Politicising the Armed Forces Has Consequences

The climax of the recent Anantnag tragedy was written in 2014, when the Narendra Modi government formalised counterterrorism as the Indian Army’s primary task.

Well before it came to power, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was clear that tasking the army to do only counter-terror operations in Jammu and Kashmir would meet two of its important objectives.

First, it would cast Pakistan as a perpetual enemy, occupying both the army and the civilian population’s attention.

Second, by allowing Pakistan to function as shorthand for Muslim, the party would keep its core vote bank – Hindutva supporters – consolidated. This would help it in putting in motion its agenda of pushing for a Hindu rashtra. Since the Army would be lauded for its successes against terrorists, catapulting it to the centre stage of national imagination, it would not be able to resist being used for the political objectives of the ruling party. Moreover, to garner the support of the veterans, the implementation of the 'One Rank, One Pension' scheme was also announced.

Since the 13-lakh Army’s Order of Battle (ORBAT) or strength is around manpower, and nearly 50,000 soldiers join the rank of veterans each year, it was necessary to keep them aligned with the ruling party’s ‘nationalist’ thinking where perception (enhanced by a complicit media) would matter more than reality. The Air Force and Navy, whose ORBATs are around its combat platform would, with fewer manpower, follow the Army’s lead for personal glory and gratification.

Making the armed forces fall in line

With this as the backdrop, the Modi government quickly got to work on its agenda of aligning the Army (and military) to its political requirements. This was made possible in four successive steps.

One, within weeks of coming to power, defence minister Arun Jaitley praised the army’s CT ops in Rajya Sabha on July 22, 2014 and suggested that the fence on the Line of Control (LC) be upgraded. Encouraged by this, the then-Nothern Army commander Lt General D.S. Hooda told the media in August 2015 that the fence would be strengthened by state-of-the-art sensors for surveillance.

Fencing of the active LC in July 2004 by army chief General N.C. Vij was the Army’s biggest mistake. It instilled the Maginot mentality (defensive mindset) in the troops. Any worthwhile military commander the world over will attest that a fortification induces a false sense of security and stifles the attacking spirit of an army. Thus, on the one hand, the fence gave assurance to the Pakistan Army to continue with its peacetime training for war without worrying about Indian retaliation in the form of raids on their posts – which was a common activity by both sides in the 90s. On the other hand, the initiative passed completely into the hands of terrorists and their handlers across the military line. The latter dictated the rates of engagement, infiltration, areas to be activated and to what purpose, including methods of initiation.

Throughout the nine-year tenure of defence minister A.K. Antony under the Manmohan Singh government, there was a debate to dismantle the fence and progressively end the army’s role in CT ops. Nothing came out of it since an indecisive Antony supported the army’s viewpoint to continue with CT ops which gave it awards, honour, status, and perks, including total authority in the state of J&K. The 15 corps commander in Srinagar could ride roughshod over the elected state chief minister.

With the Modi government formalising CT ops as the Army’s primary role, that Damocles’ sword hanging over the Army leadership’s head was lifted.

Two, addressing his first combined commander’s conference in Delhi in October 2014, Modi gave his threat assessment to the military leadership. In professional militaries, its leadership and not the prime minister determines the external threats facing the nation. But under the new political dispensation in India, Prime Minister Modi told the military that ‘the threats may be known, but the enemy may be invisible.’ The ‘threat’ was Pakistan, and the ‘enemy’ was the terrorists, who are faceless, nameless, and dispensable.

The Army gladly agreed to continue with CT ops in Jammu and Kashmir. Not to be left behind, Air Chief Marshal Arup Raha told the media in December 2016: "We must focus on deterring terrorist attacks or fighting the sub-conventional threats. We are training large number of personnel for this role. We are tweaking our tactics and are looking at equipment for this role."

The China factor

Sadly, the armed forces were unmindful of what the People's Liberation Army (PLA) was doing along the shared military line (Line of Actual Control) at that time. For example, in 2014, the PLA declared its new military strategy (which was as transformational as Mao’s 1956 military strategy) with three peculiarities: maritime (naval) domain was mentioned for the first time; three new war domains, namely outer space, cyber, and electromagnetic, were added to the physical ones of land, sea, and air; and a new war concept of joint integrated operations called informatised war was announced. To consolidate informatised war, the PLA in 2015 declared its biggest military reforms to be completed in five years – under which it created the Western Theatre Command (its largest land command) for war with India.

Interestingly, alarmed by PLA’s rising capabilities, the Pentagon, in 2014, announced its third offset strategy underpinned by Artificial Intelligence and autonomy to offset the former’s operational advantages.

A photograph released by PTI shows Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) soldiers reportedly near the Indian post near Mukhpari peak in Ladakh on September 7, 2020.

Three, the Modi government has made a purely military issue of Pakistan’s cross-border terrorism into J&K into its political redline for improving relations with Pakistan. External affairs minister S. Jaishankar has repeatedly said that ‘it is not possible to have a normal relationship with Pakistan until there is a departure from the policy of cross border terrorism.’

Cross-border terrorism is a common military strategy used to fight an enemy with larger numbers. For instance, the Pakistan Army has half the numbers as compared with the Indian Army’s 13-lakh strength. In this strategy, without inducting its own soldiers in combat, the enemy uses terrorists to weaken the other side’s regular army by (a) unabated CT ops, and (b) keeping it away from its primary task of preparing for conventional war which requires regular training in Combined Arms Operations (CAO). That CT ops and CAO are as different as chalk and cheese has been proved twice before – during the 1999 Operation Vijay (Kargil conflict); and later during the 2001-2002 Operation Parakram (after the attack on India's parliament).

During the Kargil conflict, the commander of the 8th Mountain Division Maj0r General Mohinder Singh said that it took him weeks to reorient his troops doing CT ops to fighting the conflict. And, during Operation Parakram, the northern army commander Lt General Rustom K. Nanavati had sought six months’ time from the army chief General S. Padmanabhan to orient his forces from CT ops to conventional war; it was good that the Vajpayee government decided not to go to war.

Ways of ending cross-border terror

There are two ways of ending Pakistan’s cross-border terrorism. The first is for India to start meaningful talks with Pakistan; once this happens, the Pakistan Army will control the terrorist flow into Kashmir. According to Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri, who was Pakistan’s foreign minister from 2002 to 2007 under the Musharraf regime, "In 2005 and 2006, I started hearing in hushed tones at the Presidency and in some other high-level meetings that centres had been set up to wean away militants from their past and impart skills to them which would help them integrate better in society." In this period, backchannel peace talks were happening between India and Pakistan which eventually led to Musharraf’s four-point formula for peace in the region.

The other way is for the Indian military to build credible deterrence (warfighting capability) which would force Pakistan to review its misadventure lest it boomerangs. In 33 years, since 1990, the Indian Army leadership has preferred to get its soldiers killed in CT ops rather than prepare itself credibly to defeat the Pakistan Army. This, unfortunately, suits both the Army leadership and the Modi government which has demanded that Pakistan cease cross-border terrorism, while adding that the only issue to discuss bilaterally is the return of Pakistan Occupied Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan to India. It suits India not to have normal ties with Pakistan.

And four, the government deftly co-opted the mainstream media to carry forth its political agenda to the masses through the relentless broadcasting of the party-approved narrative. This has been made possible through the triple combination of allurement, punishment and ideological convergence. By conflating nationalism with patriotism and criticism of the government with anti-national activities, the government facilitated the collaboration of the retired military officers and the media for this purpose. After all, who could be a bigger nationalist than the military which sacrifices itself for the nation?

A consequence of this was that any criticism of the government policy was countered by the argument of a soldier’s sacrifice for the nation, thereby communicating to the public through the media that a true patriot is the person who willingly sacrifices his life for the government without asking questions. In the last nine years, many Indians, who still regard the mainstream media as the primary source of both news and knowledge, have internalised the narrative that questioning the government is an anti-national activity. And since the military does the government's bidding unquestionably, asking questions of the military is not just seditious but sacrilegious too.

This media-military nexus portrays Pakistan as India’s primary threat. Then through sly manipulation of this narrative, in which religion is diabolically introduced, Indian Muslims are presented as an internal security concern, which all nationalist citizens must watch out for. This is not only the politicisation of the Indian military, but the communalisation of one of India’s most apolitical and a-religious institutions.

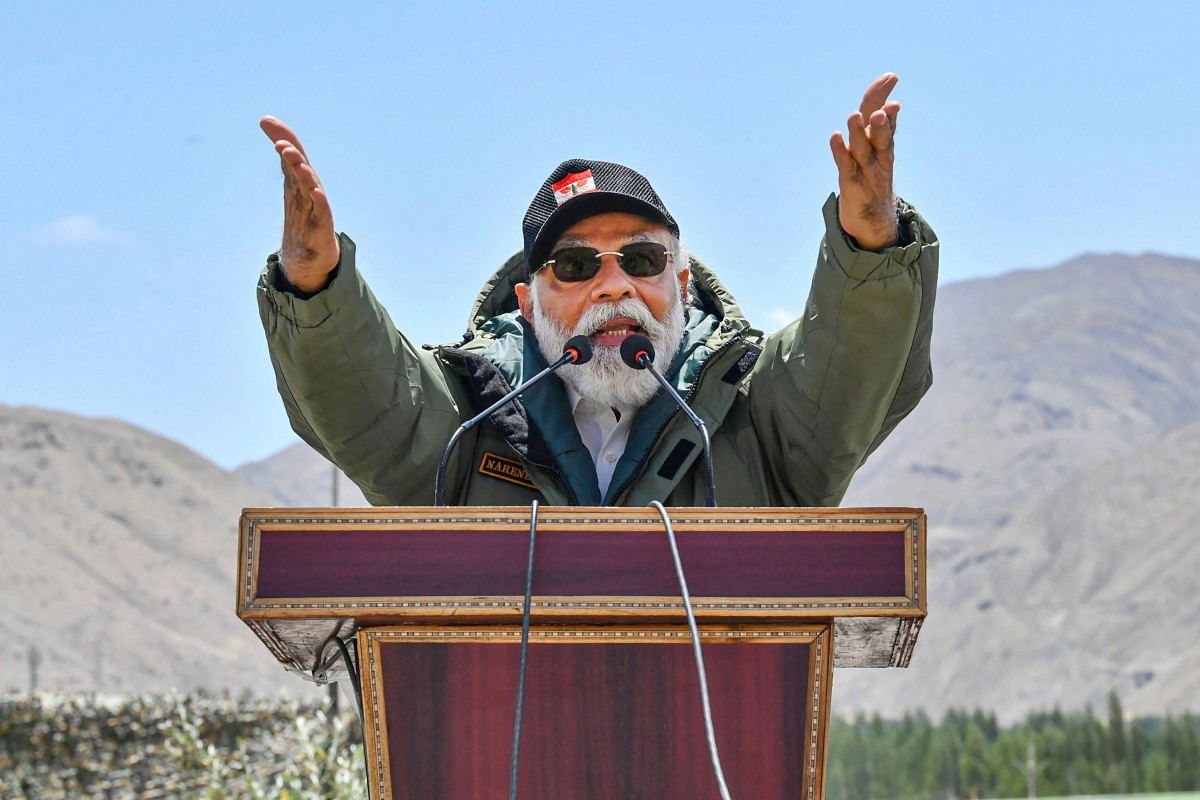

Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Ladakh. Photo: PTI

The challenges facing the Indian Army today are of its own mindset and vested interests, perpetrated by the growing tribe of retired officers with self-claimed expertise in counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism waxing eloquent on national television. Ironically, this expertise is also borrowed from the US, and its experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq, which Indian military analysts use as an example to contrast their successes in Kashmir. No wonder then, they remain removed from the realities of the Indian neighbourhood. Forget China, they remain oblivious of the degree of interoperability that Pakistan has achieved with its all-weather friend.

The Anantnag tragedy was waiting to happen, because the Indian Army started believing the government propaganda that the revocation of Article 370 on August 5, 2019 had resolved the Kashmir issue. It has started believing the crude sloganeering by retired army officers claiming that Pakistan is a walkover and that India can teach it a lesson any time it desires. It has started believing that China will not go to war with India because the Prime Minister says this is ‘not an era of war.’

Nothing can be hollower than a military which believes its own propaganda.

Pravin Sawhney’s recent book is The Last War: How AI Will Shape India’s Final Showdown With China.

This article went live on September twenty-sixth, two thousand twenty three, at zero minutes past twelve at noon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.