Bengaluru: Not just the moon’s south pole, but areas at high latitudes that have large slopes towards the poles too may harbour conditions suitable for the occurrence of water-ice — ice formed from fresh or saltwater, as opposed to snow. A team including scientists from the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) made this recent, serendipitous discovery when they were studying the top layer of the moon with an instrument aboard the Chandrayaan-3.

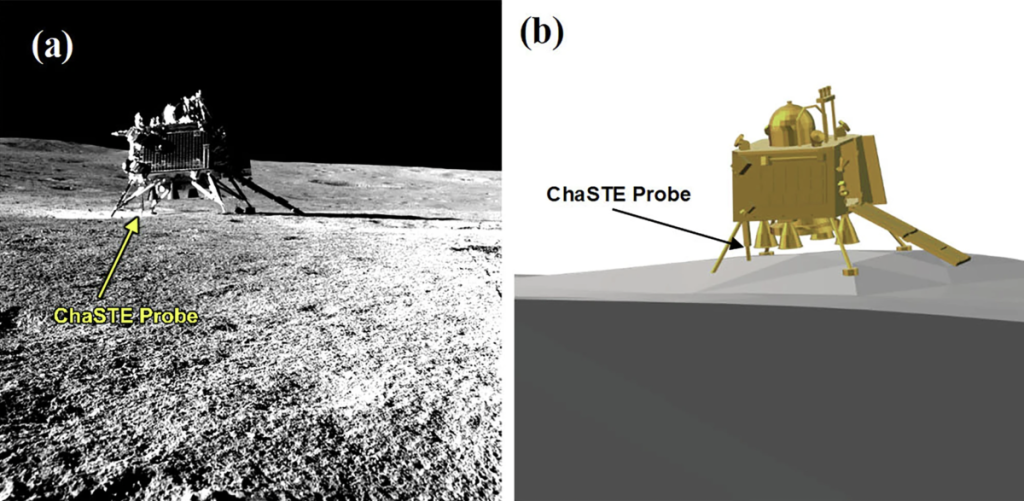

For billions of years since its birth, meteorites, space rocks and charged particles from the cosmos have bombarded the moon. Together, they form the lunar soil — which is different from the Earth’s organic soil. The first layer is grainy, composed of rocks, boulders and fine dust. It can be a few metres to about 20 metres thick. Indian scientists — including from ISRO’s Ahmedabad, Visakhapatnam and Thiruvananthapuram teams — were interested in measuring how heat conducts through the layer and how its temperature varies at the Chandrayaan-3 landing site, about 70°S of its equator — close to the lunar south pole. The Vikram lander carried instruments, one of which was Chandra’s Surface Thermophysical Experiment (ChaSTE). Its temperature sensors dug into the top 10 cm of the lunar soil and measured how the temperature varied across depth. Their observations have been reported in the journal Nature Communications Earth & Environment on March 6. “CHaSTE has given the first-ever in situ measurement of a high latitude region,” said Karanam Durga Prasad, faculty in the Planetary Sciences Division at the Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad, one of the study’s co-authors.

Water-ice and questions

The authors claimed, through a detailed study of the lunar conditions, that the regions away from the poles can harbour water-ice at a shallow level of the top layer. Water-ice is an important resource on the Moon. It could hold the key to future explorations that require human presence, a source of drinking water, a cooling agent for missions, or for breaking it down to hydrogen for fuel and oxygen for survival of humans. But scientifically, lunar water-ice could be key to understanding the history of the solar system, and potentially, the source of water on Earth. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) future Artemis missions will particularly target the lunar south pole, home to regions permanently shadowed from the Sun, which scientists believe are conducive to trap water.

Also read: Chandrayaan-3 Finds Evidence of Global Lunar Surface Magma Ocean

The trouble with missions that target landing and operating there, however, is that its terrain is rugged (including craters, boulders and uneven surfaces) it witnesses extreme fluctuations in temperature across day and night, and has permanently shadowed craters — potentially some of the coldest regions in the solar system — which can affect electronic systems. But with Chandrayaan-3’s landing site being close to the lunar south pole, Indian scientists have been keen to know if water-ice could exist near the landing site. And if it does, in what quantity it could occur here.

According to previous observations by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter’s Diviner instrument, operated by NASA, the temperatures at the CHaSTE site are supposed to vary between 280 to 320 kelvin, or 7 to 47 ℃. The Indian researchers used a combination of observations from Chandrayaan-2’s Orbiter High Resolution Camera (OHRC), direct measurement by CHaSTE, and mathematical modelling — to conclude that the peak temperature was going up to 355 kelvin or 82℃. They were surprised to find the large difference from expectations. To investigate why, they carried out temperature measurements with sensors at the centre of the Vikram lander, close to a metre away. Their analysis revealed that the CHaSTE probe was standing on a slight depression — of about 6° — towards the Sun. The conclusion indicates that the local difference of slopes can significantly alter the temperatures on the Moon’s surface.

‘Not surprising’

Both Tamilarasan Kuppusamy, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and Paul Hayne, a faculty member in the Astrophysical & Planetary Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder, USA, not involved in the study, said the results aren’t surprising.

“Given that the probe measured temperatures on a Sun-facing slope, the higher temperatures compared to Diviner measurements are not unexpected,” Hayne said.

However, Kuppusamy did not rule out that the difference could be due to errors in calibrating the instrument, or that the lunar soil itself can vary across the distance between the centre of the lander and the CHaSTE probe.

(a) Vikram lander along with CHaSTE probe taken by Pragyan rover and (b) authors’ mathematical model of the region. Photo: ISRO.

Using the mathematical model, the ISRO researchers predicted the temperature at the same location at night: it can go all the way down to about 110 kelvin, or -163 ℃ – ideal for the formation of water-ice on the surface. “The results show the importance of ground truth measurements, especially for surface temperatures, which can vary widely compared to what we measure from orbit,” said Hayne.

What does this mean?

If the same model is correct, the Indian scientists’ conclusion is that regions which have more than a 14° slope away from the Sun — towards the pole — are ideal to harbour water-ice. That is because the temperatures, even during the day, can be sufficiently low to aid the formation of water, which can seep down the topmost soil layer and stay put. “Certain locations at high latitudes can have environments similar to poles so they have the ability to prospectively harbour water-ice,” said Durga Prasad, adding that this is the first time anyone has claimed so.

While agreeing to the conclusions, Hayne warned: “It’s important to note that the surrounding terrain can strongly influence temperatures in shadows on the Moon. Reflected sunlight from crater walls for example can raise temperatures in shadows, which may limit ice stability.”

Kuppusamy thinks the results are interesting enough to warrant deeper investigations. “I hope future missions will include similar heat probes to measure the Moon’s temperature on the ground,” agreed Hayne. If they do find differences due to the local slope of the land, scientists could think of human missions at such latitudes instead of at the Moon’s south pole.

Meanwhile, Durga Prasad claimed that since the CHaSTE observations were only at one location, the team could not infer the amount of water-ice. However, they have more observations from nearby regions from Chandrayaan-2’s high resolution camera. “Using that, we wanted to… understand how water is going to accumulate and how it could be stable,” he said. “Maybe we can come up with the water-ice prospective map of these locations with this dataset.”

Debdutta Paul is a freelance science journalist.