Hell Hath No Fury Like the Pakistan Army Scorned

What started off as a lovers’ tiff between the Pakistan army and its protégé Imran Khan in October 2021, over the appointment of an ISI chief, has culminated in the former virtually squishing the guts out of the ex-prime minister’s Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI) party. Over the past week, scores of PTI’s top leaders were forced to quit the party, and some even politics, while others stepped down from their party positions, after apologising in televised press conferences for the rioting that had ensued from Imran Khan's arrest on graft charges earlier this month. Khan was released upon the Supreme Court of Pakistan (SCP)'s orders a day after detention, but thousands of his cadres were rounded up by law enforcement agencies. The coalition Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) government is contemplating a ban on the PTI and has passed a resolution in the National Assembly to try the rioters in military courts. The clampdown, however, has the army written all over it.

The brass cracked its whip after the PTI workers had breached its General Headquarters (GHQ) perimeter, set the Corps Commander Lahore’s residence and the historic Radio Pakistan Peshawar on fire, and rampaged military symbols and installations around the country, following Imran Khan’s detention. After his ouster in a no-confidence move last spring, the former PM had gradually been ratcheting up his rhetoric against the former Chief of Army Staff (COAS) General Qamar Javed Bajwa and repeatedly blamed him for orchestrating his dismissal. He then pointed the finger at a serving chief of the ISI’s powerful Directorate C Major General Faisal Naseer, alleging that he had ordered a hit against him. Imran Khan targeted the incumbent COAS General Asim Munir first through innuendo, and finally by directly holding him responsible for his arrest. The junta, however, had shown restraint over the past 13 months and responded tepidly to Imran Khan’s allegations.

But in the events of May 9, the SCP springing Imran Khan from detention, and his defiance the day after, the brass saw the ingredients of a coup, albeit a failed one. There was not going to be a second chance. The gloves finally came off. Imran Khan, for his part, probably forgot the old dictum that when you strike at a king, you must kill him. He made a monumental miscalculation – and missed. Even if one discounts the rumours that there was a formal plot to dislodge the army chief, Imran Khan’s calculus was clear: with pockets of support within the army, judiciary, and general public, he could bring down the top brass and upstage the PDM government.

May 9, in Imran Khan’s mind, provided an ideal alignment of the three. His arrest was supposed to trigger mass protests compelling the generals ostensibly allied with him to force General Munir into stepping down, while the SCP led by the Chief Justice of Pakistan (CJP) Umar Atta Bandial would deliver a knockout blow to the PDM government by holding PM Shehbaz Sharif in contempt over the delayed provincial snap polls. Imran Khan clearly overestimated his support within the army and the masses. There was neither a colonels’, or in this case corps commanders’, coup nor an eruption of mass protests. On the contrary, burning down and vandalising military installations perhaps forced Imran Khan’s sympathisers in the army to hold their silence as General Munir finally asserted himself. And other than granting Imran Khan bail, the CJP, who heads a bitterly divided court, wasn’t able to come to the party’s rescue either.

Founder and Leader of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, Imran Khan. Photo: Screengrab via YouTube/PTI

The PTI leaders who were released by the courts were immediately rearrested, some of them, almost half a dozen times. They were only released after publicly denouncing the events of May 9, blaming Imran Khan for the vandalism, resigning from the party or even politics, and glorifying the army. All of them seemed to be reading from the same script. While the breakneck speed of the mass exodus was a bit surprising, the way PTI has unravelled shows that the army is not just actively dismantling its one-time favourite project, but also wants Imran Khan completely isolated.

Billboards and posters bearing images of Imran Khan and his inner coterie – labelling them traitors – have been mysteriously splashed around the country. Television channels and even movie theatres are running video ads with footage of the May 9 violence and labelling the rioters and instigators as enemies of the state. Banned sectarian and religious outfits, as well as the mainstream political parties like the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PMLN), the Pakistan Peoples Party, and the Pashtun nationalist Awami National Party have gone on overdrive with messages and rallies in support of the army.

The government has already handed over 33 protestors to the army for a military trial. The Pakistan army, scorned by its former darling, seems to be laying the groundwork for trying him in a military court as well. While the civilian government is owning the decisions, it clearly is not making them. Pakistan or at least the Punjab province is under virtual martial law. But because of the way Khan tormented his foes and even friends at the height of his power, there is hardly anyone shedding a tear for him.

A parallel from the past

Imran Khan is a textbook demagogue in that: “motivated by self-interest, he evinces little concern for truth and is an opportunist.” He “appeals to greed, fear, and hatred by stirring up the feelings of his audience and leading them to action despite the considerations which weigh against it.” Imran Khan’s party has been more of a cult around his personality than a political movement. His own creed and methodology have been of a classic populist who claims that a small corrupt elite – represented by the PMLN and PPP in Pakistan’s case – is exploiting the moral majority. And like populists of all shades, he too alleged that the corrupt local elite is being supported by enemies from without and their agents from within. The populist mind and strategy seek complete domination over the political opponents, which by itself is a total antithesis of democracy.

In this, Imran Khan comes close to the PPP founder and late PM, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Incidentally, when the army toppled Bhutto in 1977, the political opponents and associates that he had hounded and the parties that he had banned, breathed a sigh of relief. Many of them made common cause with the military regime of General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq. It was not until two years after Bhutto was hanged by the army after a sham trial that other political parties had a rapprochement with his PPP and launched the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy in 1981.

For all his faults and origins as the army’s protégé, Bhutto, however, was a political giant who did not need the army’s shoulders to stand tall. He had a genuine support base across Pakistan and devoted party leaders and cadres who kept the PPP going despite the junta’s brutal crackdown. Imran Khan, on the other hand, has been completely beholden to the army for his political existence. I had noted in this space last year that the Imran Khan project:

“came to fruition on General Bajwa’s watch in 2018 but installing Khan as its puppet prime minister had been the army’s longstanding project, fostered by several army and ISI chiefs. The junta deployed tremendous resources to organize his Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI or the Justice Movement) and herded the army establishment-allied politicians to join him. It harnessed the media to both project Khan as the nation’s saviour and his opponents as vile and corrupt. The army even co-opted the judiciary to knock out Nawaz, to pave the way for Khan’s installation. Now that the brass wants Khan to fall on the sword for their sake, he has very little wherewithal on his own to resist them with. The components of the scaffolding that upheld the façade of this Potemkin Democracy, are being withdrawn one by one. While the lack of media and judiciary’s support would be a problem for the prime minister eventually, the most immediate concern is the flight of his partymen and allies.”

The Pakistan Army’s playbook is that predictable! But that also informs us that we have not seen the last of the army’s vengeance in this round. While his party has been dismantled and the rump degraded enough to run an effective election campaign, Imran Khan still retains a significant appeal among a large section of the population. But more than that, he is unrepentant, which the army would perceive as an existential threat to the new political order it is engineering. Like with Bhutto, there is a talk about what exactly to do with Imran Khan. Everything from banning his party and letting Imran Khan go into exile, to letting him off the hook and allowing him to participate in the next elections, to putting him on trial and condemning him for life, are being contemplated. In the summer of 1977, when Bhutto was released on bail by a high court, drawing large crowds, he immediately trained his guns on the army generals and assailed martial law. That perhaps was the moment the generals made up their minds about his final disposition. Bhutto was rearrested and the rest is a tragic history. If the past is prologue, Imran Khan’s well-known vindictive nature and his indictment of the army chief, right after being released on bail have sealed his fate too. While it might be near-impossible to do the unthinkable today, Imran Khan is in serious trouble. It is difficult to see how he can extricate himself from the straitjacket, largely of his own making.

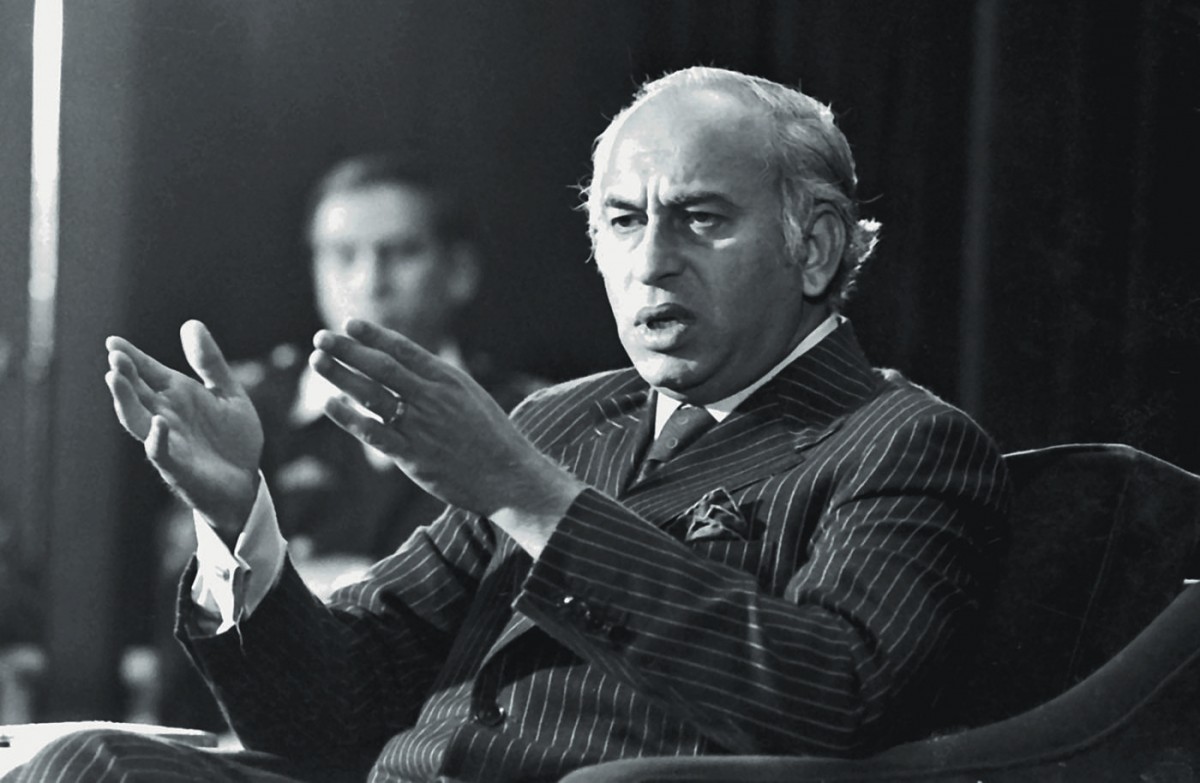

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Bhutto’s words delivered after that fateful release, are worth recalling though. He had said:

“I am not worried about the impact, the imposition of martial law will have on politics. But I am worried about the future of Pakistan.”

What lies ahead for Pakistan today is equally concerning. The army can’t and doesn’t actually need to declare martial law, as its PDM quislings are only too happy to play second fiddle in the Hybrid Regime 2.0 that is underway now.

The hybrid regime experiment with Imran Khan as its frontman was conceived by the army to capture back the little political space it had ceded to the civilians since the 2008 ouster of the last army dictator, General Pervez Musharraf. By dismantling its Imran Khan project, the army was supposed to revert to a more restrained tutelary role. But what has transpired is the complete opposite of that. Just over a year ago, the army had claimed to have become neutral in civilian matters, but instead, it has plunged even deeper and more sordidly into politics. That neutrality, it was claimed, had come after a long and hard introspection by the brass. But the facts on display today betray that tall claim. Imran Khan rode roughshod over Pakistan’s polity not because he was all-powerful in his own right but because the army fully enabled and backed him in every excess he committed. The brass decided to change horses only when the project became untenable due to a tanking economy. No one really bought the neutrality and introspection claims or thought that the army would hold its then brass accountable. But by trotting out General Bajwa on what the army called the ‘respect for martyrs’ day’, the brass has laid bare its impunity. The ex-COAS sitting next to General Munir is effectively the army thumbing its nose at not just Imran Khan but also the PDM leadership, many of whom were on the receiving end of the previous hybrid regime – of which General Bajwa was the godfather.

The PDM’s honeymoon with the army will not be eternal either. With its multisystem failure and near-default economy, the only way forward for Pakistan is to hold general elections and restore a modicum of legitimacy to the government. The current National Assembly completes its term in August. So far, the thrust of the PDM-COAS combine had been to delay the elections to keep Imran Khan from scoring big. The spectre of a resurgent Imran Khan had kept the PDM parties together and also allied with the incumbent COAS and army. Once the common enemy has been disposed of, the PDM parties are likely to pursue their individual agenda and vie for the army’s singular patronage, as the latter has buttressed its position as the ultimate arbiter of politics.

But the very nature of power structure – even in a crippled and nominally constitutional democracy like Pakistan – is such that hybrid regimes are untenable and even the weakest of prime ministers eventually rub the junta the wrong way, often at their own peril. And future dispensation(s) won’t be any different. Unfortunately, by joining the army propaganda chorus and passing parliamentary resolutions supporting the trial of civilians under the Army Act, 1952, which is repugnant to the due process of law, the PDM has normalised the military courts for short-term political gains. Banning the PTI and condemning Imran Khan to whatever fate would also serve as future templates for the army’s coercive power to control both the political class and process. Imran Khan is an individual and unlike Bhutto, would leave a minor mark on the country’s political history. But the virulent mutations being introduced into Pakistan’s body politic by a furious army to dismantle its own project would continue to reverberate for long.

Mohammad Taqi is a Pakistani-American columnist. He tweets @mazdaki.

This article went live on May thirtieth, two thousand twenty three, at thirty minutes past four in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.