Vaibhav Sooryavanshi’s Moment in the IPL Sun, and Why It’s Tough Being a Boy In a Man’s World

Two stories here: the fairytale century of 14-year-old Vaibhav Sooryavanshi, who exploded like a Diwali firecracker, nothing less; and the response of Indian fans and cricket columnists.

The IPL was only three years old when Sooryavanshi (his surname translates as one who traces their lineage back to the sun) was born in 2011. In December 2024, he caught everyone’s attention when he was bought by Rajasthan Royals (RR) in the auction for Rs 1.1 crore (approximately $130,000) at the ripe old age of 13.

At his age, the CV is not going to run into several pages. It’s a short bio: an unbeaten triple century in a local inter-district tournament in Bihar, the state he hails from; a 58-ball century against the Australian under-19 team in a four-day game; and the under-19 Asia Cup last year, where he scored 176 runs at an average of 44.

According to Sooryavanshi’s childhood coach, Manoj Ojha, it was V.V.S. Laxman, currently head of the National Cricket Academy, who picked him for an under-19 quadrangular tournament. When Sooryavanshi got run out at 36 in a match, he broke down in tears. Laxman told him: “We don’t only see the runs here. We see the people who have the skill for the long run.”

So, Sooryavanshi comes into the IPL with an unprecedented buzz around him, and launches his adult career with a nonchalant six. No blinking – see ball, hit ball.

In only his third match, he reaches his century with a six (no pottering around on 94), an innings of 101 off 38 balls, which featured 11 sixes and seven fours – 94 of his runs came in boundaries. He went from 50 to 100 in ten minutes flat.

Records were broken: the southpaw became the youngest player to score a century in T20 cricket; it was the second-fastest IPL century after the Caribbean great, Chris Gayle.

Rahul Dravid (his coach at RR) and Sachin Tendulkar agreed upon Sooryavanshi’s strengths: a fearless approach, bat speed, high back lift, transferring the energy behind the ball and picking the length really early.

The word ‘temperament’ is used often in the world of cricket. What we glimpsed of it was impeccable. Sooryavanshi’s celebration was short, unexuberant and effortlessly stylish – a quick touch of the bat to his helmet, an understated salute (with a hint of swag) that will be remembered.

In the post-match interview his quiet confidence shone through; there was little display of emotion; the pumping endorphins sublimated into a boyish smile – Vaibhav seemed to be saying: I knew this all along; why are you all so surprised?

It was the interviewer, the usually composed former India spinner Murali Kartik, who seemed overwhelmed and at a loss for words, mumbling something about ‘ladka’ and ‘aadmi’, boy and man.

Vaibhav’s sixes were awe-inspiring but as a cricketer he seemed hardly awed by the occasion or the milestones he had achieved.

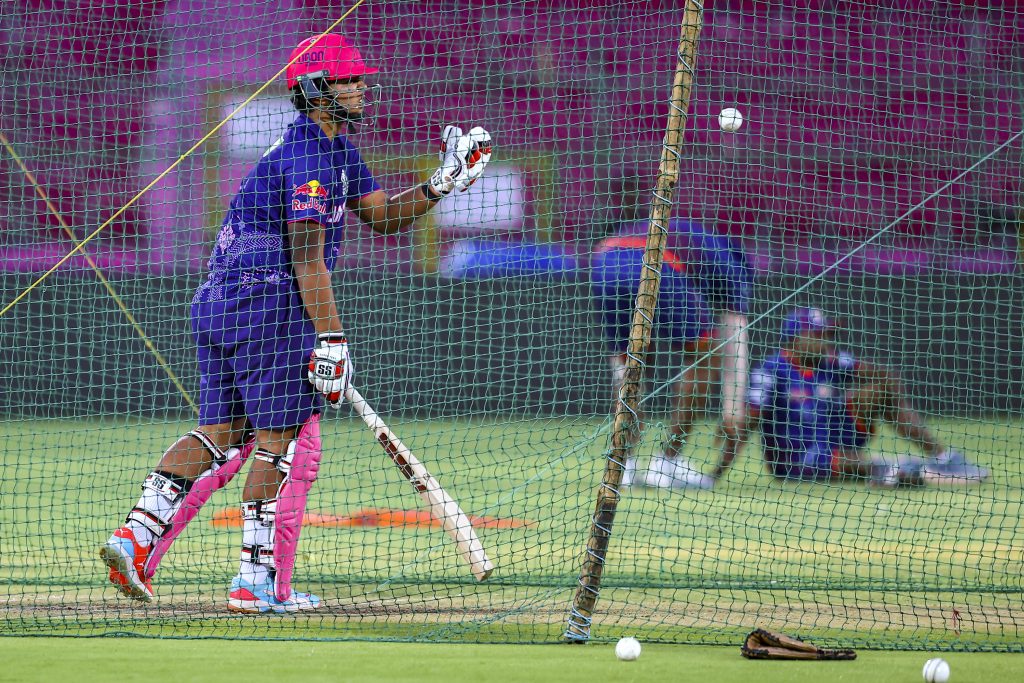

It’s tough being a boy in a man’s world, even if one has just slaughtered the world’s best bowlers in the world’s premier T20 tournament. Sooryavanshi during a practice session in Jaipur. Photo: PTI.

§

The response of the fanatical Indian fan on social media was revealing. Prithvi Shaw trended on X. Prithvi Shaw! In this glorious once-in-a-lifetime moment, when a one-in-a-billion player became a worldwide sensation, the churlish Indian fan was thinking of failure.

For those unfamiliar with the name, Shaw is a Mumbai player who came into international cricket with similar hype, but failed to live up to it. He went unsold in the current IPL season. Poor Shaw – he still might make a comeback: he’s only 25.

A section of fans sounded a warning that Sooryavanshi might well go downhill like Shaw; others questioned his age: he doesn’t look 14; still others counted the number of mis-hits in Sooryavanshi’s innings. It’s tough being a boy in a man’s world.

The cynicism reveals something about national character. The jokes one tells are reflective of the society one inhabits.

A well-worn oft-told Indian joke goes something like this: there was once an international crab championship, in which all the countries of the world sent their crabs to compete. Someone noticed that the stall from India had a huge box, but it had been left open – there was no lid on it. What if they escape? When asked, the Indian representative explained: “These are Indian crabs. They don’t need a lid. They are too busy pulling each other down.”

It’s not just Indians though. Scepticism has been voiced in non-Indian quarters as well. After the auction in December, when Sooryavanshi got picked up, Jonathan Liew, in his piece for The Guardian, dug out the names of previous wildcard players who came a cropper, like Prayas Ray Burman, a 16-year-old leg spinner picked by Kolkata Knight Riders (KKR) in the 2019 auction for £139,000:

“He made his debut in that year’s tournament, was destroyed by Jonny Bairstow, went for 56 off his four overs. Never played again … was discarded at the end of the season and forced to return to college.”

Liew also mentions Ramesh Kumar, signed by KKR in 2022: “Despite not having played any kind of representative cricket … He was not retained by KKR and if he’s played any kind of official cricket since, nobody has recorded it.”

I get Liew’s point, but the negativity seems presumptuous, especially if you haven’t seen Suryavanshi play. In any sport, there will be those who make it and those who don’t – why name and shame those who didn’t, then use those names to cast a cynical eye on a new discovery?

After Sooryavanshi’s century, Australian Robert ‘Crash’ Craddock, a senior sports journalist, lamented: “It’s goodbye forever to those anonymous games of cricket down the park with his school buddies, to roaming around his city without being noticed. Is that a good thing? We shall see.”

As I said earlier, it’s tough being a boy in a man’s world, even if one has just slaughtered the world’s best bowlers in the world’s premier T20 tournament. If nothing else, just give the boy credit for holding his nerve in front of a packed stadium, instead of worrying about his lost childhood. Prodigies are not that unknown in the arts and sports. Nadia Comaneci became the first gymnast to be awarded a perfect score of 10.0 at the 1976 Montreal Olympics. She was 14.

There was also a less insidious strand of response to Sooryavanshi’s ton, which went along the lines of: what was I doing at 14? What were you doing at that age? What’s my kid doing?” People forget that it’s not about you, me, us – it’s about him. Gazing at one’s own navel is beside the point.

Also read | Cricket’s Illusion: A Republic Divided by a Game

§

In India’s deeply hierarchical society, already divided along caste and class lines, Sooryavanshi’s success has upset the senior-junior equation. Kids are supposed to know their place. The one who is older is superior just by virtue of being older in age: the whole Asian thing of ‘respect your elders’. Here comes a kid who has shown adults their place. It’s difficult to stomach.

Not that Sooryavanshi is not showing ‘respect’, a word so overused in India that it has lost its meaning. Going through the motions of what is considered ‘showing respect’ is confused with respect itself.

Sooryavanshi showed respect to his parents: “My mother used to sleep for three hours, wake up at 2 am, prepare food for me. My father quit his job, my elder brother took over the job. We had limited means, but my father backed me to succeed. Whatever results you are seeing today, my success is all because of my parents.”

He’s also been touching the feet of his elders: M.S. Dhoni’s at a post-match presentation in Guwahati, and of the owner of the RR franchise after his century. Which made me think – would I touch the feet of my publisher if he bought my book in a bidding war, and the novel won the Booker? Probably not.

Jokes apart, what does the success of players like Sooryavanshi bode for the IPL, and T20 cricket in general?

For one, the IPL has made cricket a viable career option. Earlier, when Sunil Gavaskar and Kapil Dev were playing Test cricket, it was considered more of a calling, with average pay. Now, it’s like a competitive exam for which thousands apply, just like engineering, medicine or the civil services.

The key takeaway for the IPL itself, the way the game has been played up until now, is that, perhaps, these might be remembered as the glory days when babies and grandfathers played in the same league. Dhoni is 44, while Sooryavanshi is 14.

Presently, many retired players play the tournament, which might change with younger and even younger cricketers coming in. They have a different approach to the T20 format. The game changes every day. Why play with half-steam players when you can have young blood playing with optimal strength? Older players, bar the odd exception, might be pushed out, relegated to the veteran’s league.

The IPL might become no country for old men. Thirty could become the new cut-off age.

Then again, the IPL is a distinctively Indian mix of nostalgia and aspiration. Indian fans like it that way. Stadiums around the country explode in a sonic boom each time Dhoni walks in to bat. At the same time, we also like to watch new stars being born, plucked out of dusty obscurity in a country where few have opportunities for upward mobility and talent is routinely squashed by the system.

We approve of the blend of youth and experience under one roof -- much like the joint family at home.

For the moment, the IPL TV spots are inclusive, promoting Sooryavanshi’s next few games as a match-up: Protege vs GOAT (greatest of all time), whoever the legend might be.

Meanwhile cricket, always, is the greatest leveller. In his very next innings, Sooryavanshi was out for a golden duck.

The writer is the author of The Butterfly Generation: A Personal Journey into the Passions and Follies of India’s Technicolor Youth, and the editor of House Spirit: Drinking in India.

This article went live on May fourth, two thousand twenty five, at twenty-two minutes past twelve at noon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.