From ‘Joy-Giver’ to Antidote: Cannabis Consumption in India

“The five kingdoms of plants, having soma as their chief, we address: the darbha, hemp, barley, saha – let them free us from distress.” This quote from the Atharva-Veda (1200-900 BCE) reveals the long history of the belief in the potent abilities of plants like cannabis in relieving discomfort and illness.

Indigenous to the Indian subcontinent, cannabis grows abundantly in the Himalayas and northern parts of South Asia. The use of cannabis has been referred to in some of the oldest scriptures including the sacred Vedas from around 1500 to 900 BCE, where it was described using words such as “joy-giver,” “victory” and “liberator” in Sanskrit. In other ancient literary sources such as Sarangadhara (1500 CE) and Bhavapakash (1600 CE), its properties have been described as ranging from curing leprosy to producing euphoria. The Vishnu Purana, a key Hindu scripture, speaks about how the devas (gods) and rakshasas (monsters) churned the ocean to obtain amrita (a drink to immortality). When a lethal poison (Halahala) emerged from the ocean and threatened to destroy all creation, Shiva drank it to protect the world. According to popular lore, he relieved the pain caused by the poison by consuming cannabis seeds and leaves. Ever since, cannabis has been associated with Shiva and his devotees.

Opium Smokers Served Fruit and Bread; Mughal, India; c. 1750; Colour on paper; 18.5 x 29 cm. Image courtesy of Cleveland Museum of Art.

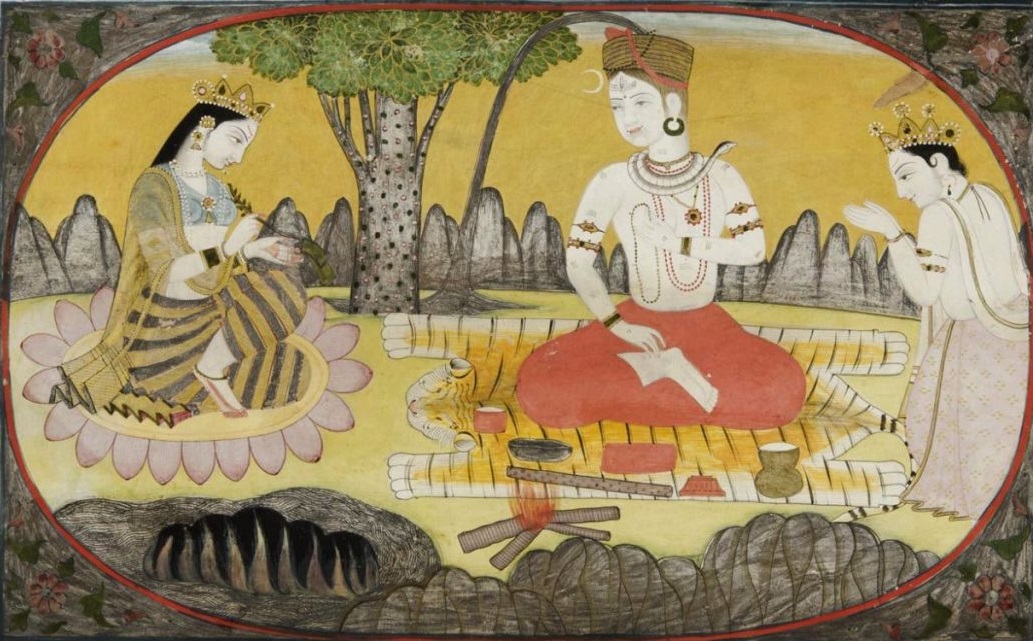

We see several illustrations of the consumption and preparation of cannabis in Indian miniature paintings, including multiple images of Shiva and Parvati preparing bhang, a milkshake-like drink containing cannabis. Over time, satirical scenes of dissolute drug-takers became a common genre in Mughal paintings. Multiple paintings depict scenes of men engaging in the consumption and preparation of bhang. Other images portray groups of figures depicted in various stages of intoxication and inebriation.

Raja Sidh Sen of Mandi Offering a Bowl of Bhang to Shiva; Master of the Court at Mandi, Punjab Hills, India; c. 1711–1725; Opaque watercolour on paper; 25.4 x 16.2 cm. Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Cannabis consumption in India became an important topic of discussion in the seventeenth century, under the colonial administration, when British travellers and merchants were introduced to the intoxicating effects of bhang for the first time. Arriving in the port city of Machilipatnam, Thomas Bowry, a merchant of the East India Company, was one of the first European officials to draw attention to the widespread use of cannabis. In his travel accounts, he writes about the experiences of his and his colleagues resolving to try it themselves, both recreationally and with the intent of commodifying it. A painting by John Greenwood from 1755 imagines a scene of European sea captains seated around a table, inebriated under the influence of bhang.

Preparing Shiva’s Drink; c. 1840; Opaque watercolour on paper; 12.7 x 20.8 cm. Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Even as the English officials and merchants in Asia were consuming the drug, there remained a stigma around its consumption. At the same time, there were other figures who advocated for its medicinal properties. Assessing the virtues of the drug came to be one of the signature goals of the Royal Society, London. A key figure in these efforts was Robert Knox. In the 1670s, Knox had fled from years of captivity in the kingdom of Kandy in Sri Lanka. Undertaking an arduous journey through hostile territory to escape, Knox concluded that he would have died were it not for the anti-nausea effects of cannabis. After Knox safely returned to London in 1680, he worked with the British scientist Robert Hooke in attempting to destigmatise its use in their home country. On December 18, 1689, Hooke delivered a lecture to the Royal Society presenting a positive assessment of cannabis consumption. Hooke concluded by noting that he was currently attempting to grow the seeds in London, and that “if it can be here produced” the plant could “prove as considerable a medicine in drugs, as any that is brought from the Indies.” Despite these assessments, the colonial government remained critical of its use. In 1798, the British Parliament enacted a tax on bhang, ganja and charas, intending to reduce cannabis consumption “for the sake of the natives’ good health and sanity.”

Sea Captains Carousing in Suriname; John Greenwood; c. 1755–58; Oil on bed ticking; 95.9 x 190.5 cm. Image courtesy of Saint Louis Art Museum.

Today, along with its continued recreational use, the consumption of cannabis continues to be intertwined with the social and spiritual landscape of the Indian subcontinent. While the possession of cannabis is illegal in India, the preparation and sale of bhang is legal in certain states. Bhang continues to have a cultural significance in Hindu rituals, is frequently consumed and offered to deities as part of festivities and is popularly consumed by ascetics and mendicants.

Khushmi Mehta (she/her) holds a bachelor’s in Visual and Critical Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and is currently pursuing a PhD in Art History from the Graduate Center, CUNY. Her research interests include issues of decolonisation, archive formations, and art historical pedagogy. She is based in New York City and currently works at the Newark Museum of Art. She previously worked as the Research Editor at the MAP Academy.

This article was originally published by the MAP Academy, an open-access online resource focused on South Asian art and cultural histories.

This article went live on November second, two thousand twenty five, at zero minutes past nine in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.