What I’ve Learned From Noam Chomsky

I once asked Noam Chomsky how he manages to remember so many facts and figures and hold audience attention. He replied that he didn't convey any new information, that his talks are based on materials already in the public domain, and that he simply joins the dots – providing context – and repeats the information consistently and in different ways.

His response was typical of his humility as well as his courtesy towards a much younger person to whom he owed nothing.

Chomsky teaches us that it is not necessary to be loud and sensationalist in order to be heard. This, together with the clear and courageous moral compass he has provided over decades, is a most valuable lesson.

Chomsky was already a legend when I first met him over two decades ago, in December 2001, when he visited Pakistan for the inaugural Eqbal Ahmad Memorial lecture series.

Dr Eqbal Ahmad had been an anti-Vietnam War activist in the USA in the 1960s. He later taught at Hampshire College and was among Chomsky's circle of friends, which included other intellectual giants and legendary figures like Howard Zinn and Edward Said.

He had returned to Pakistan after the death of Gen. Ziaul Haq in 1988 and was prominent in the peace and anti-nuclear weapons movements in the region. He passed away in May 1999, on the first anniversary of India's nuclear test, that Pakistan had followed.

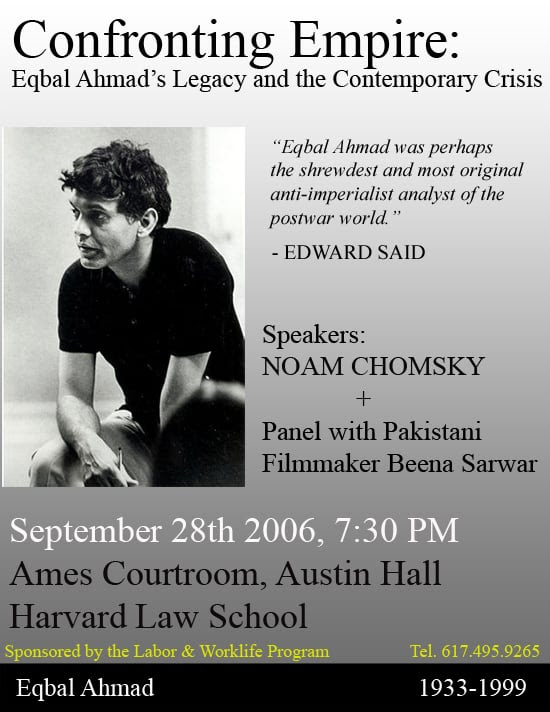

Poster of Eqbal Ahmad book launch at Harvard, 2006. Photo: Author provided

Confronting empire

In November 2001, Chomsky did a lecture series in India. Another fellow-traveller, the well-known physics professor and activist Dr Pervez Hoodbhoy, piggy-backed on that to invite Chomsky to Pakistan for the Eqbal Ahmad Memorial lecture series. These events were organised months earlier, and Pervez was initially worried about whether there would be an audience.

Then in 2001, the September 11 attacks in the USA took place. Chomsky cut through America’s outrage to point out that these attacks were historic not for their scale but because of where they took place, mainland America, which had not been attacked before.

Also, this was not the first, but "the second 9/11". The earlier, "far more serious" 9/11 was the one in 1973, the violent coup against the elected government of Salvador Allende in Chile.

Many in America were uncomfortable with his thoughts but in progressive circles here and around the world, his popularity soared.

I had just returned to Pakistan from London after doing an MA in TV Documentary and wanted to document Chomsky's visit to Pakistan for an international audience. Pervez agreed to let me record the series, and my Dutch friend Babette Niemel, then at VPRO Television in Holland, fought to get it approved for their 'Seven Days' video diary series.

Needing some B-roll, casual footage for the documentary, I had asked the organisers if I could follow Chomsky. They agreed to let me tag along to his room at the Avari Hotel in Lahore with cameraperson Mariam Pasha to escort him to the talk.

Noam Chomsky and his wife Carol had arrived in Pakistan to a celebrity welcome that discomfited them. Now, Chomsky politely conveyed that we were welcome to film his public events but that he and Carol were uncomfortable being followed by the camera.

We put our equipment away until he entered the venue where he was speaking. He walked through the packed hall to a standing ovation. A few days later, he addressed a larger audience at another packed venue, an indoor stadium in Islamabad.

In both places, people listened in pin drop silence as he spoke, lowkey and without histrionics, understatedly drawing linkages between history and politics. This has been the case whenever I’ve heard Chomsky speak.

There was a shameful exception, when he spoke at the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University where I was an international Fellow in 2005. In that intimate setting, another international fellow and her husband, both from Israel, kept interrupting Chomsky, despite being admonished by the moderator and other fellows.

Chomsky didn’t lose his cool, but I heard later that he vowed never to come back to Lippman House. I was glad to hear that the Nieman Fellows prevailed upon him to return in 2017 and that it went smoothly.

I was privileged to share the stage with him on a couple of occasions. In September 2006, John "Jack" Trumpbour, a Research Director at the Center for Labor and a Just Economy (CLJE) at Harvard Law School invited Chomsky as a featured speaker for the launch of a collection of essays, The Selected Writings of Eqbal Ahmad. It is to Jack's credit that he pulled off this event in a space that has tended to keep Chomsky out.

I was a speaker, along with Margaret Cerullo, Eqbal's colleague from Hampshire College and one of the book's editors. Stuart Schaar, Eqbal's “college buddy” from the 1950s at Princeton University – who we had interviewed for a documentary on Eqbal produced by Geo TV, Pakistan a couple of years earlier – was also a speaker. Like Chomsky, he has paid the price for his support of the Palestinian cause, sidelined in the mainstream academia as Eqbal himself was.

Another friend, journalist David Barsamian, who runs Alternative Radio and speaks Urdu and Hindi, flew in from Colorado for the event. A compulsive notetaker, I later wrote about the event, which remains so relevant today.

In his speech titled ‘Confronting Empire: Eqbal Ahmad’s Legacy and the Contemporary Crisis’, Chomsky talked about how Israeli attacks actually mean “Israeli and US attacks, since the USA supports Israel with weapons as well as diplomatic and ideological support”.

Israeli forces had earlier that year, on June 24, captured two Palestinian brothers, noted Chomsky, “a far more severe crime than kidnapping soldiers” as Hezbollah did on July 6, its first aggressive act in months.

We were then witness to an “unusual historic event” — the destruction of a nation” as Israel punished the Palestinians for “a terrible crime they committed: in the last free election they voted in the wrong people”.

Chomsky commented that the real reason for the Israeli (US-Israeli) aggression is that the then Hezbollah provided the only meaningful support for Palestinian rights, and also because they wanted to eliminate Lebanese deterrents that stand in the way of an attack on Iran.

The aggression has two consequences, he said. First, it deters negotiations. Second, it makes the dissidents and reformers more vulnerable, as regimes under attack tend to become harsher.

In April 2011 the American Friends Service Committee invited Chomsky to address a seminar at Boston University titled ‘Days of Hope and Challenge’, where I was the other speaker.

He also generously gave me time at his office at MIT, and I feel privileged to have been invited to contribute towards a compilation for his 90th birthday in December 2018. In my note, I shared some of my memories and thanked him for his vision, courage and consistency over the years, and his principled moral stands that have given strength and courage to so many of us over the years.

When Chomsky dropped in to the Southasia Peace Action Network seminar on the impact of 9/11 on Southasia and Southasians. Photo: Screengrab

Good trouble

Despite his legendary status, Noam – as he was to me and to many others – was always unfailingly humble and accessible. He always replied personally to my emails as long as he could, even if it was a one-line response to a question asking him to confirm whether a Twitter account in his name was genuine ("The twitter account from what I’ve heard is honest and accurate but I have nothing to do with it").

He was unfailingly generous in lending his name in support of the causes I and others reached out to him for, endorsing resolutions ranging from human rights and democracy to peace between India and Pakistan. In 2018, he joined many public intellectuals in urging Bangladesh to release photojournalist Shahidul Alam. He was also among the public intellectuals including Amartya Sen who endorsed a letter calling on Pakistan to release jailed publisher-editor of the Jang Group, Shakilur Rahman, in 2020.

My last interaction with him was in September 2021, almost 20 years after our first meeting.

I had invited him to address an online seminar hosted by the Southasia Peace Action Network or Sapan, that over 80 of us had launched in March that year to build a narrative for a Southasian Union along the lines of the European Union, or at the very least, regional dialogue and collaboration between all the countries of the Southasian* region.

Sapan holds public seminars on the last Sunday of every month. In September 2021, it was about 'The Impact of 9/11 on Southasia and Southasians'. The Taliban had recently taken over Afghanistan again.

By then Chomsky had moved to Arizona with Valeria, whom he had married after his wife Carol had passed away. He agreed to join but didn't show up, which was not like him.

The meeting ended. We stopped the recording and were chatting among ourselves, when Chomsky appeared. We asked him to speak and began recording again.

As always, Chomsky put the issue into perspective, arguing for the need to put people first. This would mean engaging with the governing authorities to mitigate and overcome human rights violations, while working with Afghans on the ground especially in rural areas rather than focusing on Kabul.

He advocated pressuring Afghans to shift the economy from opium cultivation to mineral resources, encouraging trade, development, and their integration into the region — “these moves can’t be made through sanctions”.

“Uppermost should be the fate of the Afghan people, he said, but engagement “does not mean overlooking the abuses”.

He wrote later apologising for the delay in joining ("computer-internet problems") and thanking me for the invite. "Clearly a very valuable event. Pleased to have been able to play a small part in it."

As news of his failing health circulates, my thoughts are with all those who have drawn strength and inspiration from him.

The best way we can pay tribute to Noam Chomsky is by following his example: Stand firm, keep calm, keep speaking out, put information in context, and keep doing our work.

*‘Southasia’ is written as one word, “seeking to restore some of the historical unity of our common living space, without wishing any violence on the existing nation states”.

Beena Sarwar is a journalist from Pakistan currently based in Boston. She is the founder and editor of Sapan News.

The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.