In Photos: The History of Tourism in Kashmir

In 1956, the Jashn-e-Kashmir programme, initiated by Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad's government, sought to bring Kashmir into the national spotlight, particularly as a tourist destination. Over time, Bollywood films – from Kashmir Ki Kali, Junglee, and Bobby to more recent productions like Phantom, Rockstar, and many others – have been filmed in the region. Among these, Betaab remains particularly significant. The film was shot in the picturesque village of Hajan Wadi, near the site of a recent terrorist attack on tourists. The village was later renamed Betaab Valley in honour of the debut film of Sunny Deol and Amrita Singh.

Back then, Kashmir was known as a "Mini Switzerland." However, Sheikh Abdullah had advocated using the term “Switzerland” for a different reason: to signify the neutrality of the region, keeping it free from interference by both India and Pakistan.

A sniffer dog from the military checks vehicles coming from the LoC, including tourists. Photo: Shome Basu.

In 1963, Bollywood director Shakti Samanta proposed showcasing Kashmir as a romantic destination in his films – careful not to depict military installations.

But with militancy gripping the valley from 1988 onwards, tourism became a distant dream. Mani Ratnam’s film Roja, inspired by the real-life kidnapping of Indian Oil officer K. Doraiswamy, could not be filmed in Kashmir due to the volatile conditions.

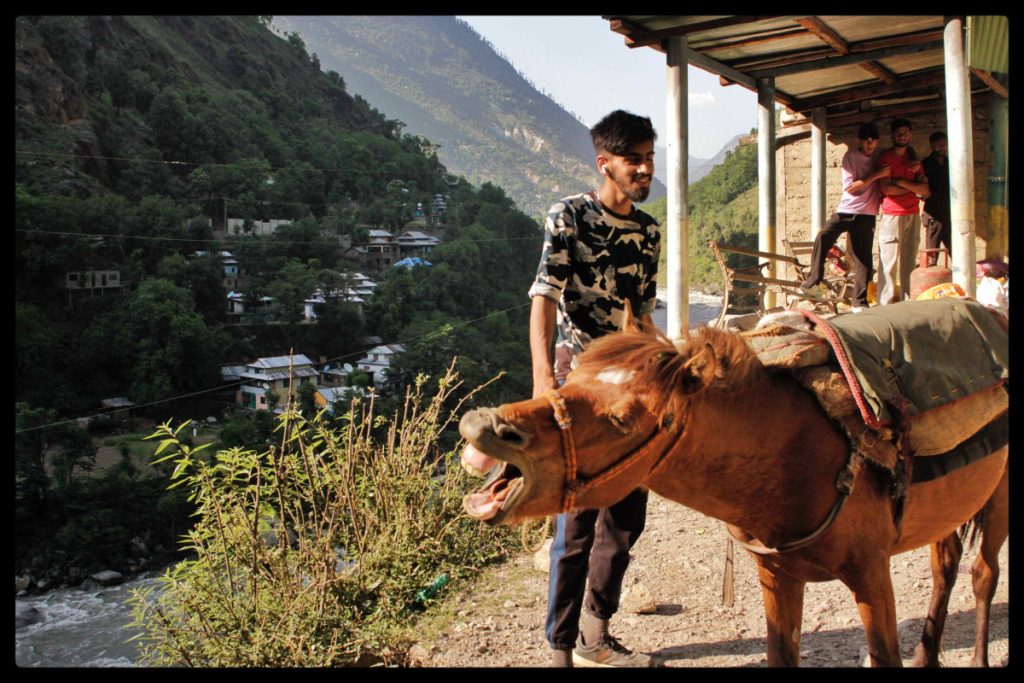

Pahari villagers ferrying ration to hilltops. Photo: Shome Basu.

Enter the idea of "Kashmir Obsession"—a term author Hafsa Kanjwal uses in her book Colonising Kashmir to critique how cinema and tourism have perpetuated an obsession with the place. While India asserts that Kashmir is an integral part of the nation (which it is), the political narrative often sidelines Kashmiris themselves. This disconnect has led to social and emotional estrangement between Kashmiris and sections of the Indian population.

The Line of Control (LoC) lies approximately 150-200 kilometres from Pahalgam.

An Army vehicle near the LoC. Photo: Shome Basu.

Tourists have long been pawns in terror strategies – kidnapped for ransom or leverage. Kim Housego was abducted in Pahalgam in 1994; it took 17 days of negotiations, led by his father and Indian intelligence, to secure his release. In 1995, six European tourists were kidnapped; one escaped, another was beheaded, and the rest vanished. The group responsible – Harkat-ul-Ansar – was led by Masood Azhar, then jailed in Tihar.

Since the reading down of Article 370 in August 5, 2019, it was claimed terrorism would be eradicated. That has not happened. Continued attacks – including the Pahalgam massacre – have exposed flaws in the much-vaunted security setup.

A statue honouring soldiers who laid down their lives along the LoC. Photo: Shome Basu.

Now, with the push for border tourism – taking visitors to Tangdhar, Tithwal, and Gurez near the Kishanganga River – tourists are even more exposed to geopolitical posturing. They risk becoming targets in a larger narrative.

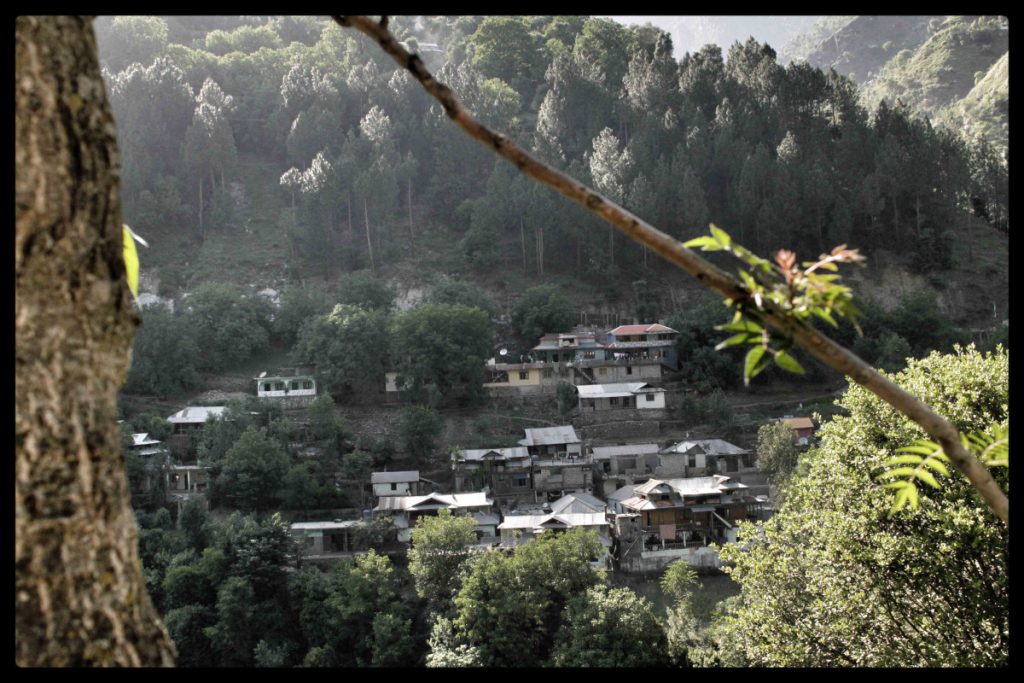

From one side of the river, villagers can see Pakistani flags, cars, and homes with electricity – while on the Indian side, many like Mohammad Ali, a porter, live without basic amenities. At his age, he and his wife still carry water uphill. His request was simple: “Set aside politics and think about our welfare.”

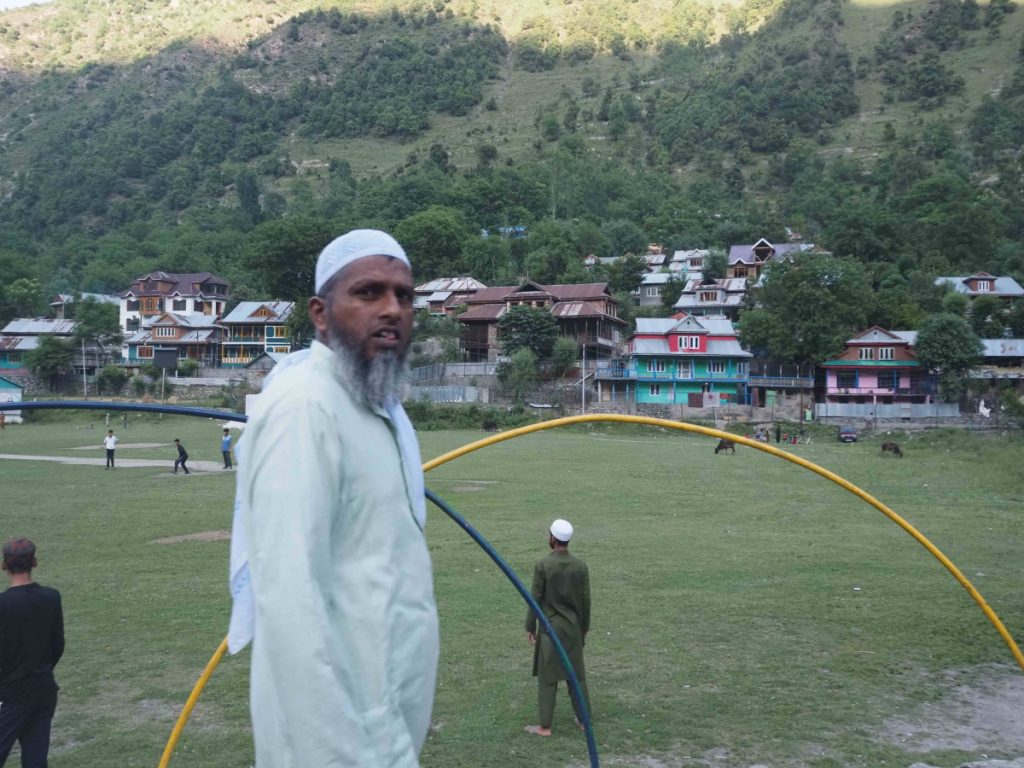

A man looks on as children play cricket in a village along LoC. Photo: Shome Basu.

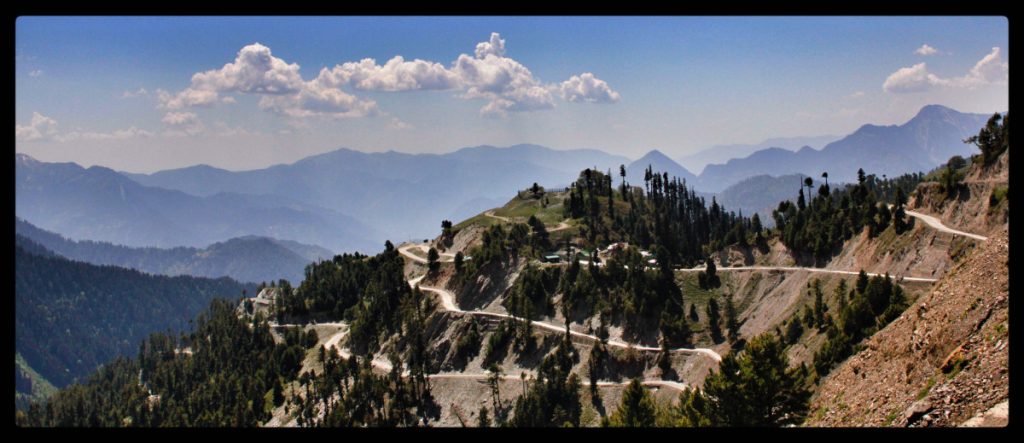

Permissions for such travel are relatively easy to obtain. Tourists pass through Uri, Bangus Valley, Kupwara, Tangdhar, and eventually reach Teetwal, near the LoC. There, the Indian Army screens vehicles, sometimes with sniffer dogs and stern questioning. Along the route lies the strategic Sadhna Pass. In the 1960s, while filming Arzoo, actress Sadhana was so taken by Nastachun Pass that it was renamed in her honour.

The Sadhana pass. Photo: Shome Basu.

Homes on the other side of Kishanganga along the Teetwal. Photo: Shome Basu.

Across the LoC in Muzaffarabad lies the Sharda Peeth, a revered Hindu temple. The Indian government built a replica in Teethwal, just meters from the LoC. Inaugurated by Amit Shah in March 2023, it quickly became a tourist attraction. Remarkably, the temple is now maintained by a committee including a local Muslim, Aijaz Khan, who works closely with the Indian Army. He explains that his effort is a response to the 1947 partition and conflict – an attempt to bridge divides through secularism and coexistence. Today, three Hindus, two Muslims, and a Sikh oversee the temple, an example of the syncretic harmony Kashmir once symbolised.

All photos by Shome Basu.

This article went live on April twenty-sixth, two thousand twenty five, at zero minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.