Full Text | Drawing a Line: An Evening With Joe Sacco

Cartoonist Joe Sacco was hosted by The Wire on November 11, 2024 under Nehru Dialogues at Jawahar Bhawan in New Delhi.

In a conversation with Sacco, The Wire's Editor, Seema Chishti, spoke to him about his craft, experiences, the travesty of what is unfolding in Palestine, the significance of his books and the reason why 'objective' or so-called 'neutral journalism' does not work.

The following is a transcript of the interview, edited lightly for style and clarity.

§

Seema: A very good evening and a very warm welcome, Joe. Welcome to Jawahar Bhavan, Nehru Dialogues and to The Wire. And we're truly delighted to have this opportunity to speak to you and pick your brains. I think plenty has been said, and all of us here have been watching your work for years for decades, so you truly do not need an introduction to this room.

I just want to thank you for helping us be the lens through which we've been able to witness our times. You've allowed us to bear witness to horror that unfolds around us now and which has happened in the past.

You probably would have answered this question several times. You do comics journalism, you're a cartoonist, a war reporter, an author and you're a writer. So how do you describe your own work if woken up at 3 a.m. in the morning and asked to do so?

Joe: Well, first I'll get pissed off that someone woke me up at 3 am By the way, thank you for the introductions and I appreciate being here. I describe myself as a cartoonist. And part of the reason I do that is, I kind of got into the profession, if you want to call it that, to make people laugh. That's the reason I wanted to do comics. And over time, the comics became obviously more serious and took on a journalistic aspect.

But I prefer the word cartoonist because I've always wanted to delve into something other than journalism. It might not be reflected in most of my work, but I need to keep that elbow room. But if I had to describe what most of my work is, it is comics journalism.

Seema: You have a degree in journalism and then you have this amazing talent. So these two things, the artistic and the journalistic impulse, which sometimes needs much coarser ways of documenting the time. How do you bridge the two things? And why did you think of melding the two together? Would it simply be easier to write or photograph or to do video?

Joe: Well, I did get a degree in journalism and I wanted to be a news writer for a newspaper, but I could never find a job doing that. And to make a long story short, after two or three years of sort of soul-crushing semi-journalistic jobs, I just decided to get out of it and fall back on something I'd been doing as a kid, which was cartooning.

At some point, I ended up in Berlin doing rock posters and album covers.. But I was still very interested in the world, that's why I got involved in journalism. And I was particularly interested in what was going on in the Middle East and with the Palestinians.

I decided that I would do a series of comics about traveling there. So I initially thought of it as a travelogue. While I was there, it turned into more of a journalistic project because journalism was in my blood in a way.

So without really thinking about it too much, I began asking questions like a journalist, behaving like a journalist. And so the two things, my artistic side and the journalistic side, came together but there was no theory behind it. I didn't sit back beforehand and say, this is what I'm gonna do.

I just went and things very organically developed. Later on, I became more self-conscious. And part of the reason I become self-conscious is because people ask me questions and then I do have to theorise.

Seema: What does taking notes mean for you? Do you take pictures, rough outlines or sketch as you speak?

Joe: I mean, if you saw me in the field, I wouldn't look much different from an ordinary journalist. I'd be taking notes and I would be recording conversations and I take photographs for reference. What I tend not to do is sketch.

I only sketch if it's a situation where it might be a bit dangerous to take a picture. You're told not to take a picture, but you're not told you can't draw something. So that's what I do.

I tend to take the photographs because I want them for reference. And prefer to speak to people and spend my time in that manner. But when I'm asking questions, I'm asking visual questions of people. It's not just the typical questions, it's also questions that will help give me a picture of what a scene looked like.

Seema: You also draw yourself in the pictures. Could you take us through the process of drawing yourself into it? Because journalists make so much about keeping themselves out of the story, conversely also pushing themselves too much into the story. But how does Joe, the illustrator, cartoonist, jump into the panels?

Joe: Well, again, that was something that sort of developed accidentally without too much thinking about it.

At that time, I came out of a North American tradition of doing autobiographical comics. So when I went to the Middle East and the Palestinian territories without understanding what I was doing in a sense, it just seemed this was carrying over my autobiographical work. So it would be my experiences in Gaza or in the West Bank.

Over time, I realised the journalistic advantages of it, especially that having my figure in the panels sort of signals the reader that you're seeing this through the eyes of one journalist.

Also read: ‘The Gold Standard American Journalism I Was Taught Had Pulled Wool Over My Eyes’: Joe Sacco on Gaza

I'm not some demigod authority about a subject. I'm a living, breathing human being who is interacting with people and is subject to the forces of conversations and the things that are going on around you. And I want people to understand sort of the seams of journalism, the seams of getting things done in contexts like that. Because to me, it was always mystifying, even when I was studying it.

The other thing it made me realise is that I don't really believe what I was taught about objective style journalism. I sort of jettisoned that. And having my figure in the comic books suggests that. This is a subjective experience that's happening here.

Seema: A little more on subjective, what you say about objective or so-called neutral, which is even a worse word than objective. But there is what's also called balance in journalism about both sides and doing some kind of arithmetic mean and that's where the truth will lie.

So what are the dangers with that conception of journalism today that we see a lot of? Some of the worst journalism is being held up as correct and accurate because it's balanced and it gets both-sides.

Joe: Well, I mean, this almost speaks to what the introductions were about, about the Palestinians. I grew up thinking Palestinians were terrorists. That wasn't because I was studying the issue or I had a dog in that fight.

It was sort of through osmosis, without paying particular attention to the issue. When I was in high school, what I was hearing on TV, what I was reading in the newspapers, every time the word Palestinian was mentioned, it was also in conjunction with the word terrorism. So it was: Palestinians have hijacked a bus, the Palestinians have hijacked a plane, the Palestinians are firing rockets.

All these are objectively true facts, but the other objectively true facts were never really filled in. You didn't find out what Israel was doing and you certainly didn't understand the history of why things were happening the way they were happening. You never got the context.

In the early 80s, when Israel invaded Lebanon, their army moved up to Beirut. And in one incident, they surrounded a Palestinian refugee camp, Sabra and Shatila, and their Lebanese allies, Christian allies, went into the camp and killed hundreds and hundreds

of Palestinian civilians in cold blood. And I remember seeing the photographs in Time Magazine and thinking ‘but I thought the Palestinians were the terrorists’.

So something just snapped a bit. And of course I was upset by that, but I already had a degree in journalism. And I thought, well, the gold standard American journalism that I was taught actually pulled the wool over my eyes.

Also read: Day 449 in Gaza: Two Poems

And a resentment developed that I was led into this pit of misinformation. And I made it my task to learn about it and to find out what Palestinians had to say.

I never really feel that I have to balance this with an Israeli point of view, because the truth of the matter is, especially if you grow up in the West, the Israeli point of view is all you hear. It's always a battle of narratives.

And in fact, in those days, there was not even a Palestinian narrative from an American point of view.

Seema: So conflict seems to have kind of attracted you. You have a very wide oeuvre, but conflict kind of drew you from the very start. Was that because of your time in Malta? And I think you've also sketched something on your mother's reminiscences and her recollections of the Second World War. So tell us a bit about that.

Joe: Well, I grew up in Australia, really. I was born in Malta, but I was a baby when we left for Australia.

And Australia was full of people who had immigrated from Europe after the Second World War. And so the talk of people of my parents' age was about the war. When people came over from Poland, Germany, Ukraine or wherever it was, you heard stories of the war.

And my parents had certainly endured a lot in the war. Malta was, at that point, the most heavily bombed place on earth. It was a small island, a British base. And the Germans and the Italians bombed it for two-and-a-half years, and it was under starvation conditions.

I heard a lot of those things. And the idea that war can be present in your life was never really far from my mind. It made me interested, especially, in how civilians react in those conditions.

And one of my early comics, as you mentioned, was about my mother's experiences in the war. And she was a young girl, 14, who got a scholarship to go to the city of Valletta from her village. And the war was going on. And if she didn't go, she would lose her scholarship. So no matter what happened on the way, including being attacked by a German fighter plane, she never told her mother because her mother would hold her back. Those kinds of stories are what I grew up with. And I developed some feeling for what people have to endure.

Seema: You speak of how a very important part of your work is to speak to people and your illustrations give faces to real people. And I think it was Chris Hedges with whom you did some work where you spoke of how the people of Palestine themselves were not that interested in the 1956 massacres in Rafa and Khan Yunus. So tell us about when you spoke to the people there and they wanted you to concentrate on the here and now.

Joe: Yeah, I did a book called Footnotes on Gaza about 1956 and the massacres in Khan Yunus and Rafa. And my idea was to go and speak to older people about what happened in 1956.

Often in these situations, their sons and their grandsons are sitting in on the conversations. And sometimes the younger people would look at me and say, why are you talking about this historical event? Can't you see what's happening 200 meters from here? The Israeli army is bulldozing houses in rows. I understood why they were saying those things.

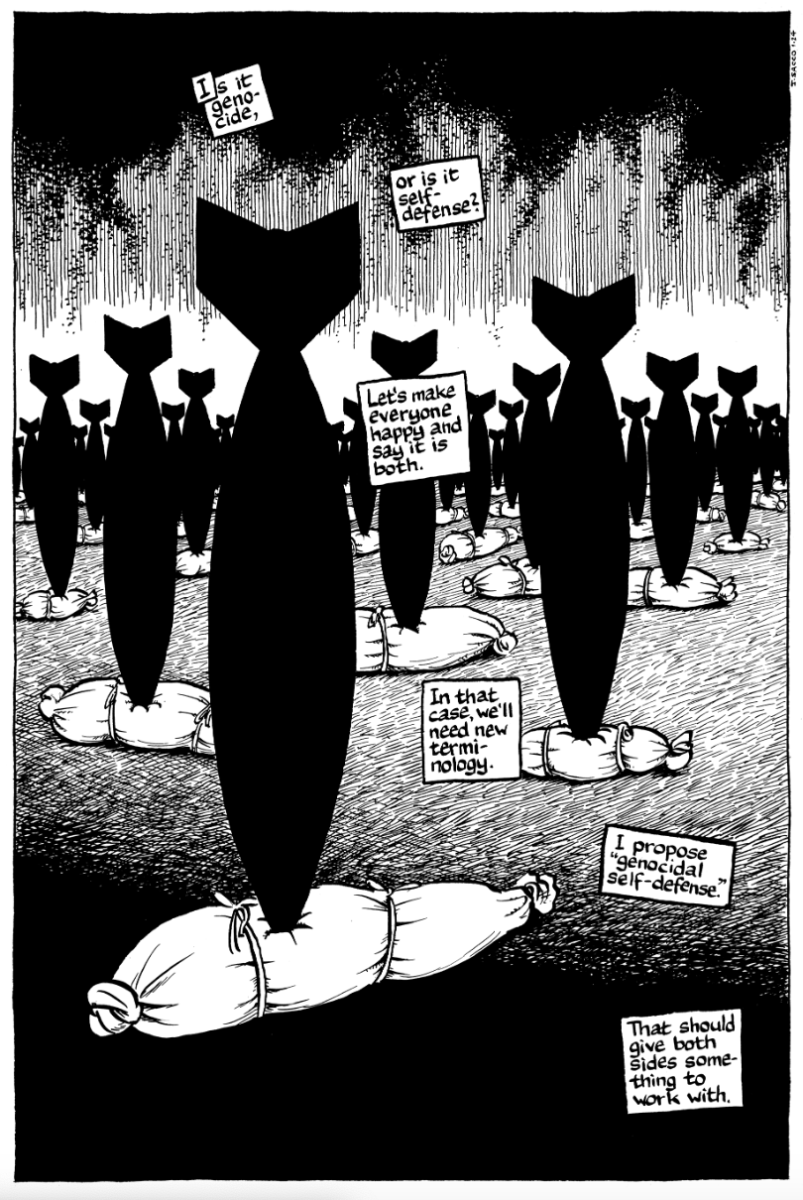

A panel from 'The War in Gaza'. Photo: Joe Sacco/The Comics Journal.

But what it shows to me in a way is that, as someone once told me, events are continuous. It's not like this event happened in ‘56. And that's something everyone can sort of digest and reflect on.

There is no time for Palestinians to digest a thing because something always is coming at them. So why would they talk about 1956? It might seem strange to them. Why would they talk about ‘56 now? But I can tell you why.

Because Chris Hedges and I met a guy named Al-Rantisi who was one of the founders of Hamas. And his uncle, when Al-Rantisi was eight years old, was taken out by Israeli soldiers, he was lined up against a wall and shot. And Al-Rantisi said, ‘at that moment, hatred entered our hearts’.

So that's why history is important. If you want to understand the context.

Seema: I just want to talk about something that Vignesh mentioned as we come to discuss some of the bearing of Gaza on today and the world outside Gaza.

And he said that how you had said that, ‘okay, it's a genocide and it's self-defence. So let's call it genocidal self-defence’. But do you think there's a reconciliation possible in the way the whole information world works on these two completely diverse world-views on self defence and genocide?

Joe: I don't think so. I think self-defence is something we understand. But if the term can mean anything from stopping someone at the border to coming and doing you harm to annihilating the whole people, then the term becomes kind of meaningless. I mean, if we're going to keep talking about self-defence, let's try to define what that means.

I'm not saying I have an answer for that, but I think it's a real mistake just to assume that everything can be covered under self-defence and that self-defence justifies everything and anything.

Seema: I think the latest number of the number of journalists killed in Gaza is about 137. So, of course, there is great destruction of children, whole people, women, young people etc. But just focusing for a minute on what has happened with the killing of journalists and people who will live to tell the story, what bearing does that have on journalists outside Gaza or the whole business of bearing witness and documenting things? Is this like a moment?

Joe: Well, I think any journalist who really cares about journalism understands that this is kind of a morbid and special moment. I don't think there's ever been a time when journalists have been targeted like this and have had to work under such horrifying conditions. It's not just about, I mean, journalists in war and there's personal safety issues, but it's different when you're targeted. And I think it's more different and even worse when your children, wives or husbands are targeted. That takes it into another realm. And my hat is off to those journalists who are sticking by it.

To them, journalism is a vocation. It's not just about sitting in front of a camera and reading something that's handed to them. I'm stunned by their bravery and their fortitude, but they should not have to, they shouldn't be going through that sort of thing.

Seema: So do you think it was easier to kill journalists in Gaza because they were Palestinians?

Joe: I think it seems to be possible to kill anyone if they're Palestinian. Journalists are a subset, but they're also killing medical personnel, people trying to clear rubble, people in safe zones. It really strikes me that this is happening. And of course, as journalists, we have to raise our voice about that.

We're getting into a world where certain things that seemed to be clear and are now no longer [clear]. It's like the rug is being pulled from under our feet. Everything is possible now.

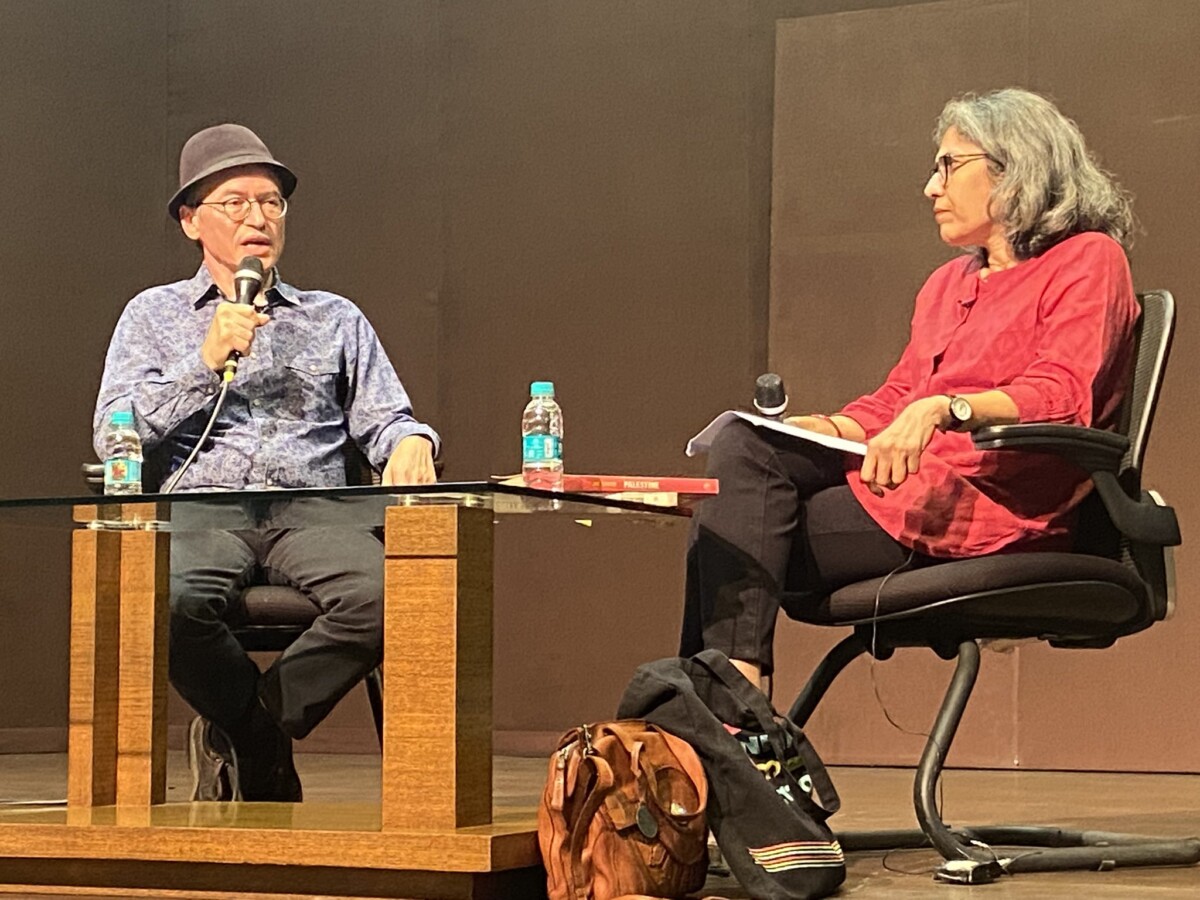

Joe Sacco in conversation with The Wire's Seema Chishti. Photo:

Siddharth Varadarajan/The Wire.

Seema: Is there any hope for the whole business of telling stories? And especially at a time when there is so much technology that threatens the whole idea of telling stories in a humane way and the politics in the world going the way it's gone.

Joe: Is there any hope? I'm not sure I would use the word hope. I think when you see the bravery of some of the people, you realise what humans are still capable of. And I hate to use the word inspiration because it's not inspirational. It's beyond the realms of what we're used to. But I see them working and it makes it, whatever troubles I might have with my work, whatever thumb might come down on any one of us, it's nothing like that.

Seema: At a time like this – when Trump has launched Truth Social, the richest man in the world is running X, and a flood of disinformation is circulating – where do you see the business of truth-telling, speaking out, and documenting our times heading?

Joe: Well, there's certainly a great amount of misinformation at this point. I can talk about the West, it's hard for me to talk about the Indian context, but in the West, the mainstream seems to have really discredited itself. It's bought into so many things. It's told us so many lies. You're seeing this especially with the story of what's going on in Gaza and the Middle East.

I think we're heading in that direction now, where it's really up to individuals who think of journalism as something that's as if you're a Jesuit priest. It's a vocation, it's a calling, you have to think of it in those terms. And with the amount of misinformation, we're gonna be swamped by it. That's just the way it is. But we have to keep the idea of what real journalism is, we have to try to get as close to the truth as we can, whatever problems that entails. There are those amongst us who just have to keep doing that despite the consequences.

Seema: I think relatively few people know about your visits and your detailed stories from Kushinagar and Uttar Pradesh and I think you were also working on a communal riot in India. I don't know if that book got out. But tell us something about what working in India feels like and when you were in Kushinagar in 2011.

Joe: It's out in France. If you can read French, you can order it. That was a very interesting story. It was about Dalits in Kushinagar and the schemes that are meant to help them and how those end up in reality.

The story in Uttar Pradesh, the book, is about Muzaffarnagar and the riot that took place there. So I went there about a year after the riots and I wanted to find out what people would tell themselves about what they did a year later.

So that's the basic thrust of that and as I was doing that, I realized there were other themes and one of them must seem obvious to you in India, but it's become more obvious to us in the

West and particularly in America, is the role of violence in electoral politics. That's the other part of it. It's sort of an examination of that.

Seema But any idea when the English edition of this will be out?

Joe: Yeah, the wheels of production sometimes move slowly, but there'll be an English language edition about 10 months from now.

Seema: I just want to read from Edward Said's foreword to Joe Sacco's Palestine and it's truly striking because that's what Joe's work does. This may cause him embarrassment, but I'm going to read from here.

‘Nowhere does Sacco come closer to the existential lived reality of the average Palestinian than in his depiction of life in Gaza, the national inferno. The vacancy of time, the drabness, not to say, sordidness of everyday life in the refugee camps, the network of relief workers, bereaved mothers, unemployed young men, teachers, police, hangers-on, the ubiquitous tea or coffee circle, the sense of confinement, permanent muddiness and ugliness conveyed by the refugee camp, which is so iconic to the whole Palestinian experience, these are rendered with almost terrifying accuracy and paradoxically enough, gentleness at the same time.

Joe, the character, is there sympathetically to understand and to try to experience not only why Gaza is so representative a place in its hopelessly overcrowded and yet rootless spaces of Palestinian dispossession, but also to affirm that it is there and must somehow be accounted for in human terms in the narrative sequences with which any reader can identify.’

And I think coming from Edward Said, that's really rich praise and it's a long forward, so Said has taken his time.

This article went live on January second, two thousand twenty five, at thirteen minutes past five in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.