Telecommunications Bill Lays the Ground for Totalitarian Control of the Internet

The Telecommunications Bill 2023 that has been introduced in parliament this session is an extremely draconian law. It forces government control on every message that is being transmitted, emitted or received in any form including wired, electronic, optical etc. The definition of a message in the Bill is very broad with inclusion of sign, signal, writing, text, image, sound, video, data stream, intelligence or information sent through telecommunication. This is so vast that every internet/digital app within the boundaries of India has to comply under the upcoming law.

The Bill is creating a new authorisation regime, where any telecommunication service would have to apply for authorisation to operate in India. With the wide definition of telecommunication and messages, this will ideally be applicable to every social media application out there – WhatsApp, Facebook, X, Instagram, etc. This Bill essentially brings a licence regime to the internet. Services not complying with the law could be likely to be blocked or banned in India, like TikTok was.

The Internet and Mobile Association of India, a leading industry body of internet companies and startups in the country, has welcomed the Bill for removing over-the-top platforms (OTTs) from being regulated. But this is probably a false sense of celebration, as this Bill will have a profound impact on every internet company with the authorisation regime and the compliance requirements under it.

The Internet and Mobile Association of India, a leading industry body of internet companies and startups in the country, has welcomed the Bill for removing over-the-top platforms (OTTs) from being regulated. But this is probably a false sense of celebration, as this Bill will have a profound impact on every internet company with the authorisation regime and the compliance requirements under it.

The Telecommunications Bill 2023 will replace colonial laws of the Indian Telegraph Act 1885 and Indian Wireless Telegraphy Act 1933. These colonial laws provided extreme forms of control over communications in colonial India to the British. While the Bill is being praised by the telecom industry for replacing archaic colonial laws, the Telecommunication Bill 2023 is expected to provide a larger control than these colonial laws to the Government of India and its institutions.

The provisions of the Bill allow the Union government or a state government to take over any telecommunication service or network in the event of public emergency or safety. It allows officials of both Union and state governments to intercept or detain or not to transmit messages from a single person or class of persons. This single measure gives officials immense powers to control and spy on every message over the entire telecom network for public safety.

The Bill further mandates biometric verification of every social media user by the telecommunication services. This forces identification for all forms of communications and pushes India’s KYC regime across the internet. To illustrate the power of these provisions, think of the Delhi Police trying to access all the details of every individual tweeting during the farmers' protest, to stop every message with a certain hashtag or keyword or to block people from accessing their own accounts. Every aspect of this Bill allows the police or intelligence agencies to continuously monitor the opposition, whether it is farmers' leaders or students who might be protesting.

While the Bill provides exemptions for accredited media professionals to not be intercepted or detained, it would require every journalist to identify themselves as such with the telecom service companies. Journalists would have to register with every telecom service provider including social media and other communication services. But this may not necessarily provide them with the media freedoms and privacy that are required in a democracy.

The push for KYC for internet apps and services began with the CERT-In rules mandating KYC and logging for VPN companies in India. With the Telecom Bill, this architecture of an identity-linked internet telecommunication service will kill anonymity online. This in itself is not against the fundamental right to privacy, as the Puttaswamy Vs Union of India fundamental right to privacy judgment recognises exemptions for national security and doesn’t grant Indians the right of anonymity. However, there is no conducive environment to even challenge these upcoming surveillance laws in courts, with a majoritarian executive that is able to force these laws without any obstacles.

The Bill includes all these provisions for detention of messages as an alternative to avoid internet shutdowns and look for alternate mechanisms on the recommendation of the Parliamentary Committee on Information Technology. The issue of access to internet is the core of telecommunications infrastructure. To address issues of access to remote areas, satellite based internet was been explored as an alternative. The spectrum allocation for this is going to be controversial, with the need for auctions vs administrative allocation for limited scenarios. The Supreme Court judgement on spectrum allocation would be revisited. It is important to note, spectrum allocation using administrative approvals alone could lead to illegal allocations and scams without due process.

While these are provisions merely provided for public safety, the national security provisions of the Bill allow the Union government to suspend, remove or prohibit the use of specified telecommunication equipment and telecommunication services from countries or persons as may be notified. So like TikTok being banned, similar communication and media applications can be blocked from countries or individuals at large.

The national security provisions also allow the Union government to dictate telecom standards for equipment and services including, encryption, cybersecurity and data processing in communication. The security standards for telecommunications equipment are indeed important and can be detrimental to national security if the Government of India has no control over them. This needs to be seen with the geopolitical controversies across the world of not allowing Chinese companies like Huawei and ZTE to build 5G infrastructure. India too doesn’t want any Chinese equipment as part of its telecommunications infrastructure.

The problem of encryption standards for telecommunication services being set by the government could be dangerous, given the Government of India’s interest to break up encryption of WhatsApp and Signal messengers. Most internet communication is encrypted and is increasingly being pushed towards encryption, to evade nation state surveillance programmes. Meta has recently moved all of its messaging services from Facebook Messenger and Instagram to end-to-end encryption, using the Signal protocol.

India’s strategy with censorship and surveillance is to push for identification and control of communication networks. As the saying goes, there is freedom of speech in India, but there is no guarantee of freedom after speech. India’s censorship strategy is to shut people down by punishing a few outspoken and hoping the rest fall in.

The Telecommunications Bill demands a Chinese-style banning of messages based on keywords or other characteristics. Its usage, though, will be limited to scenarios like the case of a public emergency such as protests and riots, instead of a continuous censorship that exists in China. While this difference might exist, it still lays the ground for a larger totalitarian control if the government wants to eventually assert control.

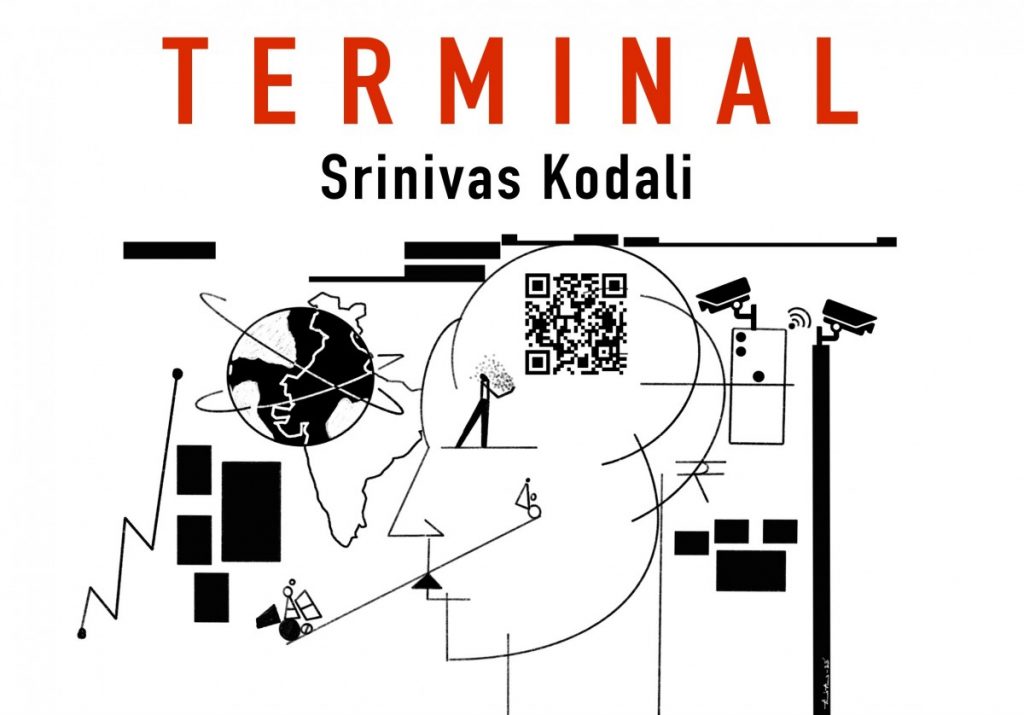

India is rapidly digitising. There are good things and bad, speed-bumps on the way and caveats to be mindful of. The weekly column Terminal focuses on all that is connected and is not – on digital issues, policy, ideas and themes dominating the conversation in India and the world.

Srinivas Kodali is a researcher on digitisation and a hacktivist.

This article went live on December twentieth, two thousand twenty three, at zero minutes past ten in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.