Born in 1946 in Shahidanwali village in Punjab (now in Pakistan), Kamla Bhasin grew up in Rajasthan. After completing her post-graduation from Rajasthan University, she studied sociology in Germany and on her return in 1972 joined the Udaipur-based voluntary organisation Seva Mandir, which worked with the rural and urban poor – men and women – with the goal of “mobilising them for their own development”. From that point till September 25, 2021, when Kamla Bhasin, suffering from cancer, breathed her last, her life was a seamless journey of, in her own words, “being deeply engaged with issues related to gender, development, peace, identity politics, militarisation, human rights and democracy”; of exploring and articulating “connections between different issues and to promote synergies between different movements.” It was a journey during which the indefatigable feminist touched countless hearts. One of them was Kalpana Viswanath whose tribute to Kamla Bhasin looks back at three decades of association with her.

§

I met Kamla Bhasin in 1990. I was 25 years old, new to Delhi, and wanting to do my doctoral dissertation on the women’s movement. As I asked around, it was Kamla’s name that came up most frequently in conversations.

She was universally described as an unflagging feminist and one of the most original voices to have emerged in the course of the women’s movement in the 1970s, who had the ability to rip through ideas of patriarchy with rapier sharp wit or laughter.

By the time I met her, Kamla had already spent over two decades in the thick of the feminist movement. She had been an integral part of spirited and sustained campaigns during which women’s groups had made the streets their own in protest against dowry, rape (following the Mathura rape case) and domestic violence. Their protests highlighted the feminist slogan “the personal is political”. I was eager to meet Kamla Bhasin.

My first meeting with her was at a women’s demonstration at India Gate (yes, we could protest there in those days). The long banner that the activists were holding was actually a sari on which they had painted slogans of women’s rights. It was an arresting sight.

I was struck by how the ubiquitous sari that draped the bodies of women across the caste, class and religious spectrum had become a canvas for making a collective statement about the body politic. Like most people who met Kamla, I too fell a little in love that day. Kamla, though, always exhorted us to rise, not fall, in love!

After the protest ended, Kamla sent me off to Jagori, a pioneering women’s collective she had co-founded in 1984 with six other fellow travellers in the women’s movement.

After the protest ended, Kamla sent me off to Jagori, a pioneering women’s collective she had co-founded in 1984 with six other fellow travellers in the women’s movement.

The more I learnt about the collective, the more I was drawn to its ideas.

Jagori was animated by the idea of taking feminist consciousness to rural areas and small towns and bringing activism and theory closer to each other.

One of its crucial areas of work was feminist training through participatory workshops with women, taking a cue from the way women learnt.

Interestingly, one of Jagori’s biggest strengths was multimedia communication long before the word became fashionable – it succeeded in communicating the densest of feminist ideas simply, through song and music, poetry, posters and feminist-themed diaries, to appeal to a wide audience.

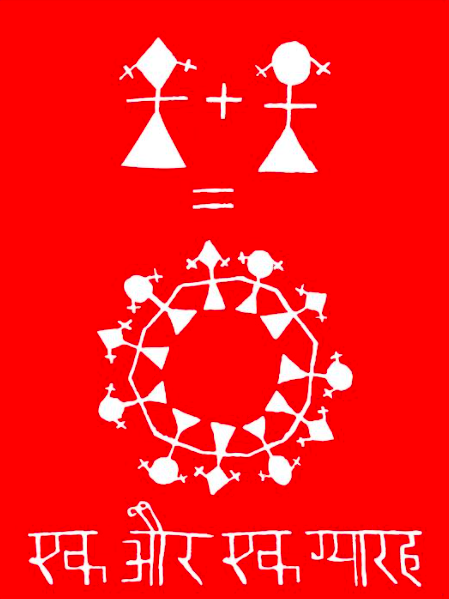

Poster text by Kamla Bhasin and design by Bindia Thapar, produced by Jagori.

Those were heady times. The Bhanwari Devi rape case had brought together women’s groups from Delhi and Rajasthan in 1992.

Their fiery and sustained campaign to secure justice for Bhanwari Devi, who worked as a ‘saathin’ for the Rajasthan government’s Women’s Development Programme, ultimately resulted in the 1997 Supreme Court guidelines addressing sexual harassment at the workplace (the Vishaka guidelines). In 1996, we as women’s activists took to the streets in protest against right wing groups that had vandalised theatres screening Deepa Mehta’s film Fire for its portrayal of a lesbian relationship.

I also have a vivid memory of an International Women’s Day celebration during that period when we had a ‘mashaal’ march from Sarojini Nagar market to the ‘AIIMS circle’ (which was actually a crossroads close to the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, before the age of flyovers.) I can never forget the sight of Kamla climbing the traffic police booth in the middle of the road, her full-throated slogan meri behne mange azaadi (my sisters demand freedom) reverberating in the air.

It was a slogan Kamla had heard from feminists in Pakistan; she popularised it and made it into a feminist anthem which continues to be used in movements even today.

Kamla’s creativity was boundless. She penned more than 200 songs, many during feminist workshops, which have been sung at protests and events not only in India but across South Asia, and have even been translated into more than 10 languages.

Those songs meant so much to young activists like us who were privileged to see how Jagori was attempting to bridge the distance between theory and activism. Her song Tod tod ke bandhanon ko, dekho behne aatee hain (breaking their restraints, see, the sisters come) made us feel that we could indeed break all the conventions and normative shackles that held us back from our journeys as women.

And that was how we bid her farewell at her funeral on September 25 – we sang that song and many more feminist songs to give a truly fitting send off to a woman who had celebrated life in spite of all its tribulations.

One of Kamla’s most endearing characteristics was her openness – to people and to viewpoints. She was not dogmatic and did not toe any particular party line. She truly listened to people and was even open to being told off! In my early years at Jagori, once Kamla called me at home around 10 pm when I was putting my daughter to bed. My daughter picked up the phone and told her, “This is not the time to call my mother!” I quickly snatched the phone to apologise to Kamla and was pleasantly surprised when she apologised and said my daughter was correct. She never called me at that time after that incident.

Poster created by Kamla Bhasin and Bindia Thapar, produced by Jagori and Sangat.

Across countries and movements, activists felt that she was one of them. One of Kamla’s biggest passions was the idea of creating peace and harmony in South Asia, exemplified in one of her posters that said, “Walls turned sideways are bridges.”

She dedicated much of her life to building bridges in the region, whether at the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations, where she worked from 1976 to 2001, supporting innovative NGO initiatives aimed at the development and empowerment of those at the margins, especially women, or later when she set up Sangat (South Asian Network of Gender Activists and Trainers) in 2002 to continue the important task of creating more space for transformative work in the field of gender.

Thousands of women from across South Asia have been part of Sangat workshops and have forged bonds of friendship that have translated into collaborative work including workshops, research and campaigns.

It was she who had the idea of celebrating November 30 as South Asian Women’s Day as part of the global ‘16 Days of Activism against Gender-based Violence’ commemorated between November 25 (International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women) and December 10 (International Human Rights Day). Kamla was also instrumental in bringing the One Billion Rising (OBR) campaign to end sexual violence (launched in 2012 to get a billion women to raise their voices together) to the region.

Poster created by Kamla Bhasin and Bindia Thapar, produced by Jagori for the UNIFEM campaign.

She was also part of so many South Asian initiatives for peace, be it the Women’s Initiative for Peace in South Asia (WIPSA), Pak India People’s Forum for Democracy and Peace (PIPFDP) or South Asians for Human Rights (SAHR). The outpourings on social media across the region these past few days is a testament to these efforts which have inspired people to dream of peace and friendship across borders. An important contribution in this regard was made by a book she co-authored with feminist publisher and author Ritu Menon, titled Borders and Boundaries: Women in India’s Partition (1998).

In fact, it was Kamla’s creative energies that allowed her to connect all her fields of action in such a seamless manner. She was not only an orator and communicator par excellence but also a writer, with over 35 books including eight children’s books to her credit.

Poster text by Kamla Bhasin and design by Bindia Thapar, produced by Jagori.

Her books on feminism and patriarchy have been widely distributed along with the feminist song books and posters on the girl child, powered by powerful and evocative messages like Main likhna seekh rahi hun taaki apni kismet khud likh sakoon (I am learning to write so that I can write my own destiny).

Even today, my eyes well up when I read Malu Bhalu, a children’s story about “the brave daughter of a brave mother.” Kamla’s ability to communicate concepts of feminism and patriarchy in such simple language was mindboggling, and she could reach the hearts and minds of millions of people, as she did when she spoke as a guest on the mainstream television programme Satyamev Jayate on issues like domestic violence and masculinity.

To be able to speak in a way that can reach even those who are not like-minded without being patronising is an invaluable skill. In an era of power-point presentations, she would say, “I don’t need power points, I am a power point myself!” She could get any audience up on their feet, sing along, dance and open their hearts, such was the infectious pull of her pithy one liners, jokes, songs and her trademark whistle (which we all tried to learn, failing miserably!).

Feisty campaigner. Photo: From Kamla Bhasin’s Facebook page

Kamla, like all human beings, could also make mistakes. She has been criticised for some of her positions. But Kamla had the rare ability to accept that she could make mistakes. On one occasion she told me, “If I have experienced so much love and affection in my life, I should be able to accept criticism as well.”

Whatever the situation, she let her heart and love guide her. Her feminism was a nurturing one; even those who thought differently experienced it. You could always pick up the phone and talk to her if you disagreed with something she said or did. As much as she gave love, she also got her strength from the love that she got from others. Friendships were central to her life.

Travelling in a group with Kamla was in some senses like being at a party to which everyone was invited!

Along with her words, it is her zest for life, unbounded energy, caring and love, willingness to listen, and honesty that will continue to inspire generations of feminists and activists.

Kalpana Viswanath is a feminist who has been with Jagori since 1990 in different avatars – as a volunteer activist, then Coordinator and now as the Chair of the Board. She is also co-founder of Safetipin.