Toying With Gandhi: A Compilation of Moods, Mysteries and Meanings

French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss had coined the term floating signifier to denote an entity that represented “an undetermined quantity of signification, in itself void of meaning and thus apt to receive any meaning”. Lévi-Strauss had used words like “mana” and “oomph” as examples of floating signifiers that can ostensibly incorporate a wide range of connotations.

Over the years, with the distortion of vocabulary and the decadence of culture, the idea of meaning itself has become elastic. Numerous words, emotions and ideas have started meaning different things to different people. From love to nationalism to practically the entire gamut of American slang, additions to the list of floating signifiers have steadily increased since Lévi-Strauss identified the first few.

In expanding the range of these signifiers, India has had a peculiar contribution. It provided the world its first floating signifier – one which is not a word, an emotion, or an idea, but a human being.

A human being called Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

Whenever India, or rather, its politicians, have required a stand-in for a slogan, a face for a campaign or scheme, or an embodiment of a supposedly Indian virtue, Gandhi has been ever available. Icons in other parts of the world generally live on through their messages or their missions, successful or otherwise. Gandhi has lived on through both, as well as his malleability.

“Gandhi has always been used as a tool by those that wield power to say whatever they want to say. Politicians in India have never shown any interest in Gandhi’s ideas. They have only been interested in appropriating his image, his quotes and his accessories,” says Debanjan Roy, a 48-year-old visual artist and sculptor based in Kolkata.

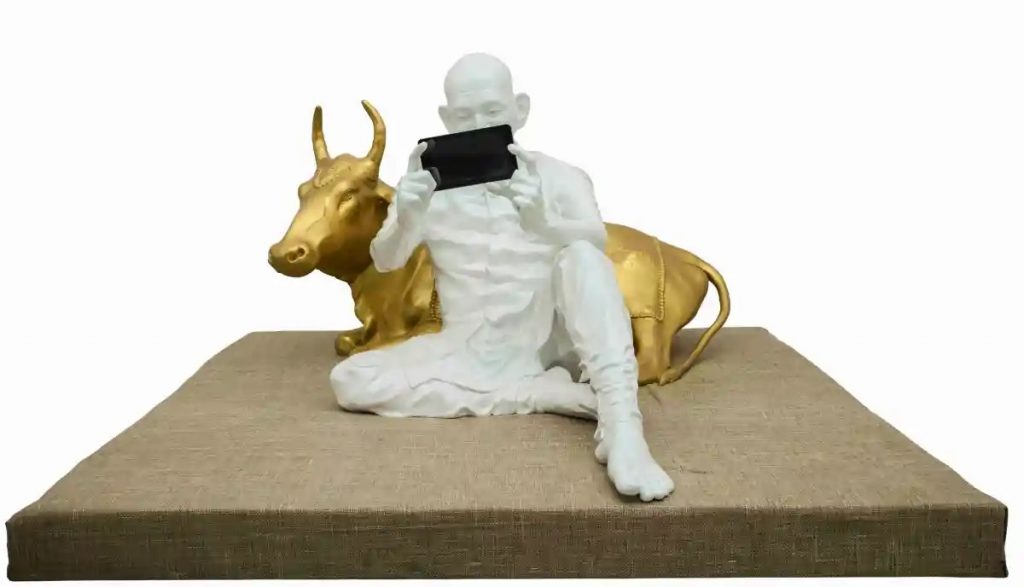

Photo courtesy: Akar Prakar and the artist Debanjan Roy

Roy, known for subtlety and cheekiness in his work, has been fascinated by Gandhi for as long as he can remember. His latest exhibition, hosted by Akar Prakar, Roy, an alumnus of Rabindra Bharati University, has captured Gandhi in ways few could have imagined.

In a series of fibreglass sculptures that look and feel like life-sized toys, Roy has depicted Gandhi performing apparently mundane activities – relaxing on a sofa, wearing headphones, steering a trolley stacked with groceries and riding a motorcycle, to name a few. The objective, in Roy’s words, is to “humanise someone who loved humanity”. But Roy’s dexterity achieves far more than that.

Roy makes Gandhi a figure of bathos, someone who has relinquished the responsibility of being the Father of the Nation and is interested merely in getting on with life. Unlike the political regimes that have helmed India, Roy does not see Gandhi as a vessel whose breadth can accommodate any worldview or ideology so as to serve narrow political interests. Instead, he visualises Gandhi as a toy, mostly devoid of promise and purpose, existing for his own sake and evoking some wry humour in the process. Mostly, but not entirely.

Some of the Gandhi likenesses conceived by Roy do have a purpose, if not necessarily a promise. The purpose is to critique the present political climate in India where the appropriation of Gandhi feels hollower than it has in the past.

Roy uses three figurines of Gandhi to reference the Swachh Bharat campaign (Gandhi is shown with a broom in hand), the chowkidar trope that gained traction during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections (Gandhi is shown with a stick in hand), and the politics of the cow (Gandhi is shown with a smart tablet in hand, possibly clicking a selfie with a cow). The brazenness with which the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its underlings have repurposed Gandhi is clear without being spelt out.

Photo courtesy: Akar Prakar and the artist Debanjan Roy

“The BJP need Gandhi to project themselves in a noble light in front of the world. They don’t really have any other historical figure to count on,” quips Roy. In the same breath, Roy acknowledges that this “need” has made the Gandhian legacy more toxic since 2014, not least because of the “polarisation and jingoism that the BJP has provoked”.

This is not to say that Gandhi has now become a byword for majoritarian nationalism. It is to say that by resorting to Gandhi every now and then, the BJP have blurred the distinction between the India that Gandhi pictured and the India that is taking shape today. Gandhi’s Ram Rajya has not yet been invoked as the theoretical precursor to the Hindu rashtra, but the signs of an ontological allyship are certainly being manufactured.

Roy, who has wanted to be an artist since his childhood, is a natural carver. This is evident not only in the seamlessness with which he has designed Gandhi in so many avatars but also in the hints he has inserted into each of his carvings. A close look at the eyes (wherever present) and the mouths of the various sculptures betrays the nimbleness of Roy’s imagination.

Photo courtesy: Akar Prakar and the artist Debanjan Roy

Gandhi as Superman wears his cape like a burden, while Gandhi with the aforementioned stick in hand has a faintly menacing air about him. On the other hand, the Gandhi who is navigating his way around a supermarket while conversing on the phone is content and cheerful, perhaps converted at last by market forces and a free mobile connection to endorse the banal benefits of everyday capitalism.

The stretch marks on a few of Gandhi’s faces suggest resignation, a Frostian internal sighing that can stem, equally plausibly, from regret or relief at all the roads not taken. The decision to get rid of Gandhi’s eyes in a couple of models while retaining the famous spectacles is also characteristically open-ended from Roy. Is Roy trying to say that Gandhi’s vision has been hollowed out, and therefore, whoever controls his spectacles (and the spectacle around them) controls what Gandhi sees? Or is he insinuating that Gandhi’s spectacles have attained omniscience, so much so that his eyes have become redundant?

The answer proves elusive, even for Roy.

While talking about his exhibition, Roy has a tendency to digress, and spontaneously kickstart a parallel conversation, such as the time when he spends a good five minutes voicing his regard for The Mahabharata. But like all accomplished thinkers, Roy has a way of making his digressions count, of taking a thread or two from his detour and connecting it back to the main route.

“Do you know what is the greatest dharma?” Roy asks. “Well, Yudhishthir did. He knew it was non-violence. And so did one man aeons later.”

The fact that Roy thinks meditatively about the context and the characters that go into his creations introduces layers to his craft. At first glance, his art is deeply visceral, unpredictable, even outrageous. But on careful probing, it begins to seem cerebral, things begin to make sense.

Modern sculpture is often seen as a forked path: either one appeals to the heart like Pablo Picasso or appeals to the head like Marcel Duchamp. Roy, when faced with this dilemma, chose both.

“He has always got something new to say. He likes to be unconventional, to make others figure out what he is trying to do. It is such a pleasure to collaborate with him,” says Siddhi Shailendra from Akar Prakar. She goes on to add, “This particular exhibition on Gandhi has received an extremely positive response. Visitors have been hooked. I feel that something like this is extremely relevant given the times we live in, it has a lot to say about the India we inhabit right now. This is why we opted to start this exhibition a day before Independence Day.” The exhibition ends on September 15.

Speaking of the India we inhabit right now, Roy is concerned, maybe even cynical: “Everything is about big business nowadays, a few people pulling the strings. And the cleverest businessman of them all is Narendra Modi.”

Eventually, like all impactful artists, Roy sees himself as a catalyst, not as a changemaker. His sculptures of Gandhi are aimed at those who have lapsed into complacency, accepting every wrong as part of the natural order. “The reason why we have BJP in power is because educated Indians have chosen to be ignorant. We have forgotten that we have a right to ask questions, a right to participate in the democratic process over and above the act of voting,” explains Roy.

After championing open-endedness and the absence of binaries throughout the conversation, Roy ends with what can only be described as an artist’s ultimatum.

Having paused for a few seconds to collect his thoughts, Roy speaks, with the assumption that the whole of India is listening: “All this time we have shown that we do not understand what we need. But it’s time to choose… We have to decide whether, as a nation, we need another Mohandas Gandhi or another Narendra Modi.”

Priyam Marik is a post-graduate student of journalism at the University of Sussex, United Kingdom.

This article was first published on LiveWire.

This article went live on September eleventh, two thousand twenty one, at zero minutes past seven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.