Five Challenges India’s Cities Must Overcome to Unlock Their True Potential

Cities are expected to generate up to 70% of new jobs in India, contribute about 70% of the country’s GDP and drive a near four-fold increase in per capita income by 2030. It is an indisputable fact that facilitating better urbanisation is fundamental to achieving socio-economic prosperity and sustainable development.

But India’s urbanisation opportunity is jeopardised by severe gaps in urban public infrastructure and services, the consequences of which are witnessed in our cities every day. Though policymakers and opinion leaders are starting to wake up to this reality in our cities, their focus on a ‘quick-fix’ approach often ignores the root causes and results in our cities grappling with the same challenges year after year.

Need for a city-systems paradigm to fix urban India’s challenges

Cities are complex systems with several inter-connected sub-systems that help govern a city and drive quality-of-life outcomes. Therefore, to solve quality-of-life issues such as poor mobility and air pollution, it is imperative that we address issues that lie within such systems.

This is where the city-systems framework comes in; it comprises four components – spatial planning, municipal capacities (both human and financial), political leadership and lastly transparency, accountability and participation. City-systems, which helps diagnose and solve urban governance issues sustainably, provides two significant advantages over how challenges are addressed today.

First, it envisages a multi-disciplinary, multi-pronged approach to problem-solving. Second, it unearths root causes and symptoms across multiple levels, helping sharpen transformational reforms. To be able to provide a good quality of life to its citizens, cities need to adopt a systems approach.

The pace with which governments have brought in systemic reforms in urban governance has been painfully slow. The Annual Survey of India’s City Systems (ASICS) 2017, a study that evaluates urban governance using the City-Systems framework, reveals just this – the average score of 23 of India’s largest cities has risen from 3.4 in 2015 to just 3.9 on ten in 2017. The study also identifies five systemic challenges that need to be overcome if India’s cities are to realise their true potential.

Lack of a modern, contemporary framework of spatial planning of cities and design standards for public utilities

Well-made and well-executed Spatial Development Plans lie at the heart of economically vibrant, equitable, environmentally sustainable and democratically-engaged cities. ASICS shows that spatial planning is the weakest of City-Systems, with Indian cities scoring an average of 2.9 while the benchmark cities (London, New York and Johannesburg) score 7.1 on ten.

There are two broad aspects that have resulted in a lack of robust planning in India – which according to a UNEP report, may be costing us up to 3% of our GDP every year. One is weak governing legislation in the form of Town and Country Planning Acts (T&CP), most of which are decades old and do not mandate the creation of layered plans at the municipal and ward level. Sections on plan violations and penalties – one of the most crucial elements of zoning principles – are poor and blatantly copied across most states’ T&CP acts.

Vague language and improper devolution of responsibilities in law have resulted in disastrous incidents, most recently in the form of the deadly Mumbai fire. The second aspect is – weak enabling processes to implement and enforce whatever laws and policies exist. For e.g., none of the Indian cities evaluated has a common digital GIS base-map shared among the plethora of agencies involved in delivering services and infrastructure in a city. A Dalberg report states that such maps, even if they lead to a 1% improvement in planning yields, could unlock $270 million in value for municipalities, not to mention the added advantages on account of lower travel times and lower emissions.

Vague language and improper devolution of responsibilities in law have resulted in disastrous incidents, most recently in the form of the deadly Mumbai fire. Credit: PTI

Exacerbating the challenge brought about by these two aspects is an absence of uniform urban design standards for crucial public utilities, such as urban roads and footpaths, in master plans and across the municipal corporations.

Weak finances, both in terms of financial sustainability and financial accountability of cities

Cities need significant amounts of capital to invest in not just creating new infrastructure and catching up on service delivery deficits, but also for revenue expenditure such as operations and maintenance and hiring of talent. The High-Powered Expert Committee 2011 report estimated India’s urban infrastructure expenditure requirement is at Rs 39.2 lakh crores. Our study revealed that India’s cities fare poorly on two counts related to finances – generation of revenue, management of the resources they generate.

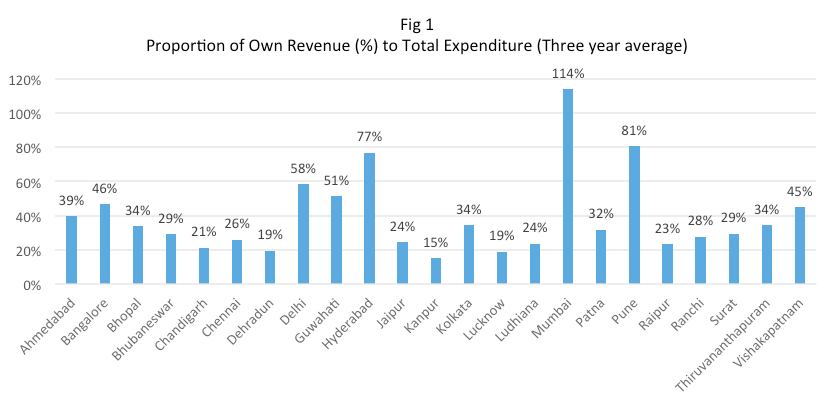

First, as is evident in Figure 1, the cities assessed in ASICS generate only 39% of the funds they spend, leaving them highly dependent on state and central government grants. Several cities do not even generate enough resources on their own to pay the salaries of their staff. This inability to generate funds ultimately affects their ability to spend adequately towards capital expenditure as can be seen in Table 1.

Smaller cities, that are likely to see a bulk of urbanisation, spend less than half as much as bigger cities. The second issue, of poor money management, is evident in the acute lack of Medium/Long Term Fiscal Plans (MTFP/LTFP), which no other city barring Guwahati no other city has, and the high budget variance figures seen across cities – some as high as 75%, in the cities of Ranchi and Raipur.

| Type of Indian City | Average Per Capita Capex (INR) |

| Mega (5+ MN population) | 2,209 |

| Large (1+ to 5MN Population) | 2,335 |

| Medium (Up to 1MN population) | 1,385 |

Table 1: Capital expenditure per capita as a year average

Poor human resource management, in terms of number of staff, skills and competencies of staff, organisation design and performance management

Our cities do not have an adequate number of skilled staff with an estimated average vacancy figure of 35%. In some cities, this is as high as 60%. Their HR policies are outdated and systems and processes broken. None of the cities assessed in ASICS has cadre and recruitment rules that contain modern job descriptions covering both technical skills and managerial competencies for each role or position in the municipality.

The average urban experience of a city’s administrative head, the Municipal Commissioner stands at just 2.7 years and only has an average tenure of 15 months, barely enough to just know the lay of the land. As shown in Table 2, this is more evident in medium-sized cities.

| Type of Indian City | Average urban experience (years) | Average number of commissioners in the last five years |

| Mega (5+ MN population) | 4.1 | 3 |

| Large (1+ to 5MN Population) | 2.9 | 4 |

| Medium (Up to 1 MN population) | 1.2 | 5 |

Table 2: Average urban experience vs Churn of the Municipal Commissioner

Powerless mayors and city councils and severe fragmentation of governance across municipalities, parastatal agencies and state departments

In theory, city governments are led by the city Mayor/Council. This model, which is the common governance mechanism in most cities is widely accepted as delivering some of the best quality-of-life based outcomes. Indian cities, however, are managed by a spectrum of disorganised government bodies and parastatals (such as water, transport and development authorities) run by the state government through which they often influence city affairs and policy.

While transparency, accountability and participation are at the core of democratic governance, India’s cities fare poorly on all counts. Credit: Reuters

The mayor ends up being a glorified figurehead and the city government, a glorified service provider with an acute lack of funds, functions and functionaries. ASICS shows that, on average, only nine out of the 18 functions under the 74th CAA have been effectively devolved and that mega and wealthier cities, as seen in Table 3, have relatively weak Mayors, compared with medium-sized and less wealthy cities. The average Indian city, for its fragmented state of governance and weak local bodies, pays a hefty price.

| Factor | Large and Medium City | Mega City |

| Proportion of cities with a five-year mayoral tenure | 78% | 20% |

| Proportion of cities with a directly elected mayor | 33 | 0 |

| Average score for taxation powers | 8/10 | 8/10 |

| Average of own revenues to total expenditure (%) | 31% | 67% |

| Average per capita capex (Rs) | 1,966 | 2,209 |

| Average number of functions devolved | 8/18 | 11/18 |

| Average score for powers over staff | 4.3/10 | 5/10 |

Table 3: How empowered are our cities and their leaders?

Total absence of systematic citizen participation and transparency

While transparency, accountability and participation are at the core of democratic governance, ASICS reveals that India’s cities fare poorly on all counts. There are no structured platforms for citizen participation (ward committees and area sabhas), no coherent participatory processes (such as participatory budgeting), weak citizen grievance redressal mechanisms and very low levels of transparency in finances and operations.

An absence of a strong component of transparency, accountability and participation have resulted in weak levels of engagement between citizens and governments, therefore low levels of trust and in general tarnished democratic values of a city.

How to put the city-systems to work in our cities?

ASICS 2017 clearly highlights the need for strengthening city-systems in our cities. While the project focus taken by most urban missions such as the erstwhile JNNURM and the current AMRUT and smart cities missions is important, there needs to be equal, if not more, attention paid to systemic reforms which are currently lacking.

And while the Central government can lead the way by framing model laws and policies, state governments must hold the beacon for driving institutional reforms in spatial planning, fiscal decentralisation, overhauling cadre and recruitment rules for municipalities, empowering mayors and municipal councils, and instituting decentralised platforms for citizen participation (ward committees and area sabhas). ASICS can help state governments and city leaders design a reforms that suits their city best.

Urban India cannot afford to continue missing the wood for the trees. The key to vibrant cities is replacing the current approach of tactical stabs with a long-term and sustainable ‘city-systems’ approach.

Vivek Anandan Nair, V.R. Vachana and Santosh Rao are part of Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy, Bengaluru and authored the Annual Survey of India’s City-Systems Report 2017.

This article went live on April fifth, two thousand eighteen, at zero minutes past four in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.