UP Forest Dwellers Accuse Forest Department of Denying Them Their Rights

Bahraich (Uttar Pradesh): Sixteen years after the implementation of the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, only five forest villages have been granted the status of revenue villages so far and only 273 people have been given individual land rights in the Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary in Bahraich district, Uttar Pradesh.

Even though the five forest villages and 15 forest settlements in the area are inhabited by 2,383 families, the grant of rights to these forest dwellers under the Forest Rights Act (FRA) is moving at an extremely slow pace. In fact, the Forest Department has yet to recognise 14 out of 15 forest settlements in Katarniaghat as legal. The department claims that these settlements are encroachments on forest land and the tribals’ claim of residence in the area being three generations old is unsubstantiated. Based on this argument, the Forest Department has been taking action against these settlements time and again. Recently, residents of one of the settlements were issued a notice to vacate the area. In other forest settlements, the forest department creates hindrances in the implementation of important schemes like toilets, housing, drinking water and roads.

Putting down roots

Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary is spread over an area of 517 sq. km. Located on the Indo-Nepal border, this forest area comes under the Dudhwa Tiger Reserve and is adjacent to Nepal’s Bardiya National Park. Two tributaries of the Ghaghara river – Girwa and Kaudiyala – flow through the forest, which is mainly covered by sal or sakhu trees and tall grass. It is the natural habitat of tigers, leopards, rhinoceros, deer, alligators and crocodiles. Gangetic dolphins are also found in the Girwa river.

The Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary. Photo: Manoj Singh

The forest villages and settlements under Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary have a history dating back more than a century. According to the forest dwellers, their forefathers were settled here by the British to carry out sal plantation, cut and transport trees and as forced labour for the officers.

The work of preparing sal forests using the taungya method (the system in which plantation workers are given the right to cultivate crops while the forest is still being established) began in 1922. In 1925-26, tree plantation using the method was first introduced in the Motipur range by making Mehboob Nagar, Nazir Ganj and Tara Nagar taungya centres. Later, tree plantation was carried out in the whole of Katarnia and the practice continued till 1984. During this period, forest villages and settlements were moved according to the needs of plantation work. After 1984, the Forest Department stopped employing forest dwellers to plant trees and made attempts to evict them from the forest. But the forest dwellers who had been living there for more than 50 years refused to leave their villages.

Also read: Environment Ministry’s New Forest Diversion Rules Are Bad News for Forest Rights

In 2005, a few social activists launched a forest rights movement by uniting forest dwellers. At that time, the forest dwellers did not even have the right to vote nor build a pucca (concrete) house and had no access to ration cards, copies of the family register (the document that tracks the information of a family-centric legal interest), schools, or anganwadis (child care centres). No matter how educated the youth in the villages were, they could not find jobs in the absence of a residence certificate. However, many activists leading the movement including Jang Hindustani, president of the Sevarth Foundation, Saroj Gupta, Farid Ansari and Samiuddin Khan, were booked and jailed for 40 days. Cases are pending against many of the activists even today.

The situation changed after the Forest Rights Act came into force in 2006. Forest dwellers put forward their individual and community claims by forming Village Forest Rights Committees, but these claims were rejected at various levels. In 2019, 13 years after the implementation of the Act, an order was issued to convert Gokulpur into a revenue village – a status that gives the residents access to government schemes – and in January 2022, four forest villages – Bhawanipur, Bichia, Tedia, Dhakia – were also granted revenue status.

Status of the FRA

There are five forest villages in the Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary – Bhawanipur, Bichia, Dhakia, Tedia and Gokulpur. One forest village, Jamuniha, was displaced by the Forest Department long ago and the displaced population is currently settled in Dhanaura Tanda Karikot.

In addition, there are 15 forest or vantaungya settlements – Mehboob Nagar, Srirampur, Sukhdipurwa, 2755, Rampur Ratia, Dharampur Ratia, Sampatipurwa, Tulsipurwa, Haldiplat, Jagapurwa, Kakraha, Murtiha, Bichiya, Nishangara and Katarniaghat. Under the Fixed Demand holdings in Bichia, people were allotted forest land on annual lease for housing and shops. The farming community among them were given forest land for cultivation in the village on the other side of the station.

At present, the vantaungya of forest villages and settlements have 2,383 families in all, with a total population of around 13,000. There are more than 6,000 people in the five forest villages while 7,000 people inhabit the forest settlements.

The Rampur Ratia forest settlement. Photo: Manoj Singh

All the five forest villages have now been granted the status of revenue villages. While Gokulpur was first converted into a revenue village on November 28, 2019, the remaining four forest villages – Bhawanipur, Bichia, Dhakia, Tedia – were granted the status on January 7, 2022.

Some of the 15 forest settlements located in the Katarniaghat Sanctuary, such as Rampur Ratia and Dharampur Ratia, have a large population, while others like Kakraha and Murtiha have just one family and nine families respectively.

Also read: UP: In the Face of Oppression, Eviction, Vantangiyas Continue Century-Old Fight for Land Rights

Out of the 15 forest settlements, the claim verification of 274 families of only one settlement, Mehboob Nagar, has been completed so far. The task of preparing a family register has also started here. In all the remaining forest settlements, Village Forest Rights Committees were formed in 2019 and the process of the forest dwellers’ claim submission is underway. Due to the sluggish pace of work at various government departments, including the Social Welfare Department and the Forest Department, the process of verifying and pursuing forest rights’ claims is moving slowly. In some cases, the forest dwellers have not even been given claim forms and residents are managing by photocopying the original form.

A house in Rampur Ratia. Photo: Manoj Singh

In the forest villages of Bahraich district, only 273 individual claims have been accepted so far. Out of these, authorisation letters have been granted to 93 forest dwellers while 180 letters are yet to be distributed by the administration. Meanwhile, the subdivision level committee rejected 895 claims.

The people whose individual claims have been approved have not yet been issued their khatauni (legal land records), due to which they are unable to avail several government schemes, and banks facilities.

So far, no individual and community claim has been accepted under the Forest Rights Act in 15 forest settlements of the district. The Forest Department considers these settlements unauthorised encroachments and carries out eviction drives, harasses residents and frequently issues them notices.

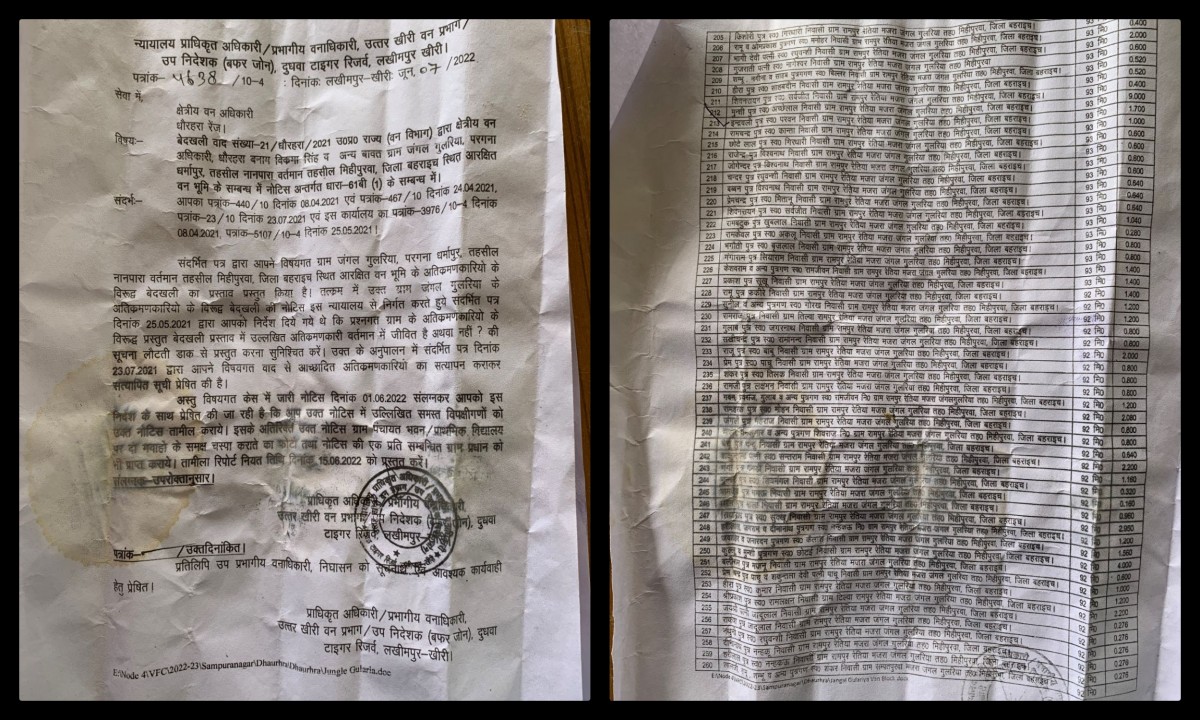

The notice sent to inhabitants of Rampur Ratia. Photo: Manoj Singh

Radheshyam, secretary of the Village Forest Rights Committee, said that 53 individual claims have been approved in Gokulpur, which has been declared a revenue village, while 40 claims are pending at the subdivision level. The acreage of those whose claims have been verified has not yet been recorded in the khatauni. The village has a pucca road and a power supply. There is a primary school but no anganwadi. Six forest dwellers have been issued houses under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (housing scheme) and toilets have also been constructed for about a dozen people.

However, no development work has started in the four revenue villages as yet, other than in Gokulpur.

Contradictory actions

Ram Bahadur's son Kamta, a resident of Tedhia village, received a housing fund under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana. When he started building the house, forest department officials arrived and asked him to stop the construction. He was later summoned to the forest department’s office and arrested under the Wildlife Protection Act. He was released from jail after three months.

Ram Bahadur told The Wire that he was sanctioned Rs 1.20 lakhs for the construction of a house under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana. After receiving the first installment, when he started building the house in December 2019, the forest department officials told him that ‘Ranger sahib has denied permission for any concrete construction in the area’ and asked him to halt the work immediately. The officials left him with a warning. However, when Ram Bahadur continued the construction work, he was called to the forest post in Ghosiana, and arrested.

A case was registered against him under Sections 26 of the Indian Forest Act, 2/3 (a) of the Forest Conservation Act, and 27, 29, 31, 39, 51, and 52 of the Wildlife Protection Act.

Ram Bahadur. Photo: Manoj Singh

Ram Bahadur was not even told what his crime was. “Those officials have a pen in their hands and write whatever they want. What can we do?” he said. He is still scared by what happened and feels that the forest department might act against him again.

Denial of toilets

Sukhdipurwa has around 55 families, all of whose ancestors worked on sal plantations in both colonial and independent India. Presently, this village is affiliated with the Sujauli Gram Panchayat. A Village Forest Rights Committee has been formed here, headed by Ram Nagina and with Raghuveer as its secretary. The committee is carrying out the work of claim verification in the village.

Also read: Has the J&K Administration Completely Misunderstood the Forest Rights Act?

The Forest Department considers this forest village illegal and calls these forest dwellers encroachers. Two years ago, some women residents of the forest village – Prabhavati, Reena, Reshmi, Meena, Sunayna, Rukmini and others – each received Rs 12,000 for the construction of toilets under the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan. When the locals brought in bricks for the construction, the forest department officials stopped the work. The residents claim that even though they had been granted permission for toilet construction under the government scheme, not a single toilet has been built in the village. The forest department is not allowing the forest dwellers to build toilets even with their own resources.

Women in the Sukhdipurwa forest settlement. Photo: Manoj Singh

A dozen people in the village were also allotted housing funds under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana in 2015-16, but the beneficiaries did not receive the amount because the Forest Department created obstructions.

According to a local villager, Shankutala Devi, the lack of toilets create major problems during the rainy season due to water-logging. There is also the fear of attack by wild animals while incidents of snakebite increase in the monsoon. But the forest department pays no heed to the villagers' needs.

Villagers Prabhunath Chauhan, Kamlesh Chauhan, Shakuntala, Ramshankar, Vijay Kumar and Harendra Kumar told The Wire that the forest department is not even allowing the construction of a pucca road to connect the village to the main road. When the forest dwellers tried to repair the kutcha road themselves, the forest officials stopped the work. Rajkumar, Ramchand, Nandlal and Ramsaran claim that they have agricultural land on which they grow paddy, wheat and sugarcane, but do not get the benefit of any government scheme for farmers because in the records, their land belongs to the forest department. Nandlal said that he has not yet received Rs 2,000 under the PM Kisan Samman Nidhi scheme.

In this forest village, residents have only got solar lights in the name of the government’s development schemes. There are only three India Mark II hand pumps for drinking water with which the locals are somehow managing. The village was also to be brought under the purview of the government's Har Ghar Nal Se Jal Yojana (piped water in every house scheme) for piped water supply, but due to the objections of the Forest Department, the scheme could not be implemented.

Threat of eviction

Rampur Ratia village falls under Gularia forest along with two other villages, Dharampur Ratia and Sampat Purwa. Rampur Ratia is in Bahraich district, but comes under Dudhwa National Park.

On June 7, 2022, 341 village residents got a notice from the court authorised officer, the divisional forest officer, North Kheri Forest Division, and the deputy director, Buffer Zone, Dudhwa National Park. Only after they received this notice did they learn that proceedings for their eviction are underway in the court at Dudhwa Tiger Reserve, Lakhimpur Kheri, under Eviction Case No. 21 Dhaurhara/2021 Uttar Pradesh State (Forest Department).

The notice states that Gularia is reserved forest land and the people living on it are encroachers. The oldest resident of this village, 90-year-old Jangalee, said that no such notice had ever been served to the villagers before. His father and grandfather worked at a plantation here while he himself had planted a rosewood forest in Dhania Beli and worked as a labourer for the Forest Department. “Our forefathers lived and died in this very forest and now we’re being termed encroachers. It is very shocking,” he said.

Jangalee. Photo: Manoj Singh

The secretary of the Village Forest Rights Committee, Shyam Bihari, said, “The forest dwellers living here have filled up individual and community claim forms and the committee has verified them. We were about to send it to the Block Level Committee when this notice arrived.”

Shyam Bihari said that village head Mukesh Kumar has written a letter on behalf of the residents to the prime minister, the chief minister and the divisional forest officer about the notice, demanding an end to the eviction proceedings.

“As per the Forest Rights Act, we belong to the Other Traditional Forest Dwellers category. We have been living here for over 100 years. Under the Forest Rights Act, we should get the authorisation letter on our residential and agricultural land, but instead, efforts are being made to evict us,” he said.

Clause 4 (5) of the Forest Rights Act clearly states that the forest dwellers cannot be evicted without completing the process of verification and recognition, but the forest officials are ignoring it.

The village, situated near Ghaghra river, is also a flood prone region. During the past few years, the river’s course has diverted towards the village, said Jangalee. Two years ago, Chahalwa and Dharampura were inundated and the population in both the villages was displaced. The villages have not yet been rehabilitated.

“If the erosion in the river continues and no measures are taken to prevent it, then our village might also be displaced,” he said. “While on the one hand, the forest department is trying to evict us, on the other hand, we face the threat of river erosion. We are not getting help from anywhere.”

Bulldozer treatment

Suresh Jaiswal, a resident of Kakraha settement, lived with his wife and son Ankit Jaiswal in a makeshift tin shed near Kakraha railway station for a long time. He also ran a sweet shop in the shed. Suresh suffers from a kidney disease and goes to Lucknow for treatment. On June 23, forest department officials arrived with a bulldozer and dismantled their tin shed home. His son Ankit was beaten up for protesting.

Suresh Jaiswal was not given any prior notice regarding the demolition. He said his ancestors had come to work as vantaungya labourers in 1914-15 and had settled down after being allotted land in Kakraha, which has now been recognised as a forest settlement. It has a Village Forest Rights Committee which made claim forms available to the forest dwellers. Despite this, his home was demolished by the Forest Department.

Suresh Jaiswal in front of his demolished home. Photo: Manoj Singh

Ankit said that the house was demolished in the rainy season and the family was left without shelter. They are somehow managing with tarpaulins. He had got married on June 5, a fortnight before the bulldozer arrived, and his wife was terrified by the demolition of their house. He has left her at her parent’s house because they have no place to live. The family somehow managed a daily meal with their meagre earning from the sweets shop. But that support has been snatched away too.

Residents of these forest villages and settlements in Bahraich are forced to deal with persecution on a daily basis. Jang Hindustani, a social worker who has been working among the forest dwellers for more than 15 years, said that on June 1, before Suresh Jaiswal's house was demolished, Balakram and Ramlakhan Yadav of Bhawanipur forest village were arrested by a senior officer of the forest department when he found their cattle grazing in the forest. They were charged for grazing their cattle in prohibited area.

On receiving information about the incident, Jang Hindustant contacted the divisional forest officer of Katarniaghat and told him that Bhawanipur forest village had been converted into a revenue village under the Forest Rights Act and forest dwellers can graze cattle under community rights. After this was pointed out, the proceedings against Balak Ram and Ramlakhan were quashed and they were released.

Akashdeep Badhawan, the divisional forest officer, Katarniaghat said that Mehboob Nagar is a taungya settlement and the process of granting rights to the forest dwellers living here has been started.

“There is no evidence of the remaining forest settlements having been inhabited for more than 75 years. These settlements have also not been seen in the satellite survey. Some settlements came up after the enactment of the Forest Rights Act. That's why we consider them encroachments. This is why pucca work is not permitted there,” he said.

Manoj Singh is the editor of Gorakhpur Newsline.

Translated from the Hindi original by Naushin Rehman.

This article went live on August twenty-third, two thousand twenty two, at zero minutes past two in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.