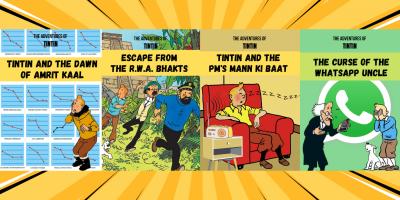

Satirised versions of the Adventures of Tintin comic book covers have been around for a long time. It is no surprise that a number of ‘India-friendly’ Tintin cover adaptations, too, have surfaced on social media recently.

For example, Tintin and the Dawn of Amrit Kaal shows the young comic book hero looking on in dismay at the statistics on the cover of Aakar Patel’s book, The Cost of the Modi Years. Escape from the R.W.A. Bhakts shows Tintin, Captain Haddock and Cuthbert Calculus fleeing, and Tintin and the PM’s Mann ki Baat shows him dozing off in front of a radio.

The Curse of the WhatsApp Uncle with Tintin holding his head while listening to an old man’s harangue is particularly funny.

While the artists of these versions are anonymous, around the time of the inauguration of the new parliament building in May 2023, another Tintin adaption, appeared on social media – King Savarkar’s Sceptre. This one was drawn by graphic artist Orijit Sen. The depiction of an easily recognisable man in RSS uniform swinging a sceptre around provided some comic relief around the much hyped and controversial Sengol.

‘King Savarkar’s Sceptre’. Illustration: Orijit Sen.

It is worth noting that the original Tintin comic, King Ottokar’s Sceptre, whose cover was spoofed was also written as an act of resistance against two despotic regimes – Hitler’s and Mussolini’s.

The original cover of Herge’s ‘King Ottokar’s Sceptre’. Photo: www.tintin.com

Born in the Belgian suburb of Etterbeek in 1907, Tintin’s creator, Georges Remi, (more popularly known by his pen name, Hergé) lived through both world wars. The Belgium that he grew up in was a hotbed of right-wing politics and fascism and the first couple of Tintin books unfortunately reflect the ethos of the day.

Tintin in the Land of the Soviets and Tintin in the Congo were shamelessly propagandist and racist, something Hergé remained embarrassed about till the end of his days. (Their creation, though, was directed in large part by Norbert Wallez, owner of the magazine Petit Vingtième that Hergé worked for and that the adventures of Tintin were first featured in. Wallez was a card carrying fascist and even kept a photo of Mussolini on his desk.)

But as the true nature and extent of European fascism began to reveal itself in the 1930s, Hergé decided to resist the Nazis through his art. The plot of King Ottokar’s Sceptre was, in fact, directly inspired by the ‘Anschluss’, Hitler’s annexation of Austria, which took place in March 1938. The mythical country of Borduria was quite recognisably representative of Nazi Germany, and the imaginary country of Syldavia represented not just Austria but other nations under threat from Nazism as well.

As Hergé’s biographer Harry Thompson explains:

“In the comic, King Muskar XIII of Syldavia is the target of the Iron Guard, a fifth column who plan to steal the ceremonial sceptre of Ottokar without which he is not permitted to rule. Thereafter, under the command of Müsstler, the Iron Guard leader, Bordurian forces plan to seize control of the Syldavian capital Klow, ostensibly in defence of Bordurian nationals – who will be beaten up on the day to provide a suitable excuse. The name Müsstler is, of course, a straightforward combination of Hitler and Mussolini.

“Hergé even dressed the Bordurian officers in SS-style uniforms… It says something about Nazi stupidity that they actually failed to spot the blatant attacks in King Ottokar’s Sceptre.”

Though ostensibly an adventure story for children, King Ottokar’s Sceptre was a sober warning from Hergé to his fellow Belgians about the dangers of fascism and expansionist Nazism. He continued to attack Nazi Germany in subtle and not-so-subtle ways through The Land of Black Gold and The Black Island as well.

Hergé poses in 1979 next to the bronze statue of Tintin and Snowy, made by the Belgian artist Nat Neujean. Photo: Studio Hergés/www.tintin.com

At the end of the war, however, Hergé found himself being accused of being a Nazi sympathiser and was even jailed for a night. This was because he had started drawing the adventures of Tintin in Le Soir after the magazine he had drawn for before had shut down. Even though Le Soir’s circulation was five times that of Petit Vingtième, unfortunately for Hergé, its management passed into Nazi hands.

Hergé had kept his head down during the years of Nazi occupation, and the apolitical nature of the next few Tintin books, The Crab With the Golden Claws, The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham’s Treasure reflected his chosen political ‘neutrality’ at the time.

To his credit though, when approached by the Nazis to become a Gestapo informant, Hergé refused. He also refused to become the official illustrator of the Belgian Fascist movement. But because he had worked with Le Soir during the war years, the accusation of being a Nazi collaborator dogged him the rest of his days.

Hergé died in 1983, leaving behind an incredible legacy as ‘the father of the modern European comic book’. Had he been around today, he would most certainly have smiled at the way his characters are continuing to fight fascists.

Rohit Kumar is an author and educator and can be reached at letsempathize@gmail.com.