Adding Colour to The Whites

Test cricket has undergone a massive shift in recent years in how a result-oriented pitch is almost deemed a non-negotiable. It may not instantly sound like a radical change but it’s among the most significant ones. Pitches have hardly been as unkind to batters for a sustained period all around the world as they have been of late.

The introduction of World Test Championship has incentivised teams into preparing surfaces that give them the best possible shot at taking 20 wickets even if it compromises the number of runs they manage to score. Pronounced seam, extra bounce, sharp turn have all been on offer for extended periods raising the difficulty levels for batsmen considerably.

Fast bowlers with metronomic accuracy being able to land the ball in that nagging length over after over are becoming the game’s most prized asset. The core principles of Test batting that emphasise on leaving the ball till the time it stops seaming are becoming somewhat outdated because it doesn’t quite stop seaming at all. Even those with militant discipline outside their off-stump are struggling to survive because the very physics of the contest has now been gamified to their disadvantage.

Test cricket is at a point in its history where it couldn’t have been more opportune to be a Scott Boland. But it’s also at a point where it couldn’t have been more inopportune to be a Virat Kohli.

And nothing could’ve illustrated this more painfully than the dejection on Kohli’s face as he once again nicked at one off Boland, guiding it straight to the second slip at Sydney earlier this year. The shot marked the end of an exasperating tour for Kohli. Many feared it was the last we’d seen him don the Indian whites on the Australian soil. Well, turned out – but only four months later – that it was the last we saw of Kohli at all at the Test level.

In hindsight, Kohli probably shouldn’t have played that Test in Sydney. His captain and longtime comrade Rohit Sharma, undergoing an even more torrid time down under, had ‘stepped out’ of the Test in the hope of finding some breathing room. The team management could have nudged Kohli too into taking a similar call which may or may not have served the team better but would certainly have saved him from the relentless trial by Boland.

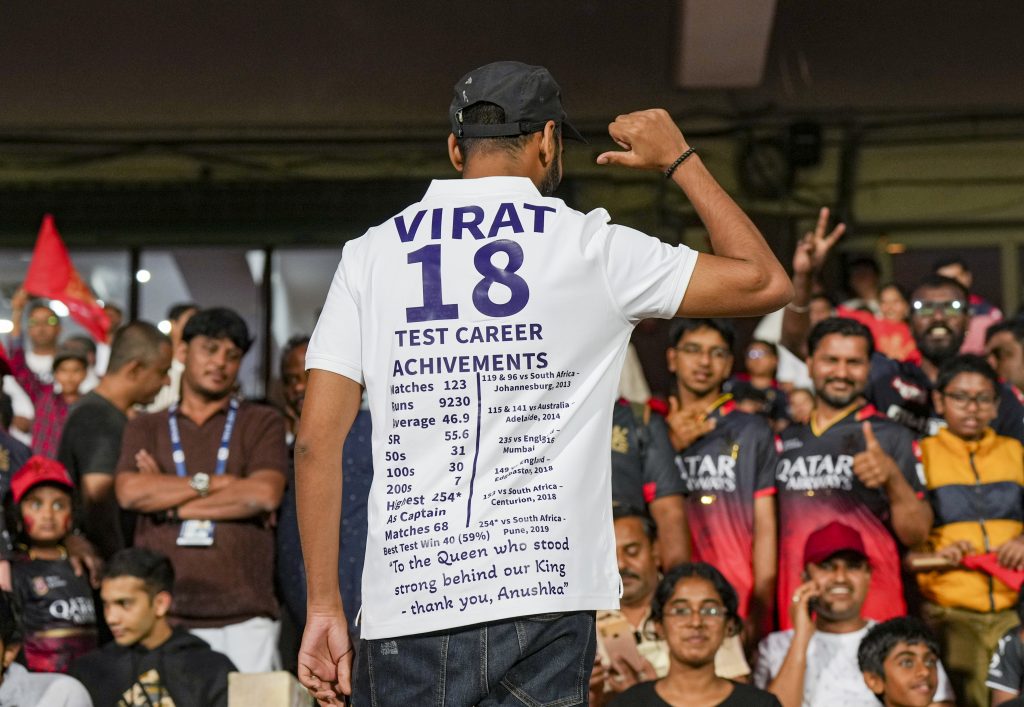

A Virat Kohli fan wears a number 18 white jersey, showing his stats and achievements, in his honour after he recently announced retirement from the test cricket at the M Chinnaswamy Stadium, in Bengaluru, Karnataka, Saturday, May 17, 2025. Photo: PTI

Whether or not Kohli was told he’s no longer in the team’s plans for the England tour will remain a matter of speculation for a while but few could argue his time wasn’t up as an elite Test batter. Mediocre returns for 4 out of last 5 years were going to get increasingly harder to explain away no matter what filters one applied.

There’s even media conjecture over him wanting captaincy back following Rohit’s retirement and that it was steadfastly refused by the management. That may well have led him to wind things up rather hastily without staging an exit that’d feel befitting to the career he’s had.

Kohli’s regression, while undeniable, was particularly discernible because few have had a prime that rivals his. Unlike many in India, Kohli wasn’t necessarily a protégé whose greatness at the highest level was imminent. He had to earn greatness the hard way.

Barely a couple of years into international cricket, he was already among the more prominent limited-overs batsmen in the world. And yet, there wasn’t really a persistent clamouring for his selection in Tests in the media circles. But from that extended run he’d had playing One-day internationals for India, Kohli had learned the craft of run-production in a way that Test cricket would only feel like a rather smooth progression than a destabilising leap.

Most players that make it that far have had their batting fundamentals sorted. The technique is largely sound. Experience at lower levels has had their temperament adequately built up. There’s little actually to tell players apart at the highest level, hard it may sound to fathom. The one differentiator that perhaps elevates the most successful ones from the rest of the flock is they learn to think of run-scoring as a skill separate from batting.

Cover drives and front-foot pulls make for great highlight packages. But it’s the ugly work that goes in between that contributes to the volume of runs. Inventing scoring opportunities off good balls by getting into better positions, rotation of hips, flicking of wrists, and an ability to meet the ball at better angles is how the time spent in the middle is maximised at lower risks.

oyal Challengers Bengaluru's Virat Kohli plays a shot during the Indian Premier League (IPL) 2025 at M Chinnaswamy stadium in Bengaluru, Thursday, April 24, 2025. Photo: PTI.

If Kohli’s career trajectory is to be revisited, it becomes increasingly obvious that he learned each of these much sooner than an average player would. He may never have possessed the flashiest of shots but in his mastery of innings construction, you could see what greatness truly looks like.

If Kohli spent time in the middle, runs were inevitable. There was very little scope for an in-between. There were very few ways to bog him down. And he did it for the most part with a fairly limited arsenal of strokes – a glorious drive if you pitch it up, a sublime swivel-pull off anything short, and an impeccable flick if you end up too straight. It shouldn’t seem too difficult to tie down a batsman of this profile.

But in his prime, Kohli was among the finest manufacturer of runs the game has seen. He had these extremely effective ways of dabbing the ball just that wide off the in-field to be able to get off strike. His wristwork allowed him to place the ball at a precise point in the field where he could run two. It was probably the instinct he’d picked from being the ODI batting behemoth that he was.

Run-production in Test cricket is among the most straightforward of metrics to measure success. Unlike in the shorter formats where other qualifiers like speed of scoring, impact quotient, maximisation of certain phases are equally critical, things remain quite simple in Tests – a large quantum of runs at great consistency puts teams in winning positions more often than not.

The onus of scoring a large chunk of these runs usually befalls upon those batting in the positions most conducive to scoring big. Therefore, Kohli’s ascent to No. 4 in the Indian lineup immediately post Sachin Tendulkar’s retirement meant he’d been afforded the status of the main man. And it took him very little time to vindicate this faith the team had vested in him.

Between 2014 and 2019, Kohli had no parallels in the Test arena barring his foremost nemesis and quite possibly the greatest post-war batsman Steven Smith. Outside the Australian, Kohli stood far and above everyone else and his batting had hit the proverbial stratospheric scales. The period saw him exhibit a home dominance that beggared belief. He kept amassing runs at a ridiculous rate; so much so that double hundreds kept coming like no one’s business. He was both invincible and inevitable.

Virat Kohli warms up before an Indian Premier League (IPL) 2025 T20 cricket match at the M Chinnaswamy Stadium, in Bengaluru, Karnataka, Thursday, April 10, 2025. Photo: PTI.

The period also saw him drop three all-timers in 2018 on three of the toughest away assignments at Centurion, Birmingham, and Perth. In a year in which fast bowling was statistically impossible to deal with, Kohli carved out a whole new pedestal to occupy.

Many greats have had similar peaks at different points in time but Kohli’s still feels more exceptional in that he could create a theatre around his runs. His runs had a profound effect on the oppositions beyond merely beating them. His runs hurt them. Kohli was consciously aware of this and wouldn’t miss a single opportunity of sending reminders.

It's therefore slightly discomforting that it only took a year from those astonishing heights of 2018 for the aura to drop completely. It was the New Zealand tour early in 2020. Kohli looked at odds against the seaming ball. But he’d never been the most adept at dealing with excessive movement. Surely it couldn’t have been an indication of a terminal slump?

But every successive series since, his troubles seemed to compound. Spin at home became a constant deterrent. Seamers around the world discovered a new weapon called the ‘wobble ball’. Keep feeding Kohli into the channel outside off and his commitment to front-foot prod would ensure he’d nick at one.

The lack of back-foot game on the off-side put a limit on his scoring options on pitches that assisted seamers longer than usual. Driving on the up was no longer a choice thus but came from a place of necessity. It was not like Kohli couldn’t buy a run. But there was barely any fluency to batting now.

Every run came that much harder and there was plenty of grafting involved now. The trademark cover drive too wasn’t executed with the natural bat-swing anymore but had grown visibly checked in its execution. But most importantly, even after spending time in the middle, teams could sense he wasn’t too far from committing a fatal error.

For too long, most believed he’d eventually find a way. But averaging barely a few decimal points above 30 over a five-year period meant even his status as a legacy player was no longer going to be an insurance against his axing.

Whether it indeed was an axing too will remain a matter of speculation. But it’s hard to believe it completely came from a place of inner conscience; especially considering he even turned up for a domestic First Class fixture for Delhi not too long ago. At least until then, it’s safe to say, he did harbour hopes to continue in the Whites for a little longer.

Virat Kohli plays soccer during a practice session ahead of the ICC Champions Trophy 2025 final cricket match between India and New Zealand, in Dubai, UAE, Saturday, March 8, 2025. Photo: PTI.

It’s impossible to definitively tell whether Kohli still had any gas left in his tank. Perhaps the dip in his returns had reached a point where it’d become untenable to continue pretending everything was normal. It sure did look at one point that he was mounting a serious challenge to Tendulkar’s legacy.

But in the end, he fell reasonably short. And perhaps, rightly so. Tendulkar’s game was always much more rounded – his range much wider, his defence much tighter, and his eye much sharper. But having been left appreciably behind even among contemporaries like Smith, Joe Root, and Kane Williamson may be slightly harder to come to terms with for Kohli.

But there’s no bigger affliction about Kohli’s Test career than the fact his towering superstardom managed to completely subsume the batsman he was. The entire Indian (and much of foreign) Cricket media ecosystem preferred selling Kohli’s larger-than-life personality cult to his truly enigmatic batting.

A deluge of articles, podcasts, social media posts, and interviews since the time he announced retirement has flooded the social media. And the overwhelming proportion of that space has been allotted to talking about him in the emptiest possible adjectives. The man who saved Test cricket, the one who never backed down from a fight, the one who represented a ‘new India’ – it’s as if the pre-eminence of his Test batting is not even an afterthought.

Cricket media has always had a puerile fascination with the idea of captaincy – grown men of objectively mediocre intelligence continue to peddle this idea that teams’ fortunes hang on a saviour character, a leader of men, a trailblazer without whom they wouldn’t have learned the art of winning Test matches.

This extremely asinine and self-indulgent exercise has only grown in the age of social media and it manifests in its worst possible form in how the media covers Kohli. The worst of orientalist clichés are casually thrown by the English and Australian journalists and commentators when they promulgate without a hint of hesitation that Test cricket in India wouldn’t have survived if not for Kohli emphasising on its important so much.

Never mind not bothering to cite any authentic reference indicating dwindling levels of interest in Tests among Indians right before Kohli took over captaincy, there are some very casually racist implications here – that Indians on their own would not have bothered watching anything other than the IPL and that it took one man repeatedly insisting they learned to love a better product.

Illustrious legacy 🇮🇳

Inspiring intensity 👏

Incredible icon ❤️The Former #TeamIndia Captain gave it all to Test Cricket 🙌

Thank you for the memories in whites, Virat Kohli 🫡#ViratKohli | @imVkohli pic.twitter.com/febCkcFhoC

— BCCI (@BCCI) May 12, 2025

The fawning and drooling over his on-field shenanigans is equally embarrassing. Kohli took over captaincy at a time when pitches around the world became much more rewarding for fast bowlers than before and he chanced upon a generational cricketer called Jasprit Bumrah.

It’s not his tendency to deliver mouthfuls and get the crowd going that led to his bowlers taking wickets. Quite the opposite in fact – it was the intensity of bowlers that let his theatrics look enthralling. But from sycophancy-laden broadcasting partners to serious media houses like ESPNCricinfo, nobody ever got tired of repeating something so inordinately fatuous and inane.

It's usually those who’ve done very little of substance who require for a bloated version of their personality to be sold in the media. It’s to make up for the inadequacies in what they were actually meant to do – in cricketing terms, runs and wickets.

And that is exactly why the entire charade feels doubly frustrating when done to a legit all-time great Test cricketer like Virat Kohli. There are no holes here that anybody needs to cover for. But an entire coterie of middling and amateurish media professionals have ensured Kohli the cricketer takes a firm backseat in service of the daemonic figure that they’ve contrived in their prosaic imaginations.

Kohli’s story in the whites is surely going to feel incomplete. Despite steadily depleting returns, he at no time looked a completely spent force hopelessly out of touch with his craft. Or perhaps it was inertia on part of those too used to having him around that refused to entertain the thought that it was over.

Well, over it anyway is now. And it’s going to take time before it feels normal again. It’ll be a while before the eyes adjust to a new batting roster, a new slip cordon, a few new voices exchanging trifling chatter over the stump mic. And during that transition time, the whites are certainly going to feel a little faded, a little less colourful.

This article went live on May nineteenth, two thousand twenty five, at zero minutes past nine at night.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.