‘Your Personal Mobile Number Is No Longer Yours’: How Art Is Demystifying Technology for the Masses

India is rapidly digitising. There are good things and bad, speed-bumps on the way and caveats to be mindful of. The weekly column Terminal focuses on all that is connected and is not – on digital issues, policy, ideas and themes dominating the conversation in India and the world.

It has always been a challenge to communicate various issues associated with technology and its effects on society to the public. In a post-truth world where people are not known to talk facts but promote myths like nanochips in our currency notes, it is indeed important to demystify technology.

Art can be an important ally in communicating messages when engineers, social scientists, and media fail. Last week, an art exhibition in Goa by the Bachchao Project attempted to address some of these concerns through their exhibition on 'Data: Public Private and Beyond'.

Inspired by the exhibition of 'The Glass Room', where art was used to decipher the invisible black boxes of technology, the Bachchao Project attempted something similar.

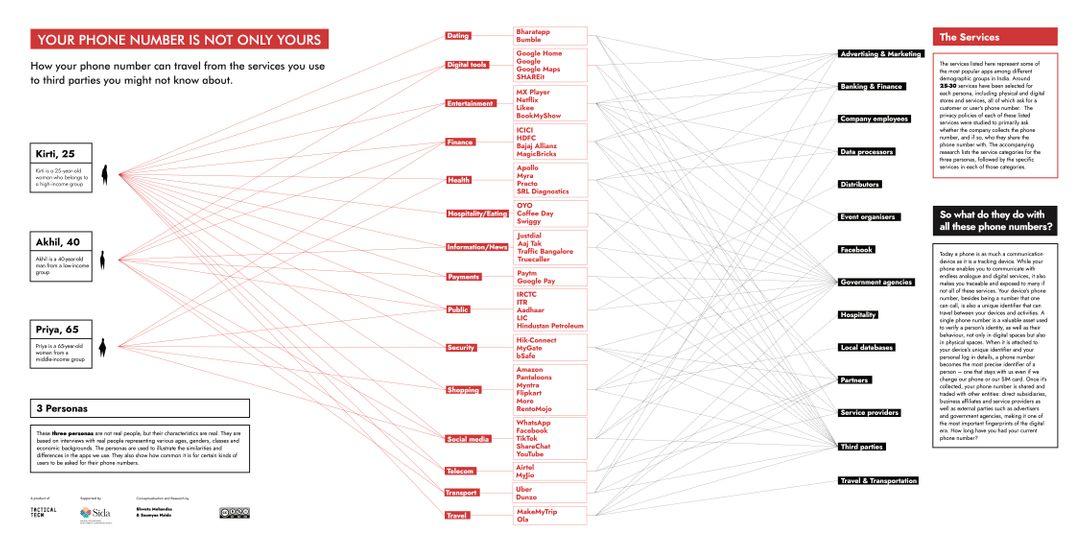

Some of 'The Glass Room' artwork also explained how our personal mobile number is no longer ours.

At the heart of the attraction was the 'See No Evil' artwork by Thomas Louis, a potter who chose to express his artwork with the inspiration from the three wise monkeys.

Thomas explained how he visualised the surveillance cameras as these are objects, which don’t always function when they are required to. Comparing surveillance cameras with the hands of the monkeys, he shaped the cameras as langurs.

Photo: The Bachao Project, CC BY SA

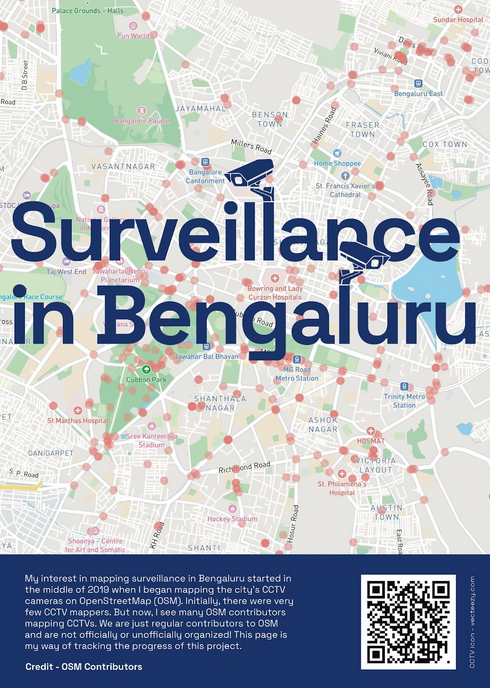

In his photo essay on 'Surveillance in Bengaluru', Thejesh G.N., a long-time OpenStreetMap contributor and part of the data communities in India, explained how ubiquitous the nature of surveillance cameras is and the purposes for which they are being used.

With a series of newspaper clippings beside the cameras, Thejesh's work focussed on the various challenges that arise because of the cameras.

In the photo essay, there's a digital component, where one can use a QR code to scan and interact with the real-time mapping of surveillance cameras. The map is available on his website. He also offers a guide on how to map cameras on the OpenStreetMap project.

Photo: Thejesh G.N., CC BY SA

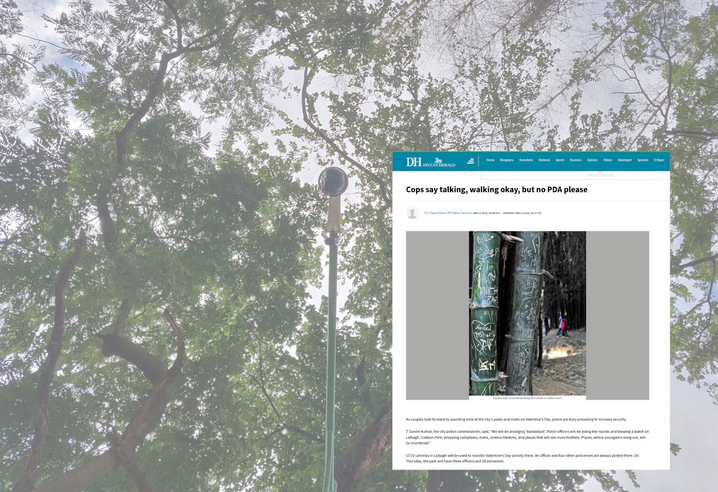

The cameras are watching us all the time, taking our space to even express any form of affection in parks and public spaces.

Photo: Thejesh G.N., CC BY SA

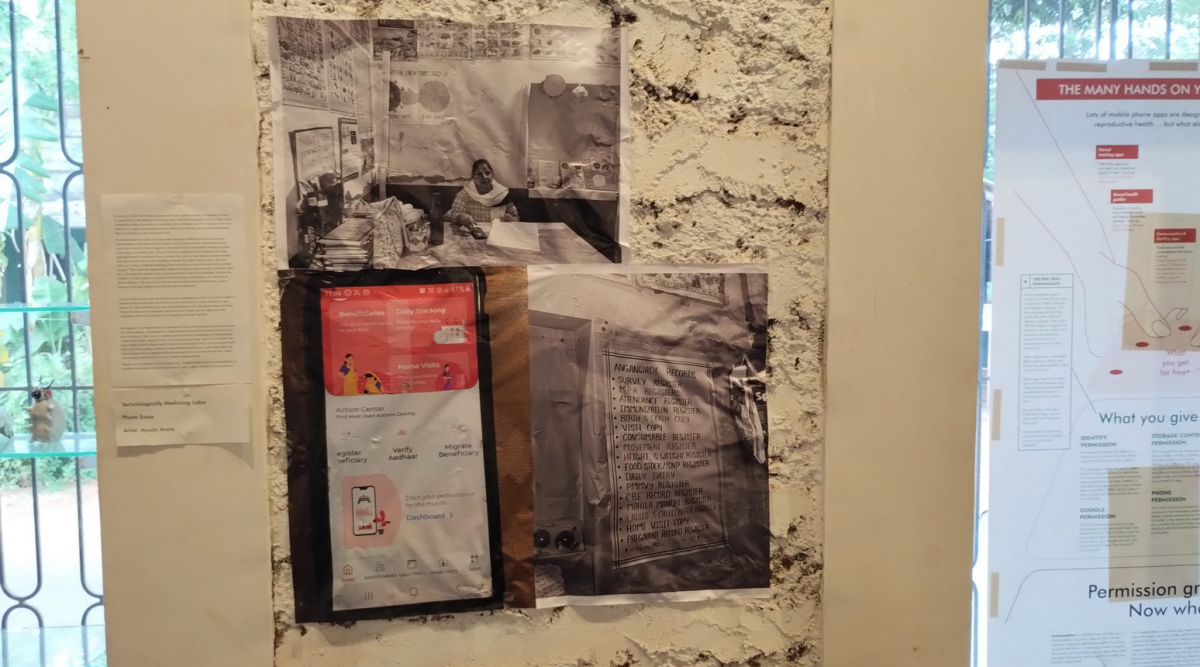

In another photo essay, 'Technologically Mediating Labour', Ayushi Arora showed how technology plays a role in anganwadi workers' life. The work of anganwadi workers has been transformed with apps taking over the role of record keeping, where traditional records have been replaced by databases.

Ayushi showed how apps like the Poshan Tracker are quantifying labour and how the work of anganwadi workers is being surveilled through quantified performance dashboards.

Photo: The Bachao Project, CC BY SA

In 'Watching You Watching Me: an allegory of desire, data and dread, as I age alongside the interweb', artist Oish explored how data is used to watch people.

Although our data being accessible online creates a sense of belonging, it also raises concerns over how the data is going to be used. This makes us think about how we are forced, and at the same time concerned, to share data online.

In 'Bodies of dissent: exploring data, intimacy and disability on dating apps', artists Nu and Ritika of Revival Disability India explored how data can reveal information on dating apps. For disabled people, it's a challenge to reveal or hide this information on dating apps. Through a booklet, they explore the idea of an ideal dating platform which would make online dating apps safer for people with disabilities.

Photo: The Bachao Project, CC BY SA

Each of these artists explored technology in different ways that are necessary for us to understand and introspect their usage. I hope to see more of these artworks in future. Some of “The Glass Room” artwork was also on display at the art exhibition explaining how our personal mobile number is no more ours.

Your phone number is not only yours. Photo: Shweta Mohandas and Saumyaa Naidu, CC BY NC ND

Srinivas Kodali is a researcher on digitisation and hacktivist.

This article went live on May twenty-second, two thousand twenty three, at fifteen minutes past six in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.