Trump’s Trade War Will Disproportionately Hit Developing Nations

“American industry was reborn, destiny was reclaimed, and the day America started to become wealthy again.” These were the words of US President Donald Trump, who declared April 2 as "Liberation Day" for American firms and businesses – a strategic move, he claims, that will bolster a new era of American manufacturing jobs, capital investment in states and retaliate against unfair trade practices by both friendly and unfriendly nations alike.

While some may define this as a reckless trade war unleashed in an already volatile global economic order, Trump’s weaponisation of tariff regulations to reorient production, investment and distributive supply chains may reorient trade relations between many nations across regions.

Asia, for instance, could see a total realignment in its trade and economic relations. China, Japan and Korea and other countries with high exposure to the US are already realigning their economic interdependence and gradually decreasing their dependence on the American economy.

With respect to India, the newly imposed 26% duty on Indian exports is likely to disrupt global trade and adversely affect both Indian and American economies in the short to medium term. Markets in Asia are already tumbling since Trump’s announcement. Gold prices have surged to a record high, approaching $3,200/oz as investors rush to hedge against economic uncertainty.

A recent report estimated that if the US imposes a broad, country-level tariff of 25% on Indian imports, India's GDP could take a $31 billion hit. This figure may be much higher now given the indirect impact of tariffs on countries where American and Indian product supply chains are deeply interconnected. It will also cause prices of inputs and intermediate goods to rise which will add to the cost of production for affected sectors.

The most affected sectors by these tariffs in the Indo-American context are likely to be electronics, gems and jewellery which form the backbone of India's rapidly growing export economy. For instance, in the case of smartphones, India contributes around 10% of US imports making this sector particularly vulnerable.

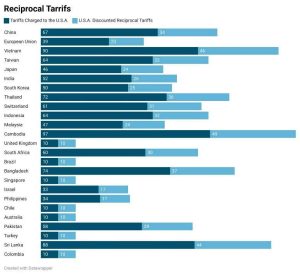

Source: The White House

While specific implementation details on sector and product-specific tariffs remain unclear from the announcement speech, the broader picture reveals Trump's unwavering commitment to protectionist policies including a baseline 25% tariff on all automobiles that will remain in place regardless of any potential exemptions granted to India.

This universal automotive tariff imposed by the US represents a fundamental shift in its trade policy that will reverberate throughout global markets regardless of diplomatic negotiations or concessions.

India's $9 billion labour-intensive textile sector will struggle against cheaper competitors like Vietnam and Bangladesh, risking millions of jobs. The $8.58 billion jewellery export industry will lose its price advantage to rivals such as China and Belgium.

Auto parts exports, valued at $2 billion, will face setbacks that will disrupt supply chains for US manufacturers. Even IT services, which send almost $100 billion in exports to the US, are at risk of retaliatory measures that could destabilise India's largest foreign exchange earner.

Source: Ministry of Commerce

Trump's imposition of 25% levies on steel, aluminium and other imports has had profound repercussions across global trade. While these policies were framed as efforts to revive American industries, they triggered retaliatory measures, disrupted global supply chains and reinforced a broader shift toward protectionism.

But beyond the economic uncertainties and geopolitical tensions, the greatest casualties of this trade war have been marginalised communities in developing economies, which now bear the brunt of trade restrictions imposed by the world's largest economy.

Disproportionate burdens on the vulnerable

Protectionist policies have exacerbated economic disparities worldwide, disproportionately affecting developing nations that rely on exports to larger markets. Countries like Bangladesh, Vietnam and Ethiopia, which depend heavily on textile, agricultural and manufacturing exports, now face additional trade barriers that restrict market access, stifling economic growth and employment opportunities.

Tariffs imposed on intermediary goods, such as machinery and electronic components, have also increased production costs, further discouraging industrial growth in these regions.

Canada and Mexico, two of the US’s largest trading partners, have also borne the brunt. Canada’s growth is projected to slow to just 0.7% in 2026, while Mexico, once forecasted to expand by 1.2% in 2025, is now expected to contract by 1.3%. Even the US itself has seen its economic outlook downgraded due to the unpredictable trade environment.

However, China, despite being targeted, has displayed resilience, strengthening its foothold in Latin America by deepening trade ties with nations like Brazil, Chile and Argentina. In 2022, China’s trade volume with Latin America reached $485.79 billion, exceeding $450 billion for the second consecutive year, highlighting the unintended consequences of US trade restrictions.

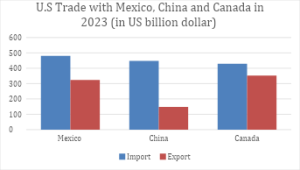

US Trade with Mexico, China and Canada. Source: UN Comtrade

Additionally, global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows declined by 12% in 2022 due to growing trade tensions, affecting developing economies that rely on investment for industrial expansion. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) noted that trade-reliant economies in Africa and Southeast Asia experienced a 20% reduction in export revenue during this period, leading to job losses and declining wages.

Collapse of food and medicine supply chains

Unsurprisingly, Trump's tariffs provoked swift retaliation from affected nations, with Canada, Mexico and China imposing countermeasures that hit US agricultural and industrial exports. The agricultural sector, a critical pillar of the American economy, has been particularly vulnerable.

Collectively, these three nations, accounting for over $80 billion in US farm exports, have imposed tariffs on American produce, exacerbating global food supply chain disruptions. US farmers, particularly those reliant on soybean, pork and dairy exports, have seen prices plummet due to lost market access, leading to increased government subsidies as a stopgap measure. In 2020 alone, US farm subsidies reached $46 billion, underscoring the cost of protectionism.

Also read: Global Reciprocal Tariff Exemptions to Pharma: Silver Lining for India?

Trade disruptions have also delayed the distribution of critical vaccines and treatments, worsening public health crises in regions already suffering from inadequate healthcare infrastructure. The global vaccine supply chain alone suffered a 20% cost increase due to supply chain disruptions between 2019 and 2022, placing additional strain on developing economies.

In addition, food price inflation exceeded overall inflation in 56% of the 168 countries due to trade disruptions.

The erosion of multilateralism

Beyond the economic disruptions, Trump’s tariffs have further weakened global trade institutions, particularly the World Trade Organization (WTO). Ironically, one of the WTO’s founding champions, the US has actively undermined its dispute resolution mechanisms, leaving smaller economies without a recourse against arbitrary protectionist measures.

The paralysis of the WTO’s appellate body means that marginalised nations, already at a disadvantage in global trade negotiations, are now even more vulnerable to economic coercion from larger powers. Since 2019, over 65 trade disputes have gone unresolved due to the WTO's dispute resolution crisis.

The erosion of multilateralism has also exacerbated climate injustices. Trade wars, by disrupting supply chains and increasing production costs, have made climate-friendly technologies and sustainable goods more expensive. This disproportionately affects developing nations already struggling with the consequences of climate change.

Tariff-induced inflation further compounds economic inequalities, driving up the cost of essential goods, from food to fuel, hitting lower-income communities the hardest. Meanwhile, countries with fragile economies and high import dependencies find themselves caught in an increasingly fragmented trade landscape, forced to pay higher costs for essential commodities.

Moreover, the trade war has had a tangible environmental impact. The shift away from cleaner imports in favor of domestic alternatives has placed additional environmental stress on vulnerable regions already experiencing climate-induced displacement.

The global order in disarray

Economic productivism, a set of policies that enable a rise in productivity and ‘good’ secured jobs if pursued through a renegotiated trade policy, has been part of the 21st century industrial policy imagination. To what extent Trump can achieve this in his second term is yet to be seen but there is precedence in having such radically pursued economic measures to one’s national advantage.

Former US President Ronald Reagon in the 1980s pursued similar trade tactics against Japan (in reducing automobile imports from Japan to America using quotas) at a time when Japan’s automobile cars were ruling the international market, which substantively allowed automobile investments by Japanese companies into the US, shaping the industry in the southern states.

Countries now also view trade disputes not as exceptions but as tools of statecraft and this shift may redefine trade agreements as temporary alliances, not binding economic frameworks. Both Trump and former US President Joe Biden have used tariffs to cater to domestic constituencies, proving how deeply embedded tariffs are in electoral strategies.

Trump viewed tariffs as a key component of his "America First" slogan and policy, specifically targeting the Rust Belt, where trade with China and globalisation had long been held responsible for the manufacturing collapse. Blue collar workers continued to support him because of his protectionist stance, disregarding evidence that retaliatory actions had adversely affected their economic well-being.

Despite being less confrontational in his speech, Biden upheld many of Trump's tariffs not because he believes they are effective, but rather because he recognises their electoral appeal. His advocacy of domestic industrial policy through the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act has demonstrated that protectionism is no longer limited to right-wing populism but is now woven into mainstream bipartisan politics. In an era of fractured alliances, tariffs have (unfortunately) become signals of trust, punishment, and alignment, tools not just of economics, but of power projection in a multipolar and multi-fragmented world order.

Despite Trump's promises, economic nationalism has neither made America great nor uplifted struggling communities. Instead, it has widened inequalities, destabilised global trade and pushed the world toward a more divided economic order – one where the marginalised suffer the most. The long-term ramifications of these policies will be felt most acutely by those with the least agency, making it crucial for global leaders to reassert their commitment to fair trade practices and multilateral cooperation.

While protectionist policies were initially justified to bolster domestic industries, their long-term impact has been a fragmented and exclusionary global economy. The dismantling of multilateral trade structures has reinforced economic nationalism, deepened inequality, and marginalised those with the least bargaining power in the international system.

Trump’s pro-business approach is less pro-market but seeks to prioritise short-term economic gains and popular mass voter for certain domestic industries at the cost of long-term global stability. His policies, riddled with contradictions, have triggered legal challenges from US states, backlash from international trade partners and mounting economic uncertainty. Unfortunately, as protectionism persists, the world's most vulnerable populations will continue to suffer the consequences of rising prices, deteriorating public services and widening economic divides as governments will respond to the US with conservative fiscal and monetary policies.

Deepanshu Mohan is a Professor of Economics, Dean, IDEAS, and Director, Centre for New Economics Studies. He is a Visiting Professor at London School of Economics and an Academic Visiting Fellow to AMES, University of Oxford.

The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.