In Era of Bulldozer Raj and Forced Evictions, Reality of Urban Slums Paints a Bleak Picture

This article is part of a series studying the effects of urbanisation, climate change induced risks and rising informality on India’s vulnerable and marginalised communities. The subsequent articles in the series shall focus on impact of unplanned urbanisation on street vendors, unregistered workers, migrant communities and targeted incidents of discriminations to specific communities living in informal settlements.

In early September 2025, thousands of residents in the Vasant Vihar slums of Delhi received eviction notices from municipal authorities, creating widespread anxiety among communities who have lived there for decades, raising urgent questions about livelihood security and urban rights.

This episode highlights a persistent dilemma in Indian cities: as urbanisation accelerates, slums – home to millions – stand at a crossroads of enforced state displacement, and invisibility despite their critical role in shaping the core of India’s urban fabric.

The Delhi government’s August pledge that “no slum will be razed without rehabilitation” introduces a tentative promise of hope but also scepticism among advocates who have witnessed too many broken promises may find the promise itself less comforting at a time when bulldozer raj and ad hoc state coercion has replaced any faith in a rights-based discourse or inclusive development for those kept at the margins.

Slums in India have grown in scale and prevalence alongside rapid urbanisation, accounting to a quarter of India’s urban population. This growth is driven by multifaceted causes, including the inability of formal housing markets to keep pace with demand, persistent poverty, ineffective urban governance, and significant migration from rural areas and smaller towns in search of economic opportunity. Shortfalls in city planning and limited investment in affordable housing have meant that informal settlements regularly emerge on vulnerable, peripheral locations with limited access to infrastructure or services.

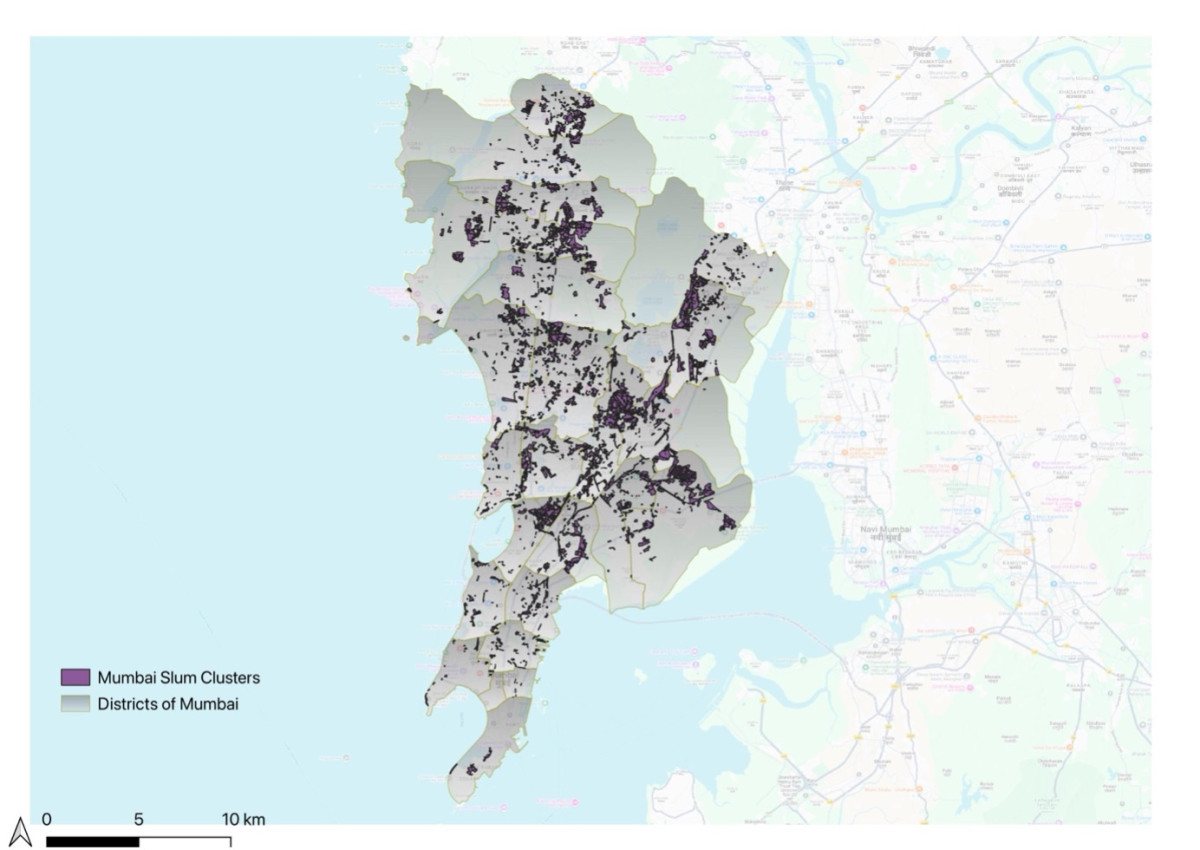

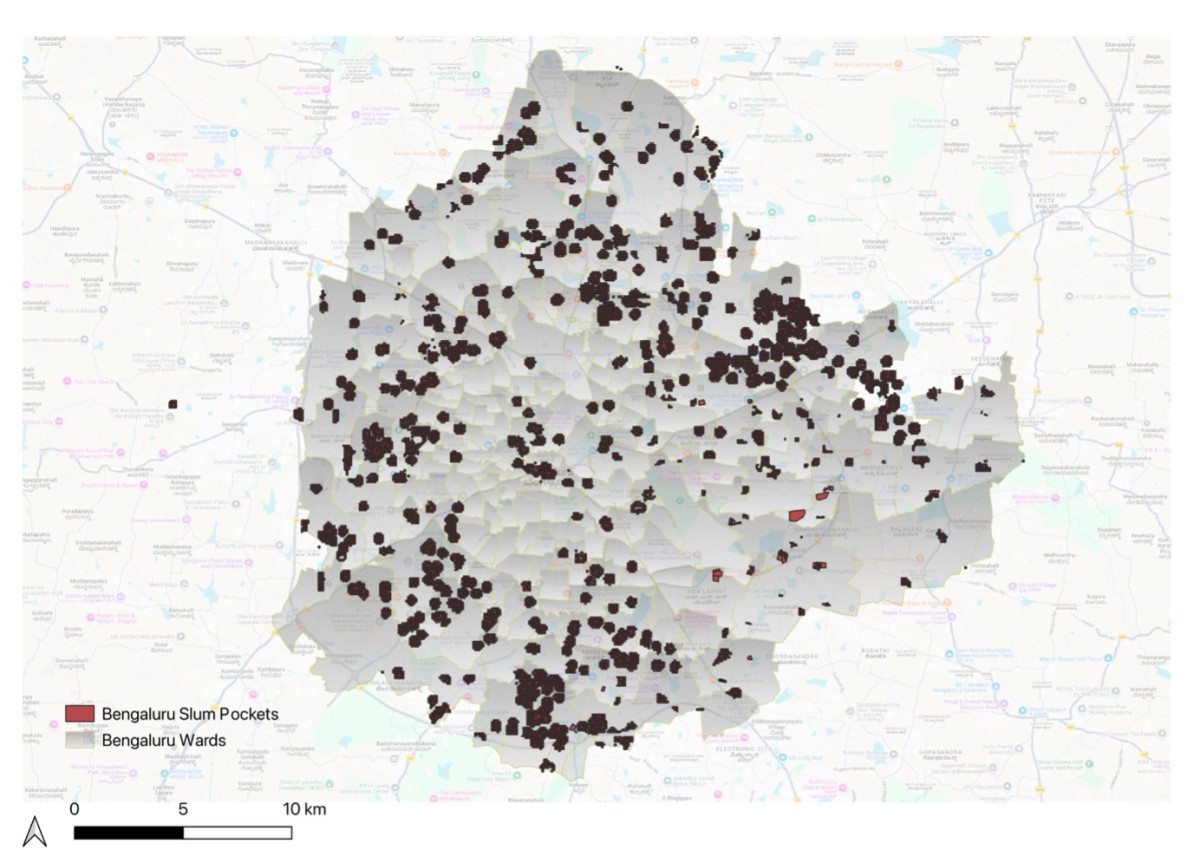

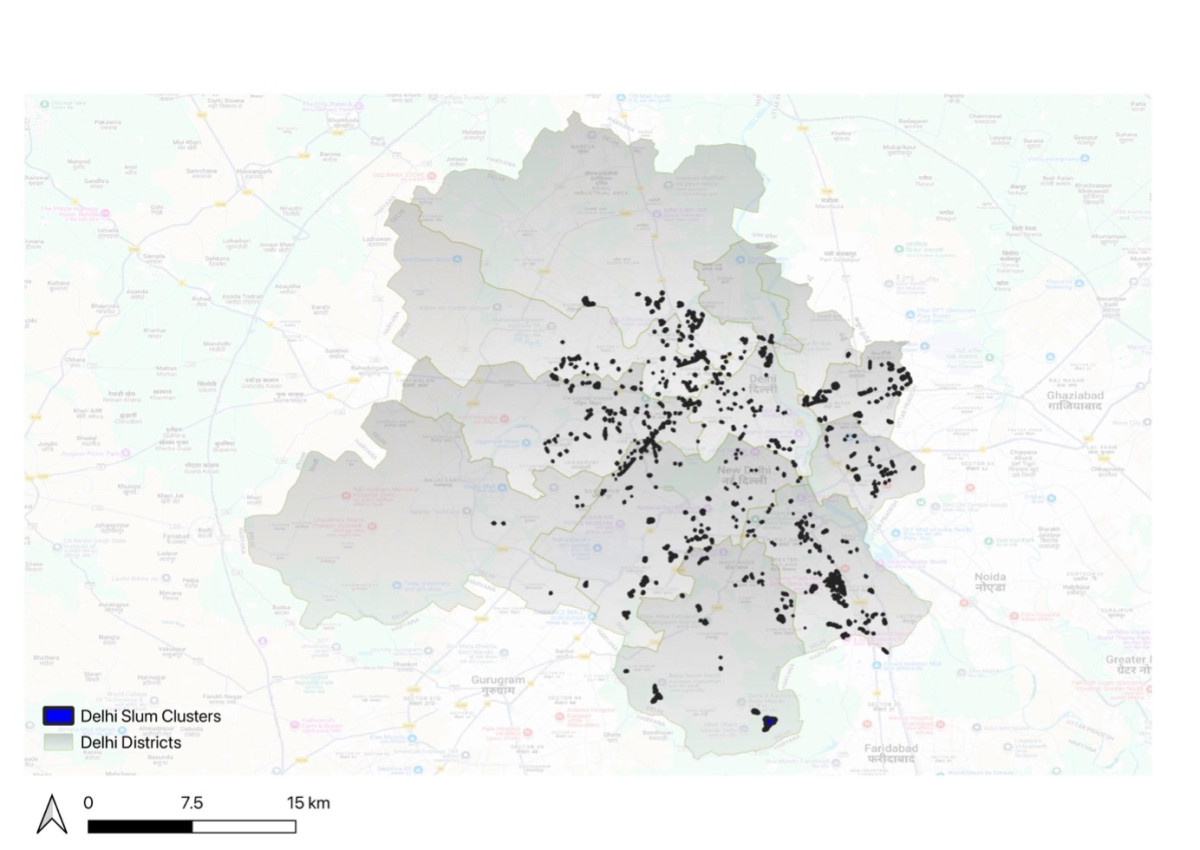

Slums in Indian cities are typically either prominently visible in city centres or located on the urban peripheries, where the majority of informal settlements emerge and grow. Maps of slum locations in Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru show a clear pattern of the majority of slum locations of slums around the city peripheries. In Delhi, a large share of the population resides in “unplanned colonies” and non-notified slums primarily inhabited by rural migrants.

While some slums exist within the central zones, a significant number are concentrated in peripheral areas such as the South, North and West zones – regions characterised by more open government land and less threat of eviction, making them affordable and accessible to low-income migrants and informal settlers.

Similarly, Mumbai’s iconic Dharavi slum is centrally located and well-known, but a vast number of newer and rapidly expanding informal settlements exist on the city’s outskirts, forming a critical part of its urban landscape.

Bangalore also shows a pattern of slum growth largely in peripheral industrial and suburban zones where affordable land and labour opportunities attract migrants and informal workers. Over time, these slums become organically absorbed and integrated into the broader city fabric, reflecting a process of urban expansion and informal urbanisation that contributes to the complexity of city growth.

A key challenge exacerbating this situation is the existence of non-notified slums. Unlike notified slums, which qualify for formal inclusion in census counts, development programs, and social protections, non-notified slums remain unrecognised and unsupported, leaving residents exposed and marginalised.

Many non-notified slums lie on the urban fringes where rapid city expansion and incoming migrants find informal shelter. These settlements are rarely mapped or considered in municipal planning, obscuring the true scale of precarious urban living and neglecting significant populations when allocating resources.

The official numbers on slum dwellers significantly undercount those living in non-notified slums, resulting in policy blind spots that perpetuate exclusion.

Poor urban governance exacerbates these vulnerabilities. Fragmented authorities, outdated planning regulations, weak enforcement, and a lack of coordination among agencies create systemic failures that allow slums to proliferate while hindering efforts to improve living conditions.

Slum residents often remain outside formal urban benefits despite their vital contributions to city economies and societies. Governance gaps also manifest in the ambiguous tenure status of slum dwellers, enabling frequent evictions without rehabilitation or compensation, as has been tragically evident in Delhi’s ongoing eviction drives.

Beyond mere housing, slums are integral to Indian urban economies through their symbiotic relationship with city supply chains and market spaces. Informal work concentrated in and around slums includes street vending, production, repair, and recycling, all essential for urban consumption across social strata.

Cities operate in a duality of formal and informal economic spaces: slums are not peripheral anomalies but urban anchors supporting livelihoods and enabling flexibility in large, complex economies.

Significantly, slums must be recognised not as zones of deviance or criminality, but as vibrant, productive parts of the city. The dominant “slum-free city” narrative undermines this reality, often justifying exclusionary or demolitive policies.

Ignoring the economic and social functions of slums leads to disruptive displacement and disrupts the very systems that sustain urban life. Research demonstrates that ambitions to eradicate slums under this model result in forced evictions, disruption of livelihoods, and community disempowerment without addressing the root causes of informal settlements. Depicting slums only as areas of crime and disorder overlooks their complex social structure and the positive economic roles they play.

This narrow perspective can lead to misguided urban policies that increase marginalisation. To promote inclusive urban development, it is essential to create policies that integrate informal settlements rather than eliminate them. This approach should focus on gradual improvements, securing tenure rights, and leveraging the economic potential of informal workers.

The recent eviction threats to slum residents across Delhi occur against this backdrop of contested urban priorities. While the Delhi government’s announcement promising no demolition without rehabilitation and the allocation of nearly 50,000 refurbished flats for eligible slum dwellers offers a framework for change, advocates caution that implementation and genuine participation remain critical.

Integrating slums into urban planning is crucial because they play a vital role in the supply chains, markets, and labour systems of cities. By implementing gradual upgrades, encouraging community participation in the planning process, and granting legal recognition to both informal work and market spaces, we can create healthier, more resilient, and equitable urban environments.

Policies should reject the idea of a slum-free city and instead focus on urban development strategies that promote social inclusivity.

It is important to recognise that both formal and informal coexist and cohabitate in urban spaces. The binaries may exist in our minds or in state action but their existence is a natural occurrence in shaping the heart of cities, the informal network, as essential as it is, remains complementary to the organised, formal network. To create safer and more equitable cities, we need more well-funded and participatory planning that connects these networks in a holistic manner while ensuring any such integrative approach respects each stakeholder’s rights giving slum residents too equal access to opportunities for a live with dignity.

Namesh Killemsetty is an Associate Professor and Associate Dean (Academic Affairs) at Jindal School of Government and Public Policy, O.P. Jindal Global University.

Deepanshu Mohan is a professor of economics, dean, IDEAS, and director, Centre for New Economics Studies. He is a visiting professor at the London School of Economics and an academic visiting fellow with AMES, University of Oxford.

Najam Us Saqib is a Phd scholar at Central University of Kashmir. He is a Senior Research Analyst with Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES), OP Jindal Global University.

This article went live on September twenty-second, two thousand twenty five, at one minutes past twelve at noon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.