From Karachi To Bay of Bengal, How the Indian Navy Played a Stellar Role in the 1971 War

The year 1971 was marked with several ‘big victories’ – in politics, cricket and in war – all of which had long term implications for India. The national mood was buoyant, even if the country continued to struggle with endemic problems.

Fifty years later, we look back at those times and evoke some of that mood. In a series of articles, leading writers recall and analyse key events and processes that left their mark on a young, struggling but hopeful nation.

As a freshly-minted naval aviator, I greeted the dawn of 1971 with mixed feelings. After a heady year of flying from INS Vikrant, I had been deputed to the Indian Air Force (IAF) for a two-year ‘exchange posting.’ I reported to my new squadron, based in Hindon, a thousand kilometres from the sea, feeling like a fish out of water. However, my IAF squadron mates, extended a warm welcome and made me feel quite at home. Hindon was only half an hour’s drive from Delhi, and despite petrol hitting a ‘high’ of Rs 1.10 a litre, we made to town often.

As 1971 wore on, the crew-room chatter, invariably, veered to happenings in East Pakistan. We watched, initially, with schadenfreude, and then with concern, as Pakistan, riven by political and ethnic differences between its Punjabi-dominated western wing and its Bengali eastern wing, marched inexorably towards civil war. A massive exodus of East Pakistani refugees, had created a social and economic crisis for India, and it fell to prime minister Indira Gandhi to craft a grand strategy which would halt the Pakistan army’s genocidal rampage and reverse the refugee influx.

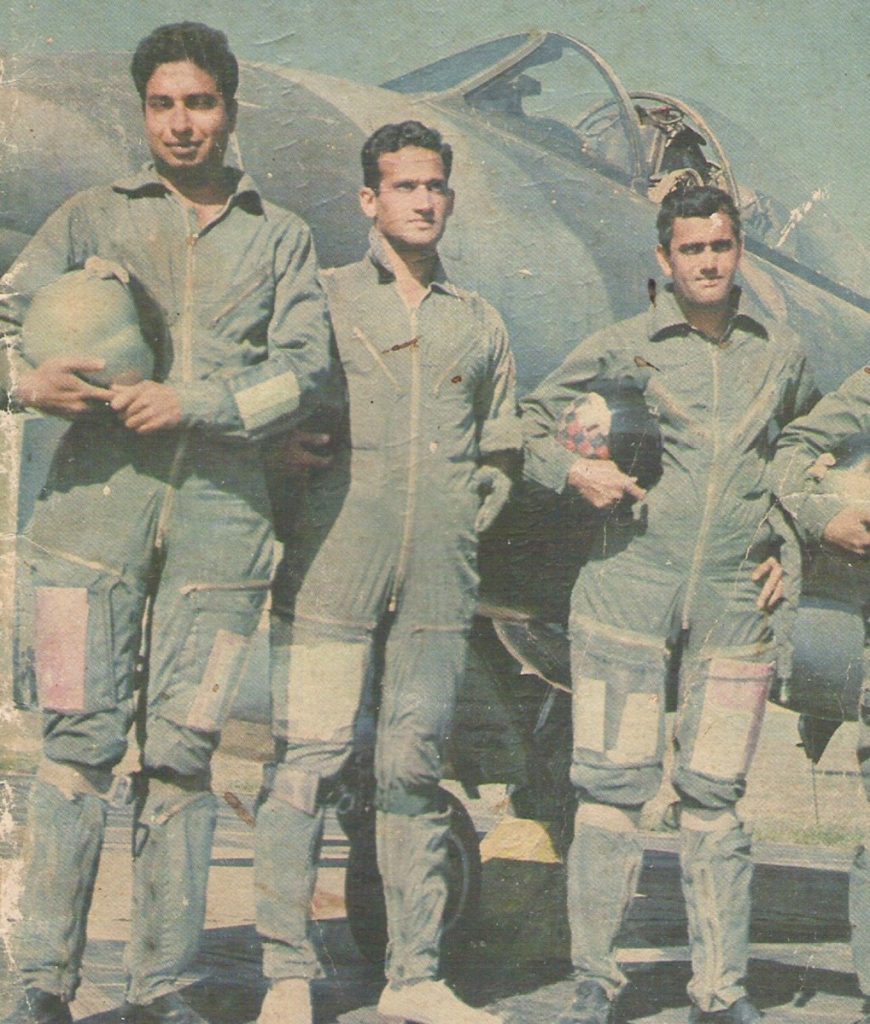

Arun Prakash with the Indian Air Force in 1971. Photo courtesy: Arun Prakash

At midnight on December 4, 1971, we were huddled around a transistor radio, as Mrs Gandhi announced: “I speak to you at a moment of grave peril … soon after 5:30 pm on 3rd December, Pakistan launched full‐scale war against us… Emergency has been declared for the whole of India.” Early next morning, we were winging our way to targets in Pakistan.

The ignominy of 1965

This preamble was to explain my absence from the navy, whose role, during the Bangladesh War, I am about to recount. But the roots of the brilliant 1971 maritime campaign go back to the severe discomfiture of the Indian Navy (IN) during the 1965 war, when I was at sea, serving as a midshipman, on Vikrant, till she went into drydock in June, and thereafter on the anti-submarine warfare (ASW) frigate Kirpan.

Thus, on September 6, I read the NHQ signal, informing the Indian fleet that war had broken out with Pakistan, and a few hours later, its baffling cancellation. On the night of September 7/8, we heard about a Pakistan Navy task force bombarding the town of Dwarka on the Gujarat coast and retiring with impunity.

On September 10 and 17, the fleet sallied forth from Mumbai, for wide sweeps to the northwest, in the hope of bringing the Pakistan Navy to action. In the absence of a tanker, we had to turn back when ships ran low on fuel. With Vikrant out of action, only sparse air effort was available to the fleet commander, depriving him of aerial reconnaissance, anti-shipping strike and airborne-ASW. False submarine contacts, led to many depth-charges being expended, and jittery radar operators caused ships to fire at each other, and at airliners passing overhead. But we found no enemy at sea.

It was only when we returned to harbour on September 23, in time for the ceasefire declaration, that we learnt of the unreasoned government directive, ordering the navy not to permit its units north of the latitude of Porbandar; a clear indication of the lack of maritime awareness at the political level. This, then, was the ignominy, from which the IN felt compelled to redeem itself.

Within six years, fortune was to offer the IN an opportunity to redeem itself, and the Bangladesh war saw the service being truly blooded in action. A bold and imaginative leadership exploited the full gamut of maritime capabilities. Space permits me to highlight only a few vignettes of the navy’s exploits that served to lay the ghosts of 1965 and demonstrate, to sceptical decision-makers, the navy’s potential as a powerful instrument of state policy.

Fire from the skies

Pride of place in the navy’s achievements of 1971 must go to two operations, code-named ‘Trident’ and ‘Python.’ In early-1971, India inducted 8 Soviet Osa class boats, armed with Styx, radar-homing anti-ship missiles. With limited endurance, these small boats were designed by the Soviets for a harbour-defence role, but IN conceived the bold plan of towing them across 250 miles of open seas and launching an attack on the Pakistan Navy, in its bastion.

Operation ‘Trident’ was launched on the night of December 4/5, when three missile boats, escorted by two corvettes, attacked Karachi, sinking the destroyer PNS Khaibar, minesweeper Muhafiz and a merchant ship. Operation ‘Python’ followed on the night of December 7/8, when another missile boat, escorted by two frigates, launched four missiles at Karachi harbour, damaging the tanker, Dacca, sinking a merchant ship and setting ablaze a huge fuel tank farm.

Apart from the material and psychological damage inflicted, the IN succeeded in bottling up the Pak navy in Karachi, with merchant ships seeking ‘safe passage’ from Indian authorities.

An Indian Killer squadron missile boat that participated in Operation Trident. Photo: Indian Navy, GODL-India via Wikimedia Commons

The ‘lame duck’ carrier

INS Vikrant having been rendered hors de combat [out of combat], in 1965, due to an ill-timed refit, the navy was determined that the carrier should make a major contribution, in the forthcoming conflict. But there was a serious catch.

The ship’s World War II vintage steam boilers had developed cracks and were badly in need of repairs. High-pressure steam from the boilers not only drove the ship’s engines, but also the ‘catapult’ that launched aircraft. If pushed too hard in their precarious condition, they could simply blow up, but we had, neither the spares nor the time for repairs. After much agonising, NHQ decided that Vikrant, with all its limitations, would go to war – but in the Bay of Bengal.

Vikrant’s two air-squadrons – one of Sea Hawk jet-fighters and the other of Alize turbo-prop ASW aircraft – played havoc with airfields, ports, merchant shipping and riverine traffic. With Vikrant blocking seaward escape routes for Pak forces, it hastened their surrender. The story of Vikrant’s, highly successful, operations off the coast of East Pakistan, abounds with instances of personal bravery, engineering ingenuity and outstanding leadership and resolve. Destruction of PNS Ghazi, which was sent to sink the Vikrant, proved the old adage that, ‘luck favours the brave.’

Vikrant's Sea Hawk squadron ashore during the December 1971 Indo-Pakistan war. Photo: Indian Navy, GODL-India/Wikimedia Commons

Underwater warfare

The submarine arms of both navies were actively deployed in 1971, but there was a contrast in the conceptual approach to operations. NHQ had taken a conscious decision that the IN would not undertake ‘unrestricted submarine warfare,’ and Indian submariners had strict orders to obtain ‘positive identification’ of targets before attack. Deployed off Karachi and the Makaran coast, for weeks, this impracticable proposition must have been a source of frustration for our submariners.

Pakistani planners, on the other hand, having made an early decision regarding the offensive deployment of submarines, sailed the Ghazi in mid-November, on a 3000-mile voyage, tasked to find and attack the Vikrant. PNS Hangor and sister Mangro, were sailed a week later, to attack targets of opportunity off Saurashtra and Bombay. Fate dealt with them differently; while Ghazi sank, with all hands, off Vishakhapatnam on the night of December 1/2, due to an internal explosion, Hangor, was able to torpedo and sink the frigate INS Khukri, off Diu on the night of December 10.

Special operations in East Pakistan

In addition to the intense aerial campaign and a naval blockade of East Pakistan, the IN also mounted a covert ‘Operation X’ whose full details have emerged only recently. Orchestrated by NHQ’s Directorate of Naval Intelligence, the operation involved the training of over 400 Mukti Bahini volunteers in activities like combat-swimming, diving, demolition and sabotage, at a secret riverside facility, for clandestine activity behind enemy lines in East Pakistan.

The operation also employed a small force of IN and Mukti Bahini gunboats to attack Chalna, Khulna and Mongla harbours and other targets on the Pussur River. In an unprecedented and heroic effort, the Indian and Bengali naval commandos destroyed nearly 100,000 tons of shipping in the rivers and seaports of East Pakistan, leaving Pakistani troops demoralised and woefully short of riverine transport to support operations in a guerrilla-infested territory.

The captain goes down

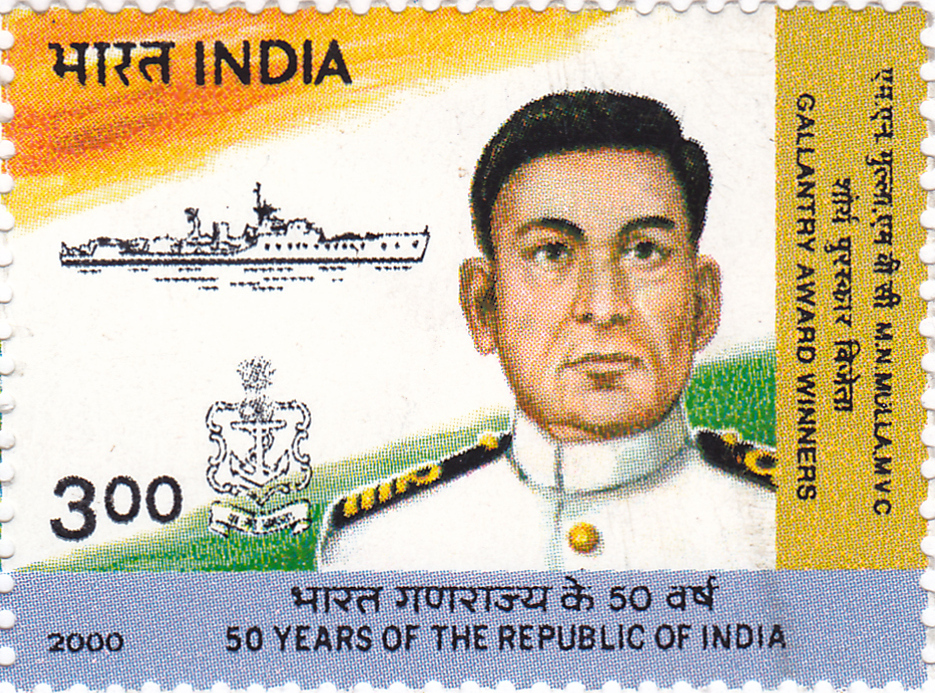

The loss of the frigate INS Khukri while on an anti-submarine mission, on December 9, was a sad blow for the IN, and yet, no account of the 1971 war can be complete without a mention of the fortitude and bravery of its commanding officer, Captain M.N. Mulla, who was awarded the Maha Vir Chakra posthumously.

Captain M.N. Mulla on a postal stamp issued in 2000. Photo: India Post, Government of India, GODL-India via Wikimedia Commons

The cat-and-mouse game between ship and submarine is always loaded against the former, but in this case, the match between PNS Hangor, a state-of-the-art French submarine, commissioned in 1970, and the 13-year-old Khukri was even more unequal. High speeds and evasive tactics could have provided protection to the ship, but ironically, these options were denied to Captain Mulla because his ship was undertaking urgent trials of a secret modification meant to enhance detection ranges of its sonar!

So, when Hangor’s torpedo exploded under the Khukri’s keel, the frigate had no chance of survival, and Mulla, gave the order to ‘abandon ship.’ Having ensured that as many of his crew as possible, had left, he resumed the Captain’s chair on the bridge, and calmly went down with his ship.

“Not because it was expected of him, or tradition required it of him,” says his daughter, Ameeta Mulla-Wattal, “but because, for him, it was the only thing to do.”

Admiral Arun Prakash (retired) is former navy chief.

This article went live on April fifth, two thousand twenty one, at forty-six minutes past two in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.