How the Company School of Paintings Interpreted India for the Raj

The images that will follow are from A Treasury of Life an exhibition of Indian Company Paintings (1790-1835) being held by the DAG. The exhibition is on till July 5, 2025. These paintings were made by Indian masters commissioned by the East India Company and were for long on the margins of Indian art history. They range from paintings of flora and fauna to Indian structures and design and also images of 'native' life.

The images are interspersed with text from an excerpt from the introductory essay by Giles Tillotson on 'The Appreciation of Company Paintings'.

A problem that has beset Company painting throughout this time has been the term itself. The curator and the contributors to Forgotten Masters argued with some force that calling it ‘Company painting’ puts too much emphasis on the patrons who commissioned it, and not enough on the artists who created it, who were waiting to be rediscovered and brought into the limelight.

Unidentified Artist (Company School), Oriental Garden Lizard (Calotes versicolor), Opaque watercolour on paper, c. 1827, 8.7 × 7.2 in.

One contributor, Henry Noltie, argued that any single term was too restrictive to capture the range of styles practised in this period by artists working across the subcontinent. This last objection was ill-founded: the term ‘Company painting’ was never intended as a stylistic category, so the criticism charges it with failure in a task that no one ever set it.

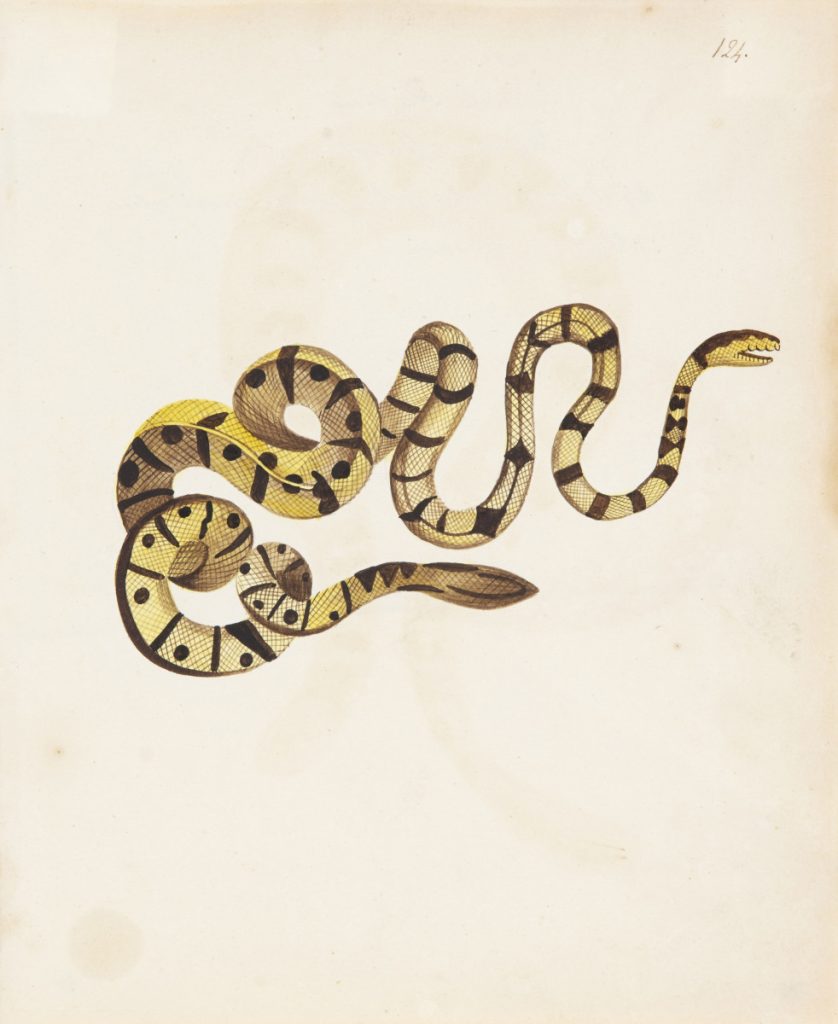

Unidentified Artist (Company School), Yellow Bellied Sea Snake (Hydrophis spiralis), Watercolour on paper, c. 1820, 8.7 × 7.2 in.

It is true that the Urdu term kampani qalam points to a style (as qalam means ‘pen’) but early authors on Company painting did not use the English term in that way. The various schools of Company painting are indeed stylistically very diverse (as we will see from the works in this exhibition). What they have in common is that all the artists were working for foreign patrons; and that is what the term aims to capture.

Unidentified Artist (Chinese Trade School), Custard Apple (Annona squamosa), Opaque watercolour on paper, c. 1825, 15.0 × 19.2 in.

Most painting made in India in the pre-modern era is either court painting (i.e., commissioned at one of India’s many royal courts) or temple painting (i.e., commissioned by the priests and administrators of temples and monasteries). No one complains that the term ‘court painting’ fails to capture the diversity of art produced at court. Of course, we all recognise that it cannot hope to do that; it merely points to where it originates.

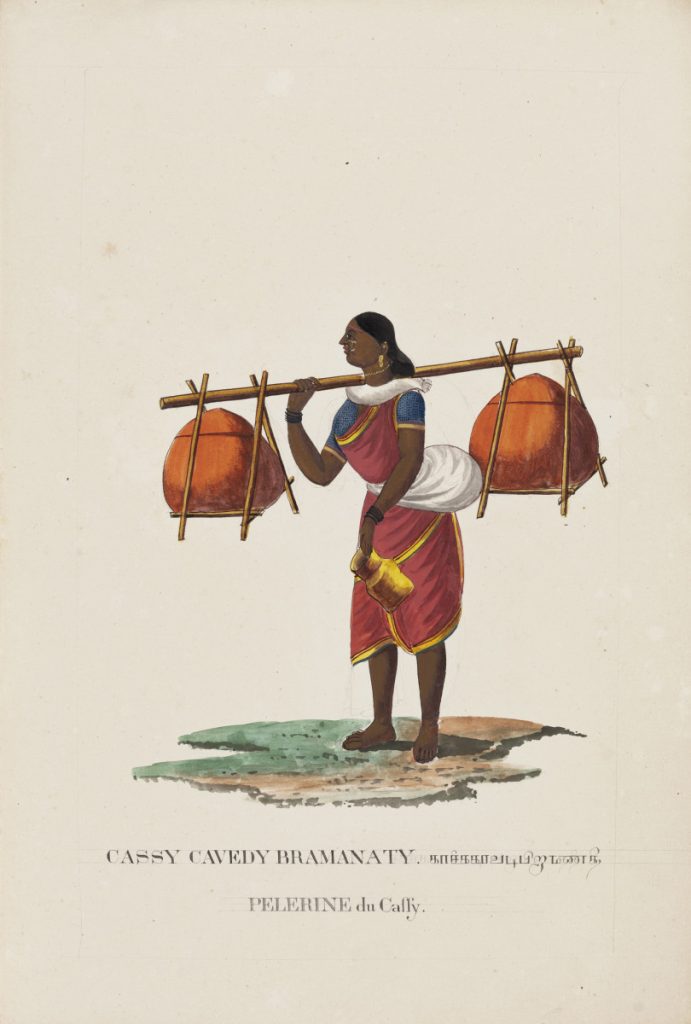

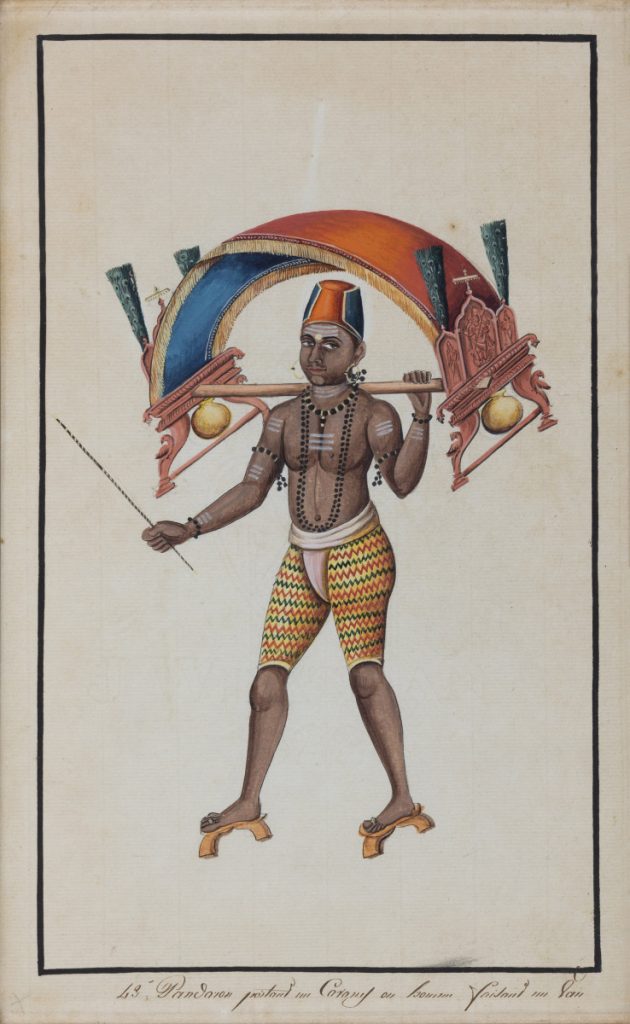

Madras Artist (Company School), Cassy Cavedy Bramanaty / Pelerine du Cassy [Kashi Pilgrim, Kavadi Brahmin], Opaque watercolour on paper, c. 1800, 17.2 × 11.5 in.

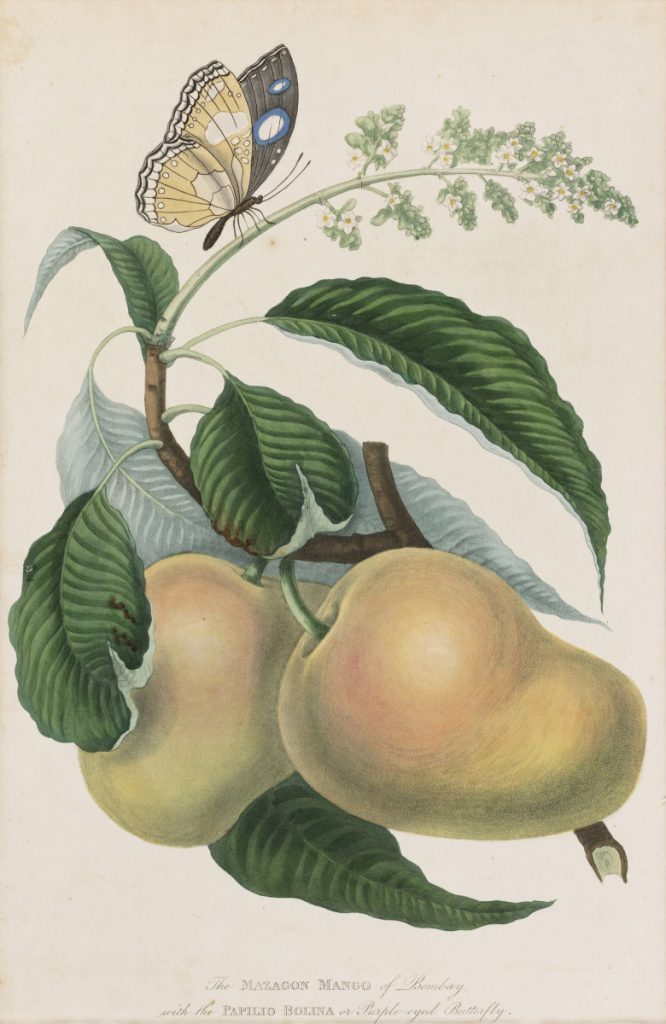

James Forbes, The Mazagon Mango of Bombay with the Papilio Bolina or Purple-eyed Butterfly, Etching and aquatint, tinted with watercolour on paper, 1768, Print size: 11.0 × 7.0 in., Paper size: 11.7 × 9.0 in.

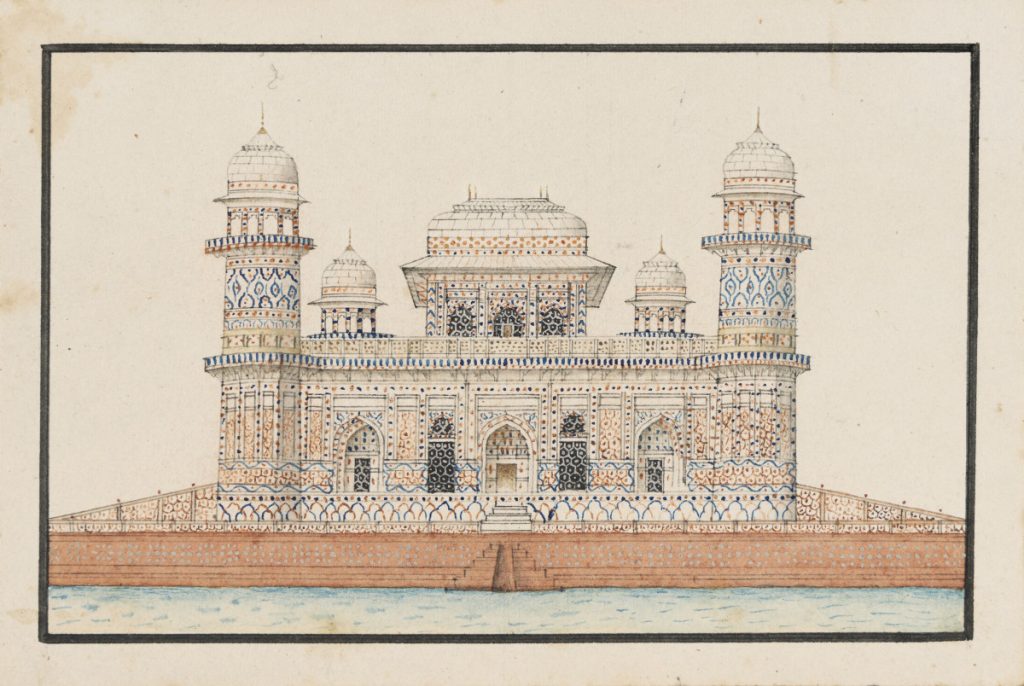

The subject matter of Company painting is very diverse, but falls into three main categories: natural history, including botanical studies; architecture, including views of historical monuments, and scenic views of towns and landscapes; and Indian manners and customs. This last category includes images of people who represent specific castes or trades; depictions of people engaged in religious rites and rituals; and, last but not least, depictions of popular sacred idols.

Agra Artist (Company School), The Mausoleum of I’tima¯d-ud-Daulah, Watercolour on paper, c. 1836, 3.0 × 4.5 in.

The focus on these three subject areas reflects European engagement with their Indian environment in an attempt to come to terms with all that was unfamiliar to Western eyes. Europeans living in India were delighted to encounter flora and fauna that were new to them, and ancient buildings in exotic styles. They met (or at least observed) multitudes of peoples whose dress and habits were strange but – as they began to discern – were linked to systems of religious belief and social practice. They turned to Indian artists to help them assimilate all this new material, to represent it, to order it on paper.

Chuni Lal (Patna Artist), Details of Pietra Dura Inlay, Taj Mahal, Opaque watercolour and ink on paper laid on paper, c. 1835, 7.2 × 11.5 in.

This explanation of Company painting would suggest that its primary motivating force was foreign: that it is the product of Western minds reacting to Asia, with a desire to explain it on their own terms. It is, in short, a classic case of Orientalism. The very timing of its inception confirms this. There are very few examples of Europeans commissioning works from Indian artists in the first century and a half following the establishment of the trading companies (i.e., from 1600 to 1750, in the period of Mughal rule).

Tanjore Artist (Company School), A Pilgrim Carrying a Wood Kavati, Opaque watercolour on paper, c. 1822, 15.0 × 9.5 in.

The rise of Company painting coincides with the expansion of the power and influence of the companies (especially the British East India Company) in the second half of the eighteenth century, following such decisive battles as Plassey (1757), Buxar (1764), Srirangapatna (1799) and Delhi (1803). Company painting, as a reflection of the Western gaze, advanced hand in hand with the Company’s territorial expansion.

Captain Charles Gold, A Sepoy of Tippoo Sultaun’s regular Infantry, Aquatint, tinted with watercolour on paper, 1799, Print size: 11.5 × 8.7 in., Paper size: 13.0 × 10.0 in.

Giles Tillotson is a writer and lecturer on Indian history and architecture.

This article went live on May twenty-fifth, two thousand twenty five, at fifty-five minutes past eleven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.