‘There Is No Air to Breathe’: Letters From Jaipur Central Jail Reveal Prisoners’ Fight for Basic Amenities

Mumbai: In the high-security cell of Jaipur Central Jail, Rizwan* must carefully consider when to use the in-built toilet. The cramped space that has been his 'home' for nearly three years is devoid of both ventilation and an exhaust fan. This means that once he uses the toilet, the stench gets trapped in the room, lingering for hours.

“It is unbearable,” he says. Rizwan continues to hold his breath for long periods, multiple times, as the small cell quickly transforms into a “torture chamber.”

Rizwan is one of over 50 'high-security prisoners' in Jaipur Central Jail. Both convicted individuals and pre-trial detainees have long raised complaints with jail authorities, trial courts and even the Rajasthan high court about the lack of basic amenities at the facility. These complaints, some dating back to 2019, have gone unanswered. Now, over a dozen incarcerated individuals have shared their complaints and written letters with The Wire, providing graphic accounts of daily life in the overcrowded jail.

According to data released by the state prison department in September 2024, the facility houses 1,818 prisoners when it was designed for just 1,173. As a fairly large central prison accommodating both pretrial and convicted prisoners, one would expect basic amenities for those incarcerated. However, several complaints, petitions, and letters reviewed by The Wire reveal that prisoners are denied even the most fundamental provisions.

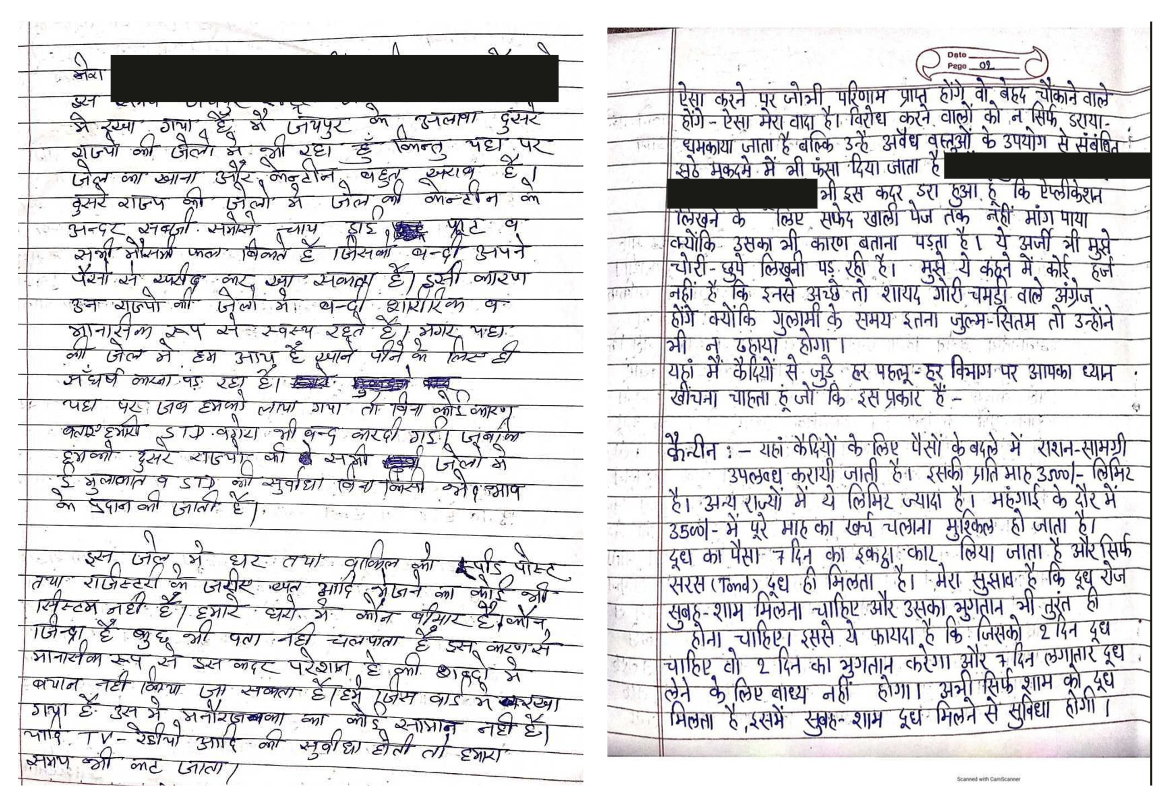

Excerpts from two of the several letter sent to The Wire. Photo: Sukanya Shantha

'A mug, a blanket and a can'

Wasim, who was convicted a few years ago in a terror-related case, explains the induction routine for a new prisoner. Upon entry, he says, prisoners are given one mug, one black-coloured blanket, and one can that holds five litres of water. “This is all you get to survive inside the prison,” he writes. For everything – bathing, using the bathroom and even storing potable water – this small can is all that is allotted.

Jaipur winters are particularly severe, and a single coarse blanket is all that prisoners are provided to both spread on the floor and cover themselves, Wasim writes in his 12-page letter. The dilapidated structure, crumbling ceilings and leaks in many cells, causes prisoners to live in constant fear of being crushed if the ceiling collapses. “Plaster falling into our food is an everyday occurrence,” he shares in his handwritten letter drafted in Hindi.

Most of the convicted prisoners who have written to The Wire have lived in prisons across Rajasthan; some even have trials pending in other states. In their letters, they claim to have a sense of the conditions in other facilities. For instance, Murari*, a pretrial detainee facing multiple cases, writes that after spending considerable time in various prisons across Rajasthan, he can say with certainty that Jaipur has the “worst facilities.” The food, he alleges, is of “poor quality,” and the only vegetable served for both lunch and dinner is cucumber. “Prisoners rejoice when aaloo (potatoes) and bhindi (okra) are accidentally served,” he writes.

In his letter, he also claims that Jaipur Central Prison is perhaps the only prison in the country that does not offer ‘wet rations.’ In most prisons, the food is of such poor quality that prisoners depend on canteen services available in the facility. But in Jaipur, unlike most other prisons, no cooked food items (referred to as “wet canteen”) are provided. The canteen, according to numerous prisoners, only offers basic snacks.

Access to the canteen is also an expensive affair and only those who receive regular money orders can avail the services. When families visiting incarcerated individuals carry snacks and home-cooked food, it is often not allowed inside the prison, a few prisoners allege in their letters.

'No privacy to speak to family, lawyer'

Another common problem faced in prisons is the lack of escort police to ferry prisoners to court for their regular hearings. These court visits, along with providing some fresh air to those in confinement, also allow prisoners to meet their family members more freely. But most prisoners are “produced” before the trial court only through video conferencing (VC) facilities.

Jaipur prisons have only three computers dedicated to VC and close to 200 persons are produced using the VC everyday. A prisoner, Dayal*, shares that their production via VC is merely procedural and they never get an opportunity to voice their grievances to the court. “Your face is shown to the judge and you are moved away,” he writes.

Dayal, lodged in the high-security cell, shares the routine humiliation and hardship his family members face when they visit him for the weekly mulaqat. Dayal’s family travels from a village in a distant district every week to meet him. “They arrive at the prison around 8 am but have to wait until 4 pm for their turn to meet me. This meeting too lasts no more than 15 minutes, under the surveillance of the prison staff,” he writes. If the jail has a VIP visitor, the family members are sent back.

In another instance described in a letter from another undertrial prisoner, he wrote that the lawyers who come for jail mulaqat also have to go through the same arrangement as the family members. This makes discussions and talks about legal strategies impossible. Lawyer Deeksha Dwivedi, who once represented a client lodged in Jaipur jail and later moved to Ajmer, confirmed the claims made in the letters. She says, “The mulaqat room for public and lawyers is the same. We have to stand across a glass screen and talk on the phone to our clients. There is no privacy; no client-attorney privilege can be maintained and at times people come and stand behind the prisoner to hear what he is saying to his lawyer.”

In a long letter, a copy of which was also sent to the chief justice of the Rajasthan high court, a prisoner complains that his letters do not reach the desired recipient. The letter is stopped at the prison level, he alleges. A similar concern is raised in a letter from a lawyer to his client lodged in Jaipur Central Jail, in which he writes, “I did not hear from you after my last letter. I am not sure if the letter even reached you.”

'Only well-educated prisoners have a problem': prison authorities

Overcrowding, a problem that the superintendent of the prison, Rakesh Mohan Sharma, also acknowledges, has been a serious concern. With the occupancy rate ranging between 150-160%, prisoners are cramped in already tight spaces. One young prisoner, in his letter to The Wire, described how over 100 people are lodged in his barrack. In that room, there is just one ceiling fan, he says. “There is no air to even breathe in this closed space,” he complains, adding that survival is particularly challenging in the summer and monsoon seasons. Prisoners from impoverished backgrounds, who don’t have money to buy a soap or bucket, often go days without a bath. “The stench in the rooms is unbearable. Many here complain of skin diseases.”

Also read: From Segregation to Labour, Manu’s Caste Law Governs the Indian Prison System

Multiple prisoners share their experience of being violently attacked, segregated and threatened with dire consequences for complaining about the inhuman living conditions in jail. While sharing their woes with The Wire, many of them explicitly mention that their letters will expose them to the authorities’ wrath, but they are willing to take this risk so long as their problems are made public and the state acts on them.

The Wire contacted Sharma with a detailed questionnaire. In response to the many allegations made by prisoners, Sharma said he wouldn’t comment but, in a generic sense, spoke about the “attitude” of those in prison. “They claim that their letters aren’t reaching their lawyers, but you have received their communication. So at least that one bit is clear: the prisoners here are able to stay in touch with the world outside.” However, these letters were not sent to The Wire through the postal service – the only legitimate medium of communication to and from the prison – available to the prisoners. Their inability to send or receive letters from their lawyers and family through the postal service continues to be a problem.

Sharma also claimed that these complaints arise only because the prisoners are “idle". “When you are busy for the entire day, you barely think about your food. The prisoners here are free to think about issues that should not really be a concern,” he said. He also claimed that there is a “peculiar category” of prisoners who complain about the state of the prison. "These are well-educated prisoners, who are part of an organised syndicate and have leadership skills." The superintendent, however, had nothing to add on the concerns raised in the letters, saying that “[it] is a matter of inquiry".

Sharma did, however, agree that overcrowding in the prison is a serious issue but said, “It is for the state to address this concern. I have limited resources, and with those resources, I try to do my best.”

*Names of incarcerated persons have been changed for anonymity.

This article went live on January fifth, two thousand twenty five, at forty-eight minutes past one in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.