Art in the Time of COVID-19: Mirroring Brokenness and Hope

Among the many things that disappeared from our lives during the pandemic-induced lockdown was the pleasure of visiting exhibitions, attending concerts and going to the theatre – occasions that give us moments of aesthetic joy but also of reassuring sociality. Although exhibitions, like other cultural events, went online, making access from great distances possible, it took away the impact of engaging with artworks in a physical space, where each piece vies for attention only to come together to give voice to a compelling narrative

The heartening news is that after more than eight months, many galleries are opening their spaces to the public in a guarded way, with carefully curated shows, and oftentimes with an online version. This not only enables frequent virtual visits possible; it also encourages revisits across time and space. And, as one stepped into Kolkata’s Emami Art gallery recently to view the exhibition ‘Fluid Boundaries’ – it can still be viewed on Emami Art’s website – the sense of anticipation was palpable. One was eager to see the concerns reflected in the works of five young artists from Kolkata, put together by art critic and curator Nanak Ganguly. After all, it was a show of art in the time of COVID-19.

In many ways, what one saw was a testament to our times, where questions about mortality permeate mundane discussions and the anxieties of isolation are only just becoming more bearable from behind masks. The state of prolonged uncertainty and a break from routine appears to have prompted the artists to reflect deeply on issues that matter to them. In this unique state of fluidity, anchored by shared concerns, such as for the environment, the large and imposing artworks speak their mind without inhibition – with the themes of hope and despair, nature and human construction/activity, convergences and contradictions dealt with differently by each of the five artists.

Take Bholanath Rudra, whose huge watercolours, executed with remarkable mastery over the medium, respond to the daunting realities of the Anthropocene. 'Plantation', 'Press Conference' and 'You're under CCTV Surveillance' are works that revolve around the theme of the denudation and exploitation of Earth’s resources as a result of the relentless desire for ‘development’.

In the 27 feet long and almost eight feet tall dystopian sweep of 'Plantation', we come across a group of pack-mules pulling a six-axle cart, with two of them plodding along in industrial gumboots. A similar instance can be noticed in 'Press Conference', where a bevy of cameras are focused on a fox disappearing into a hole as the last tree burns to the ground, sending clouds of smoke.

‘Press Conference’ (2020) by Bholanath Rudra; watercolour on paper, 58.60 X 72.00 inches

A detail of ‘Press Conference’ (2020) by Bholanath Rudra

It is not the broadcasting cameras or the smoke signals but the single shoe on the fox’s hind leg that strings the narrative together. In the artist’s apocalyptic vision, the idea of development stands exposed as a porous concept that cannot keep humanity secure. Moreover, as Rudra sees it, if humanity continues to be blinded by the seductive lure of development, its fate is clear – man, who sees himself as the master of the universe, as a thinking being and caring cohabitant, will be reduced to the status of a pack-mule, the industrial gumboot a metaphor for enslavement.

The presence of the purveyors of greed is marked by the ubiquitous panoptic gaze of the CCTV camera. Seen from this vantage point, 'You're Under CCTV Surveillance' exposes how even at the top of the pyramid of plunder, the so-called winner is but a pack-mule, sans dignity, with no right to privacy – dehumanised.

However, it is interesting to note that there are instances in Rudra’s works where small acts of protests are registered. For instance, in 'Plantation' we notice a dog – proverbially loyal to the master – urinating nonchalantly at the base of a CCTV post, and we also witness how a single mule that dares to walk in the opposite direction, starts to grow a human foot.

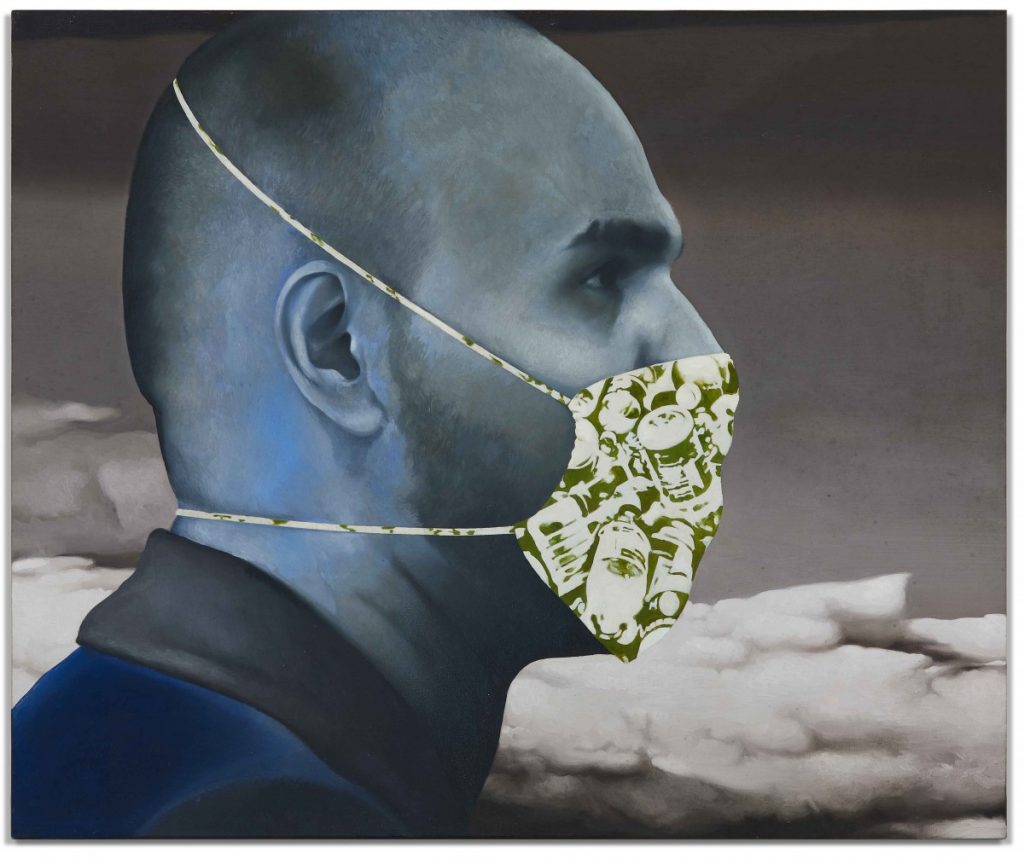

The only artist in the group who has lavishly populated his canvas with human beings is Snahasis Maity. In his photo-realistic depictions, people are mostly lost in dreams, their sagging shoulders depicting their submission to fate as they stare into the abyss. Maity’s 'In between' reminds us of Nietzsche’s famous quote, if you stare into the abyss, the abyss stares back.

‘In between’ (2018) Snehashish Maity; oil on canvas, 40 X 48 inches

The man in the painting is not only staring at the unpleasant realities of the pandemic but is also enervated by it. If in Rudra’s paintings all men are unwittingly complicit in the machinations of those ensconced in the seats of power, then here, unhinged from reality, they are transposed into an unreal space of inaction. Displaced and disheartened at home and in the world, dreams seem to be their only refuge.

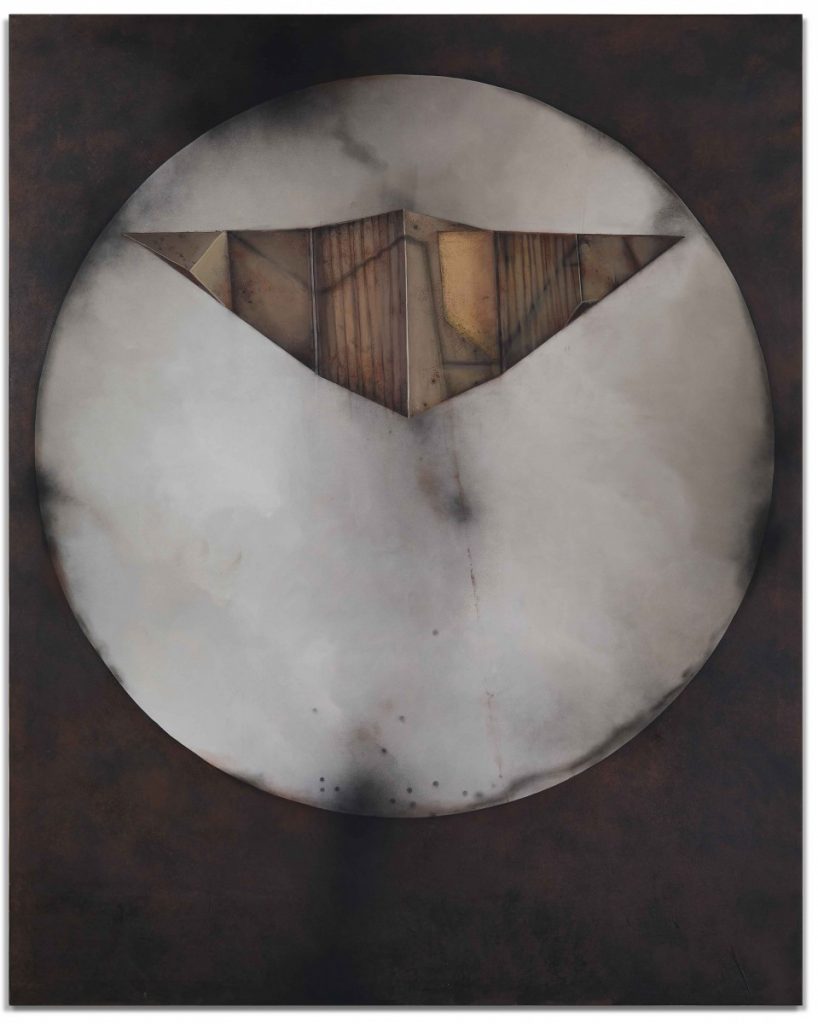

In the paintings of Suman Dey, the most abstract of the lot, the message seems straightforward, in keeping with the artist's palette and consistent with his conceptual explorations. Dilapidated corrugated metal sheets patched and put together in a shape resembling airplanes (a metaphor for the fallen man?) negotiate space and creative possibilities as they test the resilience of abstraction faced with the challenges of our time.

If the titles and visual contents of the works such as 'Journey III', 'Space and Possibility' and 'At the End' are any indication of the trajectory of his thoughts, then Dey’s verdict seems rather sombre. At the end of the journey, the flight of hope seems to have crashed and reached an impasse.

‘Space and Possibility’ (2020) by Suman Dey; acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 72 X 90 inches

The other artists in the show, Tapas Biswas and Debasish Barui, stand out not only because they work with sculptural forms, but because they appear to be searching for the middle ground, where opposing forces of nature and human endeavour could co-exist.

Biswas has spoken of his fascination with colonial architecture and its floral motifs. This interest seems to have left a mark on his work. For instance, his Flower becomes Fossilised shows a giant flower made of coiling copper. The curves and curls, twist and turns of the sculpture mimics—both in appearance and essence—molten lava that is neither totally dead, nor completely alive. The idea of the flower motif, probably plucked by the artist from some Corinthian pillar in Kolkata while on an evening stroll, is 'fossilised’, but the flower continues to burst forth into existence in swirling motion.

‘Flower becomes fossilised’ (2018) by Tapas Biswas; copper, 54 X 56 X 42 inches

Biswas’s other works—Abandoned, Present Invites Future, and Varanasi—also deal with different aspects of life re-crafted in iron, bronze, wood and brass. It is interesting to note how in Flower becomes Fossilized and Abandoned, copper and iron have been used to mimic the vitality of a flower or the colour and texture of a mud daubers' nest. It is in Varanasi that the difference between architecture and nature totally collapses. Imposing buildings, steps leading up to the river Ganga, the densely populated ghat, come to form as a living and breathing landscape.

While in Maity’s works the man-made world is a source of anxiety, Biswas’s sculptures show us the possibility of a convergence, where man and man-made entities also become a part of nature.

Debasish Barui's Schizophrenia, Material and Desire, a kinetic installation consisting of miniature chairs arranged around a red throne on what appears to be a sloping parliamentary floor, swamped in a pool of burnt oil, shows us another dimension of human reality. Behind the throne as levers turn, unique yet nebulous shapes take random forms through a discarded motorcycle chain, denoting the utter futility of the system that has taken centre stage.

As elected representatives inch closer to the seat of power, beckoned by greed and ambition, they seem to be drowning deeper into the dark murky waters.

In highlighting human hubris Barui seems to concur with Rudra and Maity—the more pronounced critics of human frailty. But Barui seems to be more accommodative. This optimism is more clearly visible in his other kinetic installation, An Unaccustomed Earth. It is about those fissures, or cracks that live and breathe, that are found on human bodies and are better known to us as wounds—a mark of life, experience and endurance. So, the slab of soil pulsating in a dark room is the earth breathing and heaving, but not totally dead.

With the aid of motorised motion, Barui literally anthropomorphises the land – the impression of a wounded planet is communicated much more effectively than scientists can ever hope to do with their charts and statistics to show a world alienated from its roots in its surge for the so-called heights of development.

It is interesting to note how artists like Rudra and Barui have similar concerns but very different ways of expressing them. While Rudra chooses to literally dehumanise his terrain, Barui prefers to anthropomorphise his landscape to drive home the same concerns about nature. They work their way from two ends of the same spectrum.

'An Unaccustomed Earth' is about the meditative intimacy that helps us appreciate the ground that holds and sustains us. It is at once about remembering the wounds and the process of healing; it is about celebrating life while acknowledging the reality of death – a feeling that a crisis like COVID19 makes more palpable and relatable. The despondency of death and the hope of recovery share a fluid boundary in the installation under a bright light.

While the wounds inflicted on nature are mourned by the artists, in the exhibition’s overall narrative there is an attempt to keep the door open, as it were, to reflect on the prospect of healing – when human and nature are in sync. In that sense, the works of the five young artists give a tactile sense both of the brokenness that people feel at a personal and collective level and of the hope – more a prayer – of a revision that is actually a healing re-vision for the future.

Siddharth Sivakumar has studied English literature and writes regularly on visual art and culture for print and online publications.

This article went live on January twentieth, two thousand twenty one, at zero minutes past four in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.