Extreme Weather, Fascinating Tribes and Grim Prisons: A Journey to Latin America's Patagonia

A couple clasp each other tightly and dance the tango on a sunlit street in Buenos Aires. They are dancing for tourist coins but it is startlingly sensual. It feels pleasurably X-rated for a busy street corner. Buenos Aires is the starting point for my long journey in South America through Patagonia.

It isn’t a country – Patagonia is a vast geographical region shared by Argentina and Chile, split by the Andes mountains. It’s a land with a near-mythical status for adventurers throughout history, a wild and untamed terrain battered by extreme weather. But its also known for some of the most sublime landscapes on earth – a mecca for photographers.

Colourful and sunny Buenos Aires. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

Dancing the Tango in Buenos Aires. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

Tourism to the region has increased, but it is still far enough off the beaten track to appeal strongly as a remote getaway. We will be trekking through some of the most iconic routes in Patagonia. The final destination is Ushuaia in Argentina at its southern-most tip. It’s Fin Del Mundo - the end of the world.

Buenos Aires is colourful, trendy and bustling. Money changers yell “Cambio, Cambio, Cambio” loudly at passers-by on the street. Greasy notes are exchanged for American dollars in dark, airless kiosks by a man with his money counting machine. It feels seedy and illegitimate, but it is a well-known part of the blue market – a fallout of Argentina’s flailing economy. Steaks and malbec are high on every tourist must-do list.

Plane views in Argentian Patagonia. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

We journey by bus and plane to El Chalten - the trekking capital of Argentina. The plane view of the icy mountains and crystal lakes are a prelude of what is to come. We travel hundreds of kilometres through vast and empty expanses, bleakly lovely but unwelcoming. The roads are very long and straight, there are only about two turns in five hours.

You rarely see another person or vehicle. Skeletons of dead guanacos – llama-like creatures – dot the landscape as they get trapped in wire fences. El Chalten is a strange, windblown little town, loomed over by Mount Fitzroy. It’s an odd mix of trekker hostels and rocker bars. I discover, much to my entertainment, that some workers live inside modified shipping containers – small, cosy and functional.

Vast and barren landscapes. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

You can’t be unfit to trek in Patagonia. We discover the euphemism behind the name ‘Patagonian Flat’. In reality, this is a steep walk with a few flat sections. The unpredictable weather is a theme for the whole trip. It is cold, wet and very windy - enough to make you fall over. There is an irritable saying here: "Don’t ask about the weather. It’s Patagonia".

Also read: An Experimental Eco-Tourist in Nagaland

En route to the base of Mount Fitzroy, the wind, rain and loose rocks have turned the walk into an ordeal. The sight of a glacier does little to lift our spirits on that dark and oppressive walk. Nothing seems worthwhile and when the rain comes in sideways, visibility is low and every step is squelchy misery. We climb on as the guide has held out the promise of a ‘shelter’ further on.

Walk to the base of Mount Fitzroy. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

We miserably imagine the dazzling luxury offered by this shelter. Visions of a fire and a warm drink rapidly evaporate when we realise the shelter is three walls of logs and open to the freezing rain on one side. Squelching socks and underwear are changed, few were expecting the weather to be this bad. The optimistic gent shivering uncontrollably in shorts is facing bitter regret. Soon the guide turns us back. We are not going to make our destination, and the first walk is a literal washout.

Perito Moreno Glacier, Argentina. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

This is soon made up for by a trip from the expensive town of El Calafate to Los Glaciares national park – home to the Perito Moreno glacier which is named after an Argentinian scientist, and explorer of formidable achievements, Francisco Moreno. In a land of unreal beauty, the glacier still ranks as one of Patagonia’s most spectacular sights. It’s one of about 50 glaciers that feed into the Southern Patagonian ice fields.

Along with the northern ice fields, they make up the largest ice mass in the southern hemisphere. Rightfully so, it is a UNESCO World Heritage site. The ice is startlingly turquoise. The guide explains it’s down to the thick ice. It absorbs longer wavelengths like the reds, and only the blues and green emerge. You can get right up to the glacier. Periodically, large towers of ice break off and disintegrate thunderously into the water. It’s an overwhelming moment and a few onlookers fight back tears.

When switching between countries, the border crossing from Argentina into Chile is unpredictably lengthy and tedious. Passports are checked and Chilean police get on the bus with a dog to check bags. They don’t look friendly. I assume it is a drugs check. Some passengers look suspiciously sweaty. Others say it is to prevent the import of plant and food matter. No one really knows but it doesn’t prevent speculation. It all feels tense. It is a relief when the police get off and signal to let us proceed.

There is a long walk in Torres Del Paine National Park, 18 km of steep hills and intense heat with a steep 1 km climb at the end. “No Paine, No Gaine” goes the joke. The guide is irritated and short with me. He makes it obvious he would be happier if I dropped out. I am a liability, trailing at the end of the pack with a tendon injury.

The Three Towers in Torres Del Paine, Chile. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

But I have come a long way for this and practically dragged myself up rock by rock, propelled forward by the memory of a photograph. A place so surreally beautiful, I need to know it exists. The Three Towers do exist in Chilean Patagonia. Looking up at the granite shards towering over the milky green waters of the lagoon, something tells me I am unlikely to see anything this beautiful again.

Later we find out that a young girl died the previous day, making this climb. No one knows why but it is a sobering reminder of what could go wrong here. In a stroke of great luck, however, when we do spot the elusive Andean deer and are triumphant when even the local guide says he hasn’t seen one for five years. Majestic condors soar overhead. They are part of the family of vultures, second only to the albatross in wingspan – they inhabit vast territories travelling hundreds of miles a day in search of food.

Elusive Andean Deer. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

Torres Del Paine is home to the world famous and difficult W trail taking in the Three Towers, French Valley and Grey Glacier. Three valleys give the trail its name. It’s one of those bucket list items for many who are there. The hazards of the place are evident daily. Bent and twisted trees are a reminder of forest fires started by careless visitors.

Also read: Gay Tortoises, Sneezing Iguanas and a View of Paradise in the Galapagos Islands

A girl goes missing on the second day, and we see the Chilean police make their way up on their search. She is presumed to have slipped and drowned nearby, and it is an edgy trek back. The campsites are in spectacular locations but beware of the shower and bathroom facilities which offer the promise of luxury. Aggressive queues, band-aids, and clumps of hair in overcrowded showers can soon make staying unclean seem like an attractive option.

Campsite in Torres Del Paine. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

The final leg takes us on a very long bus journey all the way down to Ushuaia – the southernmost city in the world, bordered by the Beagle Channel. There isn’t much of interest here, some shops and overpriced restaurants. At one point it was said only the mad, bad or sad went to Ushuaia. Expeditions to Antarctica sail from here and there is a big naval presence in the city. ]

The infamous Argentinian warship General Belgrano set sail from here in 1982 during the Falklands conflict and was subsequently sunk by a British nuclear submarine, killing 323 men. The BBC Top Gear louts driving a Porsche with the tasteless number plate H982 FKL were famously driven out of Ushuaia into Chile in 2014 by an angry mob.

Ushuaia prison corridor. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

Ushuaia prison cell. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

It is grim but Ushuaia prison is well worth a look. Cold and dark, it housed about 600 prisoners until 1947 and had an oddly symbiotic relationship with the town. Murderers, political prisoners, thieves – they all came here. Hierarchies and internal snobberies were rife in prison life. Those committing homicide believed themselves to be superior to mere thieves. There were classes of thieves – blackmailers, falsifiers and an elevated class of “refined thieves” who had nothing to do with “petty thieves”.

Murderers were divided into those who killed for money, honour or passion. These last were considered the most repentant, and there was a poignant inscription on the prison walls saying, “a moment of weakness, of blinding, of imprudence in love and the whole work is destroyed by our own hands...the only thing that always remains upright is the tragedy of remorse”.

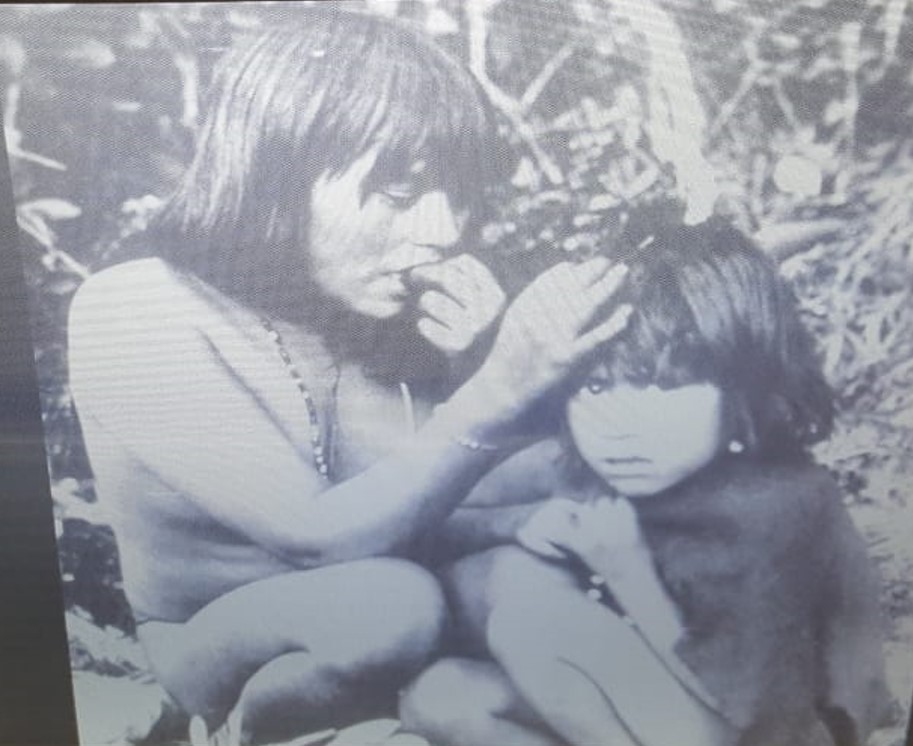

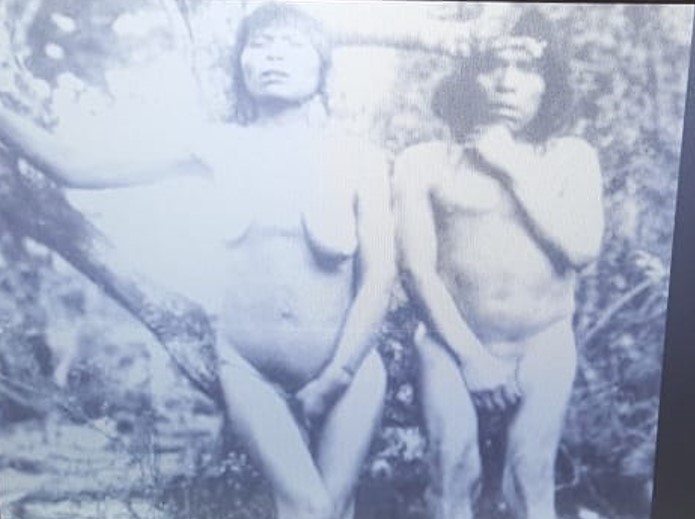

This area was also inhabited once by remarkable groups of tribals, of enduring fascination to adventurers and anthropologists. One such group was the Yamanas who were hunter-gatherers and travelled between islands in canoes and were reputed to be of astonishing physical hardiness, wearing little or no clothing with admirable indifference to the freezing weather – even swimming in the icy waters.

They covered themselves in animal fat and may have had evolved high metabolic rates to adapt to the cold. They were small people, standing no more than five foot two inches reported to have short, rachitic legs but powerfully developed arms and shoulders – particularly the women – as a result of adaptations to a life spent crouching in canoes.

Yamanas. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

Early visitors were scathing in their descriptions of startling cruelty pronouncing them as “short and ugly, figures of crooked and contracted legs in who Darwin was thought to have found the missing link”. They were contrasted unfavourably with their more northerly neighbours, the Onas and Selkman who were described as “well built, with distinguished features and owners of a self-assured arrogance in their walk and gestures”.

Naked Yamanas adapted to freezing conditions. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

Such descriptions served as an excuse to argue for the extermination of the ‘sub-human Indians’ or at least to plead for the funding of Christian missions to civilise. These were duly established and proved to be the final tragedy for a people uniquely adapted to their harsh and unforgiving climate. Where the rain and fire previously kept them hygienic, the damp and dirty western clothes encouraged the spread of disease. So did living in cramped housing.

Also read: A Traveller with Heart: Remembering Anthony Bourdain

The natural hardiness of the Yamanas was no match for the epidemics of flu, pneumonia and tuberculosis that broke out, brought in by the Westerners. The tribe was all but annihilated. A collection of old photos can be found as a tribute in the Ushuaia prison museum, a bleak reminder of the league of extraordinary humans wiped out by ignorance.

Sea lions, Beagle Channel, Tierra Del Fuego. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

There is a final boat journey on the Beagle channel in the Tierra Del Fuego (Land of Fire) archipelago, to islands teeming with birdlife and sea lions. The journey’s end fittingly is where the Argentinian highway, Route 3 ends – a long and dangerous road starting in Buenos Aires and ending in Ushuaia.

The end of the road, Tierra Del Fuego. Photo: Divya Maitreyi Chari and Matthew Angus

The sign confirms – “Usted Esta Aqui Final Ruta 3” (you are here, at the end of Route 3). The trip has had everything – towering mountains, difficult treks, extreme weather, long bus journeys, long boat journeys, fascinating tribes, grim prisons, incredible steak, outstanding wine, mind-blowing glaciers, turquoise lakes, spectacular wildlife. The list of superlatives is long and all fail to do justice to Patagonia. I come away knowing that I have had only the tiniest of glimpses into this wondrous world.

Divya Maitreyi Chari is a neuroscientist and professor of Neural Tissue Engineering at the Keele Medical School in the UK. She has previously published articles on a jungle survival course in British Guyana, and travels along the Bhutan-Tibet border and in the Galapagos islands.

This article went live on June fifteenth, two thousand nineteen, at zero minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.