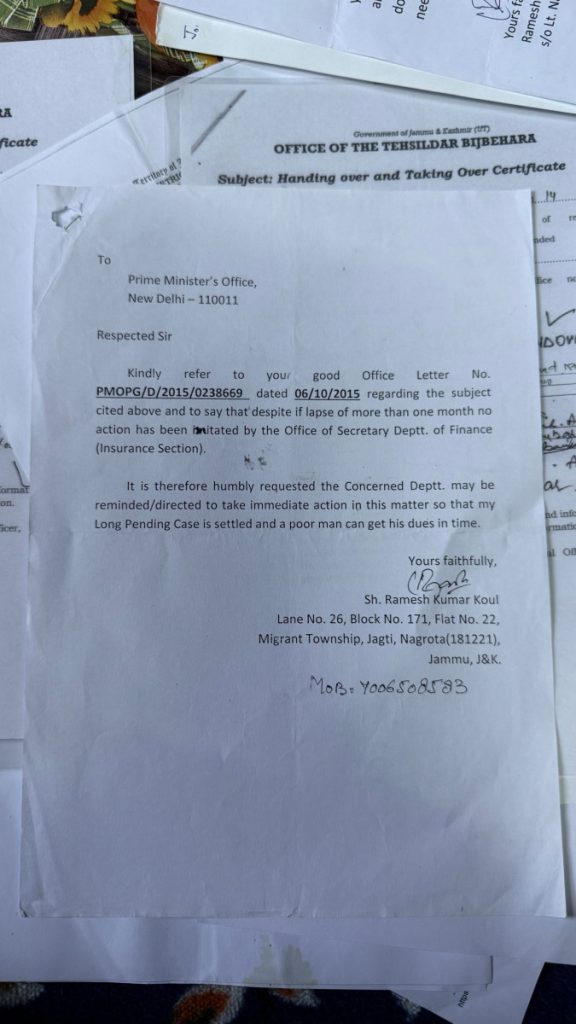

In October 2015, he penned a letter to the Prime Minister’s Office. The application was received by Brahmu Ram, a section officer at the PMO, who responded with a cold note: "application forwarded." Nothing followed.

The note acknowledging receipt of Koul's letter at the Prime Minister's Office in 2015. Photo: Tarushi Aswani

“Modi has used Kashmiri Pandits in every speech,” he says. “But when I wrote to him, nothing. I am still waiting.”

But when it comes to insurance, the earliest of his pleas are from the 2000s; the latest is barely a year old. Each repeats the same requests: restoration of his home, to act on encroachment complaints, to process compensation and update him on the status of his insured property. This bundle of requests and papers concerns the Oriental Insurance Company, the organisation with which Koul insured his home in Laribal.

While Koul’s home sat insured, he had to flee Laribal owing to the violence. But he kept paying his premiums on time, each of which has a receipt which he has held onto over the years. But in 2006, he came to know that his house was gutted in 1999. Koul ran to register an FIR at the local police station to strengthen his claim with Oriental. Then began a circle of endless letters, responses, delays and then finally, radio silence.

Photos of Koul's ancestral home taken in early 2000s. Photo: Tarushi Aswani

In one letter, he pleads for a field inspection. In another, he attaches photographs of the house, pointing out structural damage. In a third, he asks simply for “justice due to a migrant.” Each ends not with anger, but with exhaustion.

The documents he shared with The Wire include years of premium receipts, renewal slips, property assessment forms, correspondence asking for claim updates, copies of his migrant ID and ration cards. The premiums were collected without interruption. The payouts never came. “Oriental Insurance ate my premiums,” he says. “They took money every year. But when I needed the insurance, they said nothing.”

The stack of correspondence with Oriental at Koul’s home contains no approval letter, no inspection report, no transfer of compensation – only copies of his repeated attempts to follow up.

Later, he wrote to PM Modi about this, his office appears to have ignored it.

A followup letter Koul wrote to the Prime Minister's Office in 2015. Photo: Tarushi Aswani

The politics of the protection of Pandits

For a decade, Kashmiri Pandits have been central to the Modi government’s political vocabulary, with the party politically deploying symbols of a promise to restore what was lost. But Koul’s meticulously preserved papers cut through the rhetoric.

The state acknowledges him on paper and as political fodder. But the system does not act.

His agricultural land was restored after several letters but his house remains in a bureaucratic deadlock, his insurance claim was never processed and his letters to the PMO were never answered.

Also read: Away From Home, A Kashmiri Pandit Is Reviving His Language

“They talk about us as if they have saved us,” he says. “But what have they done for my home? My land? My future?” His is not the story of a spectacular tragedy but of a quieter suffocation: a citizen suspended in paperwork, trapped between promises made at podiums and a bureaucracy that refuses to move.

But back in Laribal, Koul’s neighbours and childhood friends have taken over the upkeep of his home and now-freed agricultural land. Ghulam Nabi, Koul’s childhood friend, remembers the days when they would play together near paddy fields. “The world might never believe us, but we really wish our Pandit brethren could come back and live in their homes like old times,” he told The Wire.

Another neighbour, Haji Abdul Rashid, who phones Koul to share each small or big feat of his, was deeply distressed when he visited Koul’s gutted home with The Wire.

Koul's neighbours in Laribal's Krandigam look at his ancestral home gutted in the 1990s. Photo: Tarushi Aswani

A pattern

Koul's documents illustrate a pattern of a state that uses the idea of the Kashmiri Pandit as a political emblem, while the actual displaced person stands unheard. They are proof of a government that promises protection but delivers acknowledgements and of a system that corrects errors only when cornered. Koul lifts the bag of papers, ties the fraying string around its mouth, and says: “The BJP government keeps telling the world they are safeguarding the rights of Pandits. But look at my life. Tell me, where is the justice?” Koul asks.

Jagti township houses around 5,000 families. Photo: Tarushi Aswani

Koul has lived in the Jagti Camp at Jammu for over 15 years now. “This is my second camp in the last 30 years, and even the relief that we get is miniscule. For months we have been protesting to get the relief amount increased from Rs 13,000 per family to Rs 25,000 per family. Is this not in the BJP’s control?” he asks.

Another Pandit at Jagti, Ashwini Bhatt feels sheer despair when he looks at the camp and the people who live in it. “When the displacement of Kashmiri Pandits happened, we were scattered across India. After some of them moved to tenements after the exodus, they were plagued by snakes and insects in them. Manmohan Singh [administration] concretised the tenements and we got these camps. We wanted permanent settlement since then and even today, people who came to power using our pain have done nothing to improve our living conditions,” Bhatt says.

Veerji, who has lived at both Jagti and Purkhoo camps, says that the fact that the Kashmiri Pandit community continues to live in camps even after they voted for the BJP is testament to the party's apathy. "We were promised return and resettlement. But we see no change, but only a spike in attacks on Hindus," he says. Others also added that return policies which are still in the nascent stages should not push Pandits to ghettoisation, rather they should aim at coexistence with Kashmiri Muslims.

Foundation stone of the Jagti township stands at the entrance of the block. Photo: Tarushi Aswani

The killings of government employee Rahul Bhat and schoolteacher Rajni Bala in 2022 have revived insecurity among Kashmiri Pandits who remained in the Valley or returned under employment schemes. Reports show that while the 1990s were a phase when the exodus began, since 2019, militants have increasingly singled out individual civilians, often in workplaces or near residential clusters. These attacks have led to protests by Pandit employees, demands for relocation, and renewed anxiety within relief colonies in Jammu.

Versions of Koul’s story are visible across Jagti – a man flipping through a torn folder of compensation forms, a woman holding on to an old photo of her damaged house in Shopian, and neighbours comparing which camp has more families occupying space. Most describe long stretches of waiting broken only by another round of paperwork.

For families who have lived in relief colonies for decades, this slow churn has become part of daily life. Policy discussions on return and rehabilitation continue in the background, but people here say they rarely know how those plans might touch their own cases. On most mornings in Jagti, Koul secures his stack of documents before stepping out to work or to an office counter that may or may not offer an update. “I’ve been waiting 30 years,” he repeats.

The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.