Ted Dexter: Cricket's 'Renaissance Man' Whose Legacy Extends Beyond the Pitch

The England and Sussex cricketer, Ted Dexter, who died last week at the age of 86, is remembered for his dashing stroke-play and as one of the best players of fast bowling. The innings recalled most often is the one where he took on the mighty West Indian seamers Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith, to score 70 of 75 balls in a thrilling draw at the Lord’s in 1963.

Batting geniuses are often stored in memory via a stellar innings that carries their fame across the decades and is retold in their biographies and obituaries. The recollection of the courage, grace and grit of a particular innings is a much richer narrative than the recounting of statistics, which provide an inadequate index of a player’s virtuosity.

This small bit of footage that is available from the 1963 match shows a cut and a pull by Dexter off Griffith. The cut is severe. The blade flashes, Dexter is perfectly balanced and follows the ball with his eyes as he rises with it. His bat face opens and directs the ball through point with precision, while immense power is imparted by his forearms. The key to the stroke, though, is a brief moment when you can see that he has read the length early and selected his shot. Experts speak of how the greats always have that extra bit of time, playing strokes. Dexter clearly belongs to that category. While the subsequent pull is not off the middle and the batter seems to be hurried into the shot, one can still see how the ability to pick the length early allows him to be in a good position and play the ball under the eyes.

Writer and broadcaster E.W. Swanton counted Dexter as one of the four batsmen of his time who played every stroke in the book, the other three being Gary Sobers, Rohan Kanhai and Graeme Pollock. Even the evidence of 43 seconds of footage is enough to see why this was true.

Dexter does not need to hide his figures behind just this one innings of brilliance. His aggressive middle order batting came at an average of 47.89 and went up to 53.65 away from home. Not figures to be scoffed at. He was a handy bowler too, taking 66 wickets in 62 Tests at 35 runs apiece, excellent for a part-time medium pacer.

He scored heavily everywhere and only in Australia did he average under 40 runs an innings. However, his numbers there are lowered by poor returns in the four innings he played there on his first tour in 1959 as a rookie. On his second tour to the country in 1962/63, when he also captained, he made over 50 in five out of ten innings and averaged 48 in a hard-fought series that ended 1-1. His highest was a 99 that helped secure a crucial draw in the opening test.

After Dexter had set up the second match for the English victory with a 93, the Belfast Telegraph wrote that England’s’ “[M]ain hero was the England captain, Ted Dexter, who laid the (Richie) Benaud menace well and truly with two big innings”.

Dexter also captained the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) team that toured India, Pakistan and Ceylon (as Sri Lanka then was) in 1961-62. India, led by Nari Contractor, won their series 2-0 and it was the country’s first series win over England. However, Dexter did very well, scoring 409 runs in five tests at 58.42 an innings. Against Pakistan, England won the series with the skipper averaging 101, making a double century and a fifty in the three tests played.

For me, born a few decades too late to watch him live, the figures, the anecdotes and the writings on Dexter vividly bring out his versatility. He appears to have tried his hand at everything; cricket, golf (he practiced his swing while fielding), politics (he stood for Parliament from Cardiff South-East as a Conservative candidate and was routed by Labour’s James Callaghan, later to be Prime Minister), journalism and cricket administration. Indeed, former cricketer and broadcaster Mark Nicholas’ obituary refers to the ‘renaissance man’ in Dexter and his wish to engage with different disciplines, which were met largely with success.

His versatility was complimented by grit and application, as Dexter prided himself on the ability to master whatever task or challenge came his way. On the occasion of Dexter being named one of the Wisden cricketers of the year in 1961, Robin Marlar, his Sussex teammate, wrote about how Dexter had considerably improved his fielding skills: “Once laughed at as a fielder, and prone, so (Jim) Laker tells us, to practising golf shots in the outfield, Dexter has become a fine cover-point and last season revealed surprising talent as a short square-leg, where his reactions were phenomenal”.

It was the intellectual disposition of the man that supported such application. Describing himself, with some immodesty, as the ‘renaissance man’ on his blog, where Nicholas also picked up the term from, Dexter says that to be such a man, “you do not need to excel at any one activity. It is enough to tackle it seriously and see how far you get.”

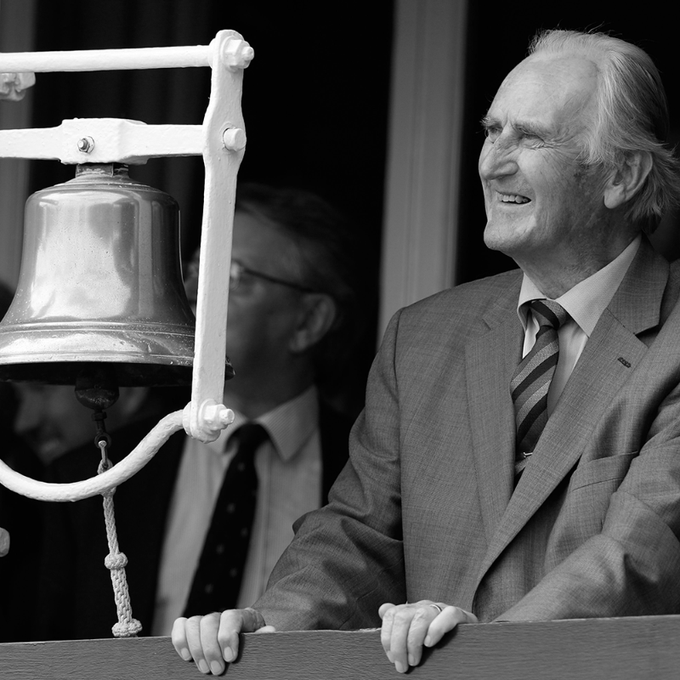

Ted Dexter. Source: Lords.org

The statement foregrounds an attitude that prides itself on the mastery of a principle, obstacle, or situation. The attitude was exhibited in his captaincy as well. David Hopps suggests in his sketch of the cricketer that Dexter, as captain, tested out strategies on the field often out of boredom; there was always the quest of a new principle or idea that would further the relevance of the game (and life) to him. There were many positives to this approach, not least observed in the cricketer’s stellar batting record when in charge. Leading from the front, he averaged nearly 54 in 30 tests as skipper. As Sussex captain, his quest for innovation led to multiple Gillette Cup titles, the domestic one-day tournament in England back in the day.

One of England’s greatest captains, Mike Brearley states in The Art of Captaincy that Dexter “was an excellent theorist on the game; but when his theories failed to work, or he had no particular bright ideas, he would drift; and the whole team drifted with him. I would guess that Dexter was, in those days, more interested in ideas than in people”. Brearley’s analysis acknowledges the intellectual force driving the man as well as its failing.

There is perhaps no better example of this than the 1964 Ashes where Dexter, curiously, refused to have a fielder “on the hook” for pacer Fred Trueman when the latter was bowling to the Australian batter Peter Burge at Headingley, despite the bowler’s insistence. Burge hooked and pulled his way to 160. Australia eventually won the series. Dexter lost the captaincy.

Overall, Dexter won 9, lost 7 and drew 14 of his 30 matches as captain. These are not bad figures, but do not necessarily suggest an inspiring or innovative leader. He failed to win key bouts like the 1964 Ashes and also became the first English captain to lose to India. Thus, while his personal record benefitted from the responsibility, it did not add to England’s wins.

Dexter’s theoretically-inclined approach also backfired when he was a selector. He dropped David Gower, who was in good nick and an aesthete at least equal to himself, from the 1993 squad for India upon the view that Gower was too ‘laid-back’ a cricketer to be of use. The theory was met with the sobering reality of a 3-0 whitewash at the hands of India.

Perhaps Dexter felt that managing to comprehend the skill, situation or method was enough and that the result did not necessarily matter as much. Indeed, he had retired at age 30, having played 62 tests. Later he said of his retirement, “I had been everywhere and what beckoned was repetition”.

What sort of legacy does this intellectual leave for English cricket? On the one hand, Dexter’s stylish stroke-play and personality upholds a joy of the game with an attitude that accepts personal success and failure in deference to a larger principle explored, while still marrying it with the necessary drive to overcome obstacles.

The attitude provided him with the requisite distance from the game which let him think intelligently about cricket’s potential; he was an early advocate of the one-day game, he helped set up the structure for the modern day ICC cricket ranking system and on his blog he extensively engaged for over a decade with matters such as corruption, batting and bowling styles, the decision review system (DRS) and the LBW rule and provided his thoughts on contemporary cricketers. All of these are products of an active mind, constantly furthering the dialogue on cricket.

On the other hand, the limitations of his approach were perhaps shown-up in his captaincy and selection. His theoretical disposition here could arguably be seen as rooted in colonial privilege.

The early 1960s, when Dexter was at his peak as a cricketer, was a period when the British Empire was coming to a tottering end. There was a sense of salvaging the rationality of Western thought, even as England's territorial control was diminishing faster than the Indian team’s twin batting collapses in the recent Headingley Test; a belief that, while physical occupation was no longer tenable, the ways of thinking were still relevant. The abstract ‘renaissance’ approach to the game that Dexter was associated with embodies that salvaging tendency; it divorces cricket from politics.

Also read: Reimagining Golf: Why the Game Needs To Adopt a More Exciting Format

The MCC supported Dexter as captain over a cricketer who may have proved the ideological opposite of Dexter as leader. For the 1962/63 Australian tour, where he batted admirably, Dexter was chosen to lead over his Sussex and England teammate David Sheppard due to the latter’s views on apartheid. Simon Wilde in England, The Biography: the story of English Cricket 1877-2018 writes “Sheppard’s anti-apartheid views were ultimately to scupper his candidature to lead the England side in Australia in 1962-63” with the former English fast bowler and then selector Gubby Allen having “acted to protect cricketing relations with South Africa”.

Sheppard, who was also a man of the cloth, was extremely vocal in his opposition to apartheid and in 1960, refused to captain the Duke of Norfolk’s XI against the touring South African team as a mark of protest. Dexter averaged 57 when playing in South Africa, while Sheppard never played in the country. This is not to suggest that Dexter lost humanity in pursuing abstraction or batting skill. He championed women’s equality in cricket and tennis.

Yet, to examine his legacy today when England and South Africa seem to be going through introspection on racial discrimination in cricket, all aspects of Dexter’s career are important to cricketing history. Indeed, one wonders whether the late cricketer would have brought to bear the same intellect to the matter of race as he did, say, to the ‘Umpire’s call’.

I wish I had seen the magnificence of Dexter live and no amount of politics can ever take that feeling away. However, as the ever relevant C.L.R. James reminds us, “...what do they know of cricket who only cricket know”. Perhaps there is that necessity to know more as a cricket fan.

To contemplate Dexter’s cricket legacy, one must know to look past both his formidable statistics and his batting genius. As cricketers today speak about racism and its impact on their careers, grace and grit must mean much more than a blazing square-cut. Perhaps that reminder needs to be part of Dexter’s legacy as well.

Anushrut Ramakrishnan Agrwaal is a doctoral student in film history at St Andrews University.

This article went live on September first, two thousand twenty one, at zero minutes past one in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.