Introduction

The 1980s were a time when the women’s movement consolidated across India as groups protested and agitated on the streets to highlight the issue of ‘bride burning’ and ‘dowry death’. There was a concerted campaign for a change in the law. There were cases of young brides being set on fire by punitive in-laws for shortfalls in dowry; newly-wed brides committing suicide to save their parents any further suffering; and unmarried women taking their own lives to spare their parents the burden of providing a dowry for them.

The issue which was seen through the prism of ‘custom’ by large sections of society, found expression in bare, neutral, bland reportage in the newspapers, as suggested by daily headlines like – ‘Woman throws herself in well; drowns’. This was not new. Dancer-choreographer, poet and writer, Chandralekha, remembered similar headlines in the 1950s too when, as a young woman, she had snapped at her mentor, poet Harindranath Chattopadhyaya, exclaiming: ‘What does this news say? It says nothing. Nothing… Tell me, can poetry replace what news media takes away’?

Harindranath Chattopadhyaya and Chandralekha.

Harindranath’s response to Chandra’s indignation was instant. He wrote out a poem in Hindi which transcended the ‘black and white information’ in the news, to reach out to its ‘essence’ by amplifying the interior world of the woman trapped in her desperation. It was a statement of resistance rooted in artistic expression.

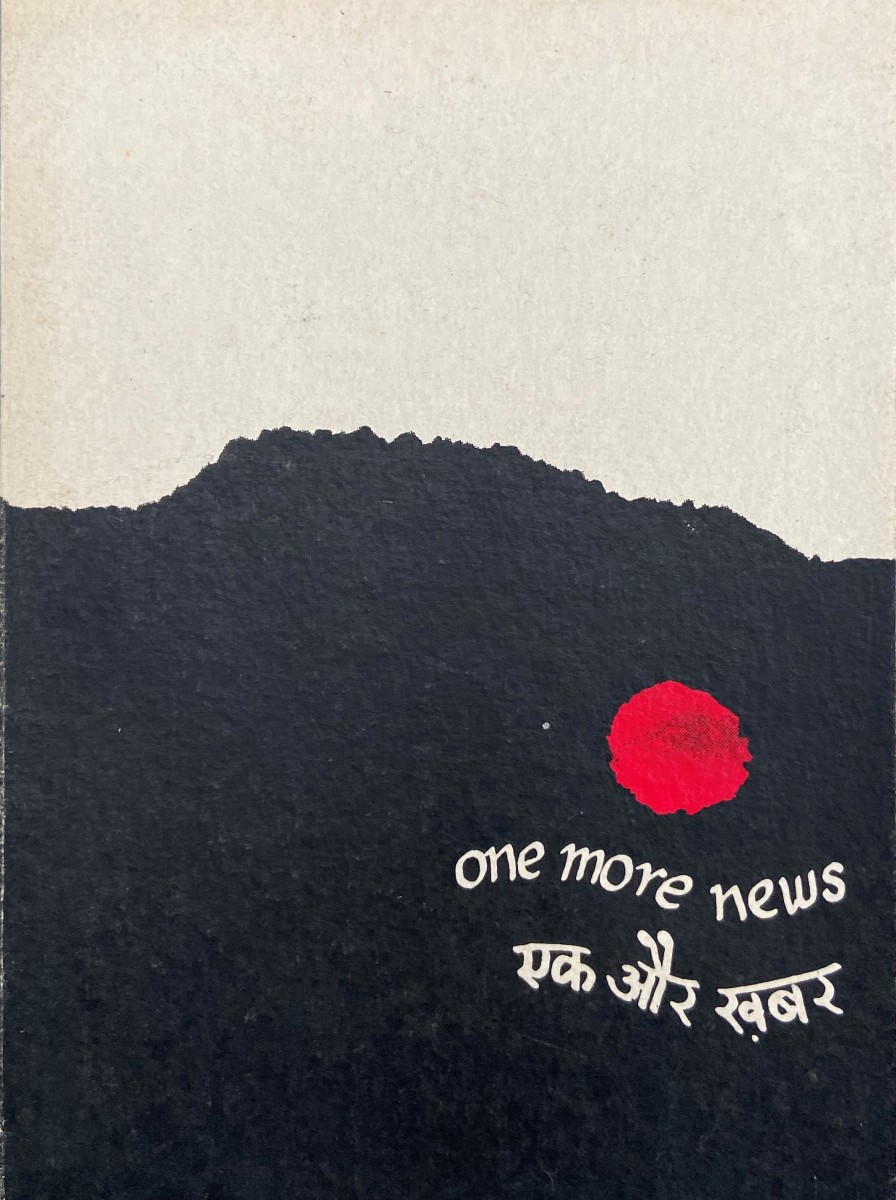

In the 1980s, at the height of women’s groups mobilising all over the country, Chandra remembered this evocative poem and was inspired, in turn, to paint miniature-style card paintings of tightly compressed images, that capture the utter loneliness of the woman in the face of a heartless State. The collage-like mixed-media visuals packed with stormy, accumulated energy, resounded like the echo of a silent scream. It took the shape of a book, titled Ek Aur Khabar or One More News (published by Skills, 1987).

The poem and drawings were presented at workshops across the country by women’s groups. They were recited, put to music, made into theatre. As Chandra put it: ‘Each media was explored to extend the impact of the content, to create and experience, to personalise involvement, to humanise the response.’

The poem and drawings were presented at workshops across the country by women’s groups. They were recited, put to music, made into theatre. As Chandra put it: ‘Each media was explored to extend the impact of the content, to create and experience, to personalise involvement, to humanise the response.’

We reproduce the Hindi poem in Devnagari as well as Roman script. It is followed by an ‘Afterword’ written by Chandralekha, a reflection breath-taking in its expanse and depth, with layers of association drawn from history, mythology and philosophy; an essay that communicates with the reader as urgently as it did when it was written.

Interestingly, she wrote the ‘Afterword’ even as she had begun to work on a collaborative project with the dramaturg Rustom Bharucha and director Manuel Lutgenhorst – ‘Request Concert’, a play by the German playwright Franz Xaver Kroetz, which is about a lonely, friendless woman pushed to end her own life. Significantly, in Chandralekha’s wordless interpretation (performed in 1988), she rejects the final option of suicide, to return from the brink.

Ek Aur Khabar

Neerav nabh mein purna chand ka

aghor ghanta baaje

Neeche nidrit ek kuen mein

nistabdhata biraje

Swapnaheen wah kuan khada hai

sudoor khet kinare

Aj ik naari nirjan path pe

bhatkat dukhan maare

Aaspaas khamoshi tooti

aasmaan hua andha

Aur achanak andher chchayee

doob gayo re chanda

Tooti neend kuen ki chchanbhar

chaunk utha ghan paani

Khatam hui hai ik dukhiya ki

kroor kathor kahani

Desh dayalu nahin hai naari

sachmuch zaalim thahra

Desh dayalu nahin hai naari

kewal andha bahra

नीरव नभ में पूर्ण चाँदका

अघोर घंटा बाजे

नीचे निद्रित एक कुवेंमे

निस्तब्धता बिराजे

स्वप्नहीन वह कुंवा खड़ा है

सुदूर खेत किनारे

अज इक नारी निर्जन पथपे

भटकत दुःखन मारे

आसपास ख़ामोशी टूटी

आसमान हुआ अँधा

और अचानक अंधेर छाई

डूब गयोरी चंदा

टूटी नींद कुवेंकी छनभर

चौंक उठा घन पानी

खतम हुई है इक दुःखियाकी

क्रूर कठोर कहानी

देश दयालु नहीं है नारी

सचमुच ज़ालिम ठहरा

देश दयालु नहीं है नारी

केवल अँधा बहरा

§

Afterword – A reflection by Chandralekha

I am not talking about women beaten, bruised, attacked, assaulted, strangled, burnt, hacked.

I am not talking about women finished off within the four walls where they had no say, no way to protect themselves from their killers – usually the so-called near and dear ones – where they were overpowered by brute strength or number, where they were paralysed and rendered powerless, where there was no knowing what awaited them that particular day, that particular moment, or perhaps they sensed and suspected the ominous danger only generally and could hardly believe in the reality, the actuality of it, nor could they visualise their own death, for when one is alive (and young), death does not exist; it is simply not real; it is simply not there.

It will be cruel and unfair to ask those women –

but why did you not fight

but why did you not run away

but why did you not hit back

but why did you not call out for help

The evidence is clear.

They will not answer.

They are taught not to question.

They are brought up that way. To serve and obey.

They have acquiesced to their role of subservience.

Chandralekha.

It is an agreement between two parties with them as silent partners. They are committed. They honour the code and abide by its conditions. It is sacrosanct.

Nor will they run away from their oppressors. Under the agreement, their assaulters are safe from them, even if they be puny.

They will yield, suffer, die, make an offering of themselves. Their timidity almost attracts their assaulters. Their sacrifice is at once a ritual, a precedent and an example.

They will not blame those who attacked them and who were cruel and ruthless in their killing. They will not sin by pointing a finger at them. They will not pollute their last moment by such a sin.

Who burnt you?

Who set fire to you?

They will not answer that question.

The finger is pointed towards their own forehead; their fate. Their religion and upbringing answers for them. It is a magical transference. From the concrete to the abstract. Everything is resolved at once.

The dying moment must be pure and free from sin. The dying statement a magnanimous act of purification and forgiving. They will redeem themselves by forgiving all – men and gods.

I am not talking about women killed brutally, done to death. I am talking about women who take their own life – what is loosely called suicide. We read about them in the daily newspapers, small insignificant news.

Woman throws herself in a well

Woman burns herself

Woman found hanging

Woman kills herself, kids

The news does not create space. It stops all thinking and feeling. It numbs the senses. It numbs the human will. The news doesn’t tell you anything except a number. A woman. One woman. It doesn’t tell you who the woman was. It doesn’t tell you what happened. It doesn’t tell you of her predicament, of how she came to that momentous decision. A decision to kill herself.

To kill oneself needs courage. A very high degree of courage. A special kind of courage. Who was that woman. What kind of courage did she have in her. Was she conscious of it. Did she know she had power. Power to kill – a power that can be put to use in equal measure against oneself or the other.

I have always marvelled at the infinite capacity of women to bear, to suffer pain. It is said giving birth is the greatest pain in the world. Women go through it, often silently, casually, as if it was one of those ordinary things. And the world would have them believe so.

Where do they get the strength to bear pain without anger, without protest. From where do they get courage. Do they know they have power. Power to create. Power to give birth. Power to create life. Do they have a subterranean link with the beginning of creation. Do they have memory of their fertility and of the time they were goddesses on earth sustaining land and people and sun and moon; when they dreamt and thought with their body and made the world manifest. From where do these women get the power to kill themselves. Is it, then the same source as their power to give birth.

To kill oneself and kill the other seem two contradictory activities. Both acts require the same kind of energy. Killing the other is often an act of mindlessness. Killing oneself needs mind, involvement, commitment. To take life and to make life, both require the same explosive energy.

Women depend on others for taking decisions about their life. From the time they are born. Even before. Pre-natal. Whether they should be allowed to be born or not, to breathe or not, to exist or not, is a decision taken by others.

Taking one’s life seems to be the one and only time a woman exercises her right of decision-making. It has a finality. There is no going back. It has a feel of liberation. A false feel of choice and alternative. To step out of one’s life, to make a break from one’s life would need super-human energy. In life as well as in death. It seems women give this energy freely and abundantly.

What they do not realise is that they give this energy to their oppressors; that their death instead of a protest and a statement of indignation is an acceptance, a submission, a contribution to the perpetuation of their oppression. It is a gift given gratis.

If women became aware that their dying will not change other women’s destinies but, on the other hand, will reinforce their oppression, will they not opt, instead of death, for life, however difficult, rough, harsh, cruel.

Would they not give their energy to change rather than to the maintenance of oppression, of status quo? Would they not give their energy to their sisters, rather than to their oppressors?