A Winter’s Day in Patna

It is Makar Sankranti today and so cars are stopping by opposite my sister’s house. This is because a jhuggi has come up across from the house on the pavement that borders the park on the other side of the road. A man and a woman have set up their shelter there, a yellow tarp stretched from the park wall over the pavement. This jhuggi has been here for nearly half a year. The couple have four young children, the youngest only a week old. The cars that stop offer blankets or sweets or fruit to the couple in the jhuggi. I see that the jhuggi is performing a valuable social function: it serves as a conveniently-located roadside drop for the well-to-do who want to perform charitable acts.

The man who lives in the jhuggi is named Biroj. He told me his family has no access to water or electricity. He gets water from inside the park. They came to Patna from Sonbhadra in Uttar Pradesh. Biroj sometimes gets a dishwasher’s job with the restaurants in the area. His wife said that it has been difficult in the cold to keep the baby warm. When I was talking to her she was heating water on a stove to wash the baby’s face. Their other children are very young, all seemingly less than five years old, and they have been taught to beg. I haven’t had a single experience with them over the past few days during which I haven’t been subjected to a high whining tone, each kid trying to wheedle something out of me. I’m sympathetic to the family’s needs but the endless, insistent beseeching has proved testing for my liberal sentiments.

A little while ago, traffic was stopped on the road in all directions. A swift cavalcade of cars came by and made an awkward turn into a lane nearby. My sister said that Chirag Paswan must be hosting a chura-dahi party for Makar Sankranti and the governor had just arrived. Paswan’s home is the one I pass in the morning on my way to the park for a walk. The park is a place where I keep my eyes and ears open. It is difficult to keep one’s ears open when the passing men shout Jai Shri Ram at a rather challenging decibel level. But I like listening to more ordinary conversation. This morning, a man sitting on a bench in the park was saying into his phone: “Kekar ghar mein ladai nahi hai? Kekar ghar mein lobh nahi hai? (Where is the home where there is no strife? Where is the home where there is no greed?)"

Such wisdom! Welcome to the land of the Buddha!

Also read: Bangladeshi Modern Art Starts Its Revolution – From a Basement

I have been driving around town and am always startled by the explosion of commerce, the busy collection of high-end stores and eateries. You can pass through large sections of the town that appear asleep even at eight in the evening; but then there are other places where electronic ads for expensive fabrics and jewellery light up the night sky. In crowded markets, I have observed this time the saffron flags with an angry Hanuman. Also, the more exclusive baristas and a swank-looking new mall. But there is also space for the less well-heeled masses. Last night, I went to Patna’s Marine Drive. A broad avenue called Atal Path curves around the edge of the neighbourhoods familiar to me from my youth and then you arrive at a promenade on the banks of the river Ganga framed by a long row of lights.

Let’s not exaggerate the reality: Ganga has slipped far away from town. You cannot really see the river; you have to imagine it. Meanwhile, there is a river of humanity close at hand on Marine Drive. There is a brightly-lit sign that says “I heart चका चक Patna.” (I liked the mix of languages in that slogan; it felt like home.) After that sign, there were unending rows of stalls and kiosks selling everything from litti-chokha and litti-chicken to momos and noodles. I also saw a horse that exuded the patience of a gentleman who has retired from a job in something like Indian railways; he bore what life pressed on him with an air of quiet resignation and even acceptance.

This evening has been different. I went to a cafe next door and met with some old friends. These friends have been active in left circles for decades. There was Nivedita who has long practised journalism in Bihar, a pioneer in feminist reporting, and her younger sister Mona Jha who has been active in theatre. Mona’s husband Javed Akhtar Khan has now retired from teaching Hindi literature in college and is collaborating with Mona on new theatre projects. Also joining us for a while before rushing off to the clinic where he volunteers was Nivedita’s husband, Dr Shakeel. The good doctor has long fascinated me because from Patna – a place that many would consider a cultural backwater – he went to Angola in 1981 because, as he says, Patna in the 1970s and ‘80s was “a bastion of revolutionary middle-class intelligentsia”.

While I was ordering coffee at the counter, I could look out of the cafe’s glass walls. Darkness had fallen and the couple in the jhuggi had lit a fire to keep themselves warm. A motorcycle stopped and the rider gave the couple a small white polythene bag.

I sat down with my friends and we talked about Patna. In the first 10-15 years after independence, there had been great energy and enterprise in Patna. Those years saw the construction of institutions like the Premchand Rangshala, Rabindra Bhavan, Raj Bhasha Parishad, and even the Moin-ul-Haq stadium. In the years that have followed, there has been decline and even devastation in the name of development. Recently, a part of the famous Khuda Baksh Library was demolished to make way for the proposed metro. The old Dak Bungalow with its famous Dutch architecture has disappeared. Nearly all the bookshops have been closed. There were words offered in praise of the old Coffee House where poets like Phanishwar Nath Renu and Nagarjuna would gather and recite poems. I told my companions that they ought to read my novel My Beloved Life: I pay tribute to the Coffee House and the poets in that novel. In a fit of candor, my comrades confessed that they hadn’t yet got around to reading my book but promised, somewhat recklessly, that they were going to read it soon.

Also read: Drawing a Line: An Evening With Joe Sacco

Our coffee had been drunk. I wondered whether the politicians had finished their chura-dahi dinner at the end of the lane. When I looked out, I could see that the fire outside the jhuggi had been reduced to dull embers.

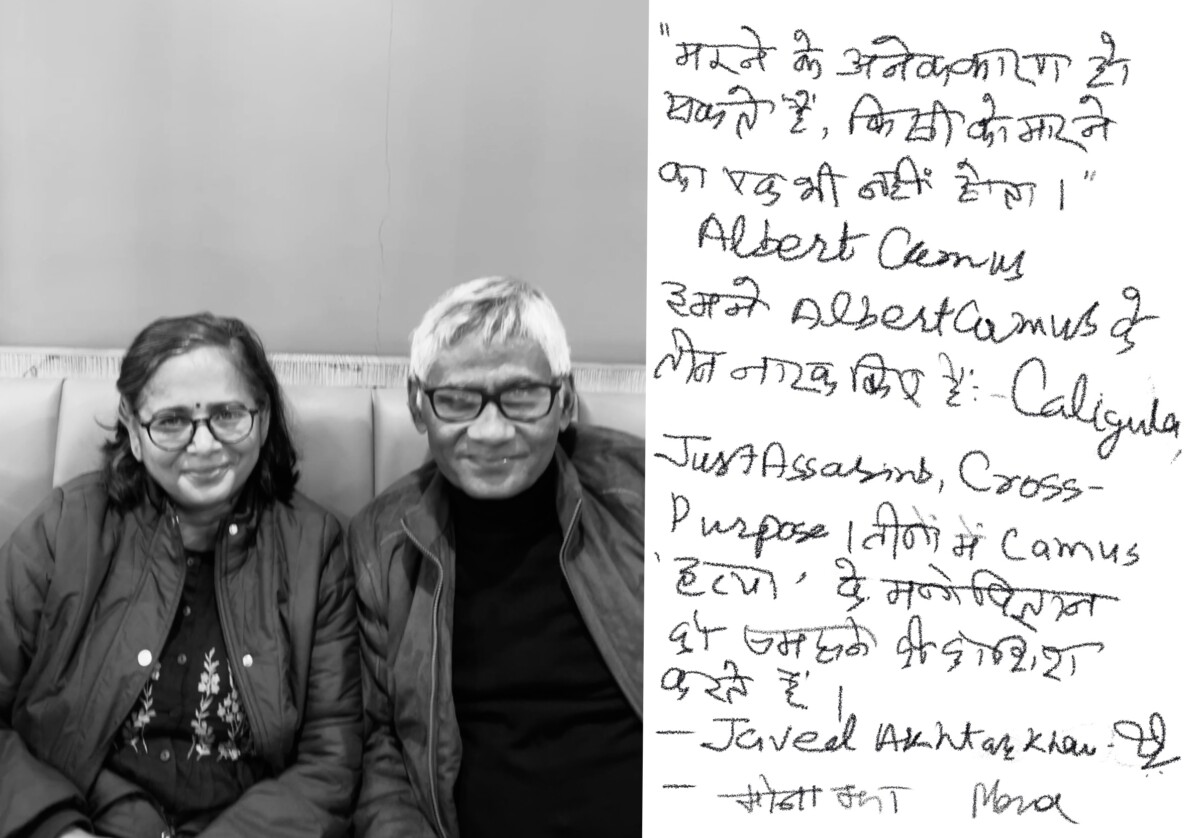

I told my friends that one day soon I would once again like to watch their plays. Javed and Mona have been rehearsing and presenting works by Albert Camus. Why Camus? Javed said that the French-Algerian writer had said that there can be many reasons for dying, but no real reason for killing. In their work in the theatre, they were trying to work toward an understanding of violence, in particular the social-psychology of murder. I asked Javed and Mona to write this down in my diary. Then, we said goodbye and stepped out of the cafe. Two of the older kids from the jhuggi were standing on the pavement and they came close with hands open for begging.

Amitava Kumar is the author, most recently, of the novel My Beloved Life.

This article went live on January fifteenth, two thousand twenty five, at ten minutes past ten in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.