Al-Qaeda After Al-Zawahiri

Sometime in the late 1980s, I heard one evening that the manager of a famous video store in Peshawar, from whom we used to rent English movies, had been thrashed outside his shop located on the bustling University Road. Though sorry for the man, I didn’t pay much attention to the incident.

The next day details emerged that the hapless fellow had been tormented by a bunch of Arab jihadists because his vehicle had blocked their “Sheikh’s” ingress to the nearby Kuwait Red Crescent Hospital. That sheikh, it turned out later, was Dr Ayman Muhammad Rabi al-Zawahiri, the Egypt-born surgeon who was a leader of the jihadist outfit Tanzeem-al-Jihad.

Al-Zawahiri had been working at the Kuwaiti hospital and apparently at other facilities run by Islamists in Peshawar, honing his surgical skills. But more importantly, he was perfecting the theory and practice of jihadism alongside other Arab jihadist ideologues and militants like the Abdullah al-Azzam and Osama bin Laden, who had descended upon my hometown to support and participate in the so-called jihad against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan.

Al-Zawahiri was born in Cairo in 1951 into a family of accomplished clerics, scholars, and physicians. His paternal grandfather was the Grand Sheikh of the historic Al-Azhar Islamic University, and his father was a professor of medicine. His maternal grandfather Abdul Wahab Azzam (no relation to Abdullah al-Azzam), an eminent pan-Arab scholar and president of Cairo University, was Egypt’s first ambassador to Pakistan.

Ayman al-Zawahiri’s inclination towards extremism, which came at the age of 15, wasn’t for a lack of privilege or a dearth of future prospects. Instead, he was deeply influenced by the 1966 execution of the radical Muslim Brotherhood ideologue Sayyid Qutb for his alleged role in a failed conspiracy against the secular dictator, Gamal Abdel Nasser. He started a group called al-Tanzeem (the Organization) with other high school friends, ostensibly to topple the Nasser regime. The group eventually became known as Tanzeem al-Jihad al-Masri or the Egyptian Islamic Jihad.

Al-Zawahiri completed a medical degree and eventually a masters in medicine from Cairo University in 1978. But his involvement with the radical Islamist movement against Nasser’s heir, Anwar al-Sadat, culminated in his arrest when Sadat was assassinated by a group of army officers at a military parade in 1981. His arrest, torture, and trial by the Egyptian regime would permanently change a radical al-Zawahiri to an extremist wedded to terrorism.

He used the trial to make his mark as an Islamist ideologue, fiery orator, and skilled organiser. The footage of a young al-Zawahiri addressing the judges from his cage to the chants of his fellow prisoners showed the media savvy that was later on display in his slick use of videos and multimedia messages. His emotionally charged speeches during the trial were skillfully deployed – to cast his Egyptian captors as un-Islamic. They were also directed at Western audiences, since the Islamists regarded the US and its European allies as the principal backers of the Egyptian junta and as ultimately responsible for its actions. He was released, however, after a couple of years in prison and took off for Saudi Arabia, where he practised surgery for a year or so before making his way to Peshawar in 1986.

While his immediate objective was to collaborate with the so-called Arab-Afghans fighting alongside the Afghan Mujahideen, his ultimate aim was to exact personal and ideological revenge from Egypt's rulers. He met Osama Bin Laden in Peshawar but wasn’t directly involved with the Azzam-Bin Laden project – supported by Afghan jihadists Jalaluddin Haqqani and Abd-ur-Rab Rasool Sayyaf. This was called the Maktab al-Khidmat (the service centre), and it would eventually morph into al-Qaeda. But he became really tight with Bin Laden, and took off with him to Sudan in 1994 after the fall of Kabul to the Mujahideen. During his years in Peshawar, he continued to work at the Kuwaiti Red Crescent hospital without any hindrance from the local authorities. Like Bin Laden, al-Zawahiri developed close ties with the Pakistan army-backed Afghan jihadists like Jalaluddin Haqqani, the founder of the Haqqani Network (HQN), which was a convergence point of transnational jihad.

Jalaluddin Haqqani (R) points to a map of Afghanistan during a visit to Islamabad, Pakistan, October 19, 2001, as his son Naziruddin (L) looks on. Photo: Reuters/Stringer/File

Once in Sudan, al-Zawahiri turned his focus to Egypt and organised a series of unsuccessful attacks on government officials, which resulted mostly in civilian casualties. In one attack on the Egyptian prime minister, a schoolgirl was killed. This led to public outrage against al-Zawahiri’s brutal tactics and an ideological challenge from less radical Islamists. Al-Zawahiri responded with theological justifications for civilian deaths and also used religious arguments to justify suicide attacks, which are considered forbidden by a preponderance of Islamic scholars. He placed the suicide attacks within the framework of jihad, or traditional holy war, by describing them as Istishhadi or martyrdom missions, in an attempt not only to change tactics but the conceptual paradigm as well. With a sordid irony, Al-Zawahiri then ordered a hit on the Egyptian embassy in Pakistan – a diplomatic mission that his grandfather had pioneered – killing over a dozen civilians in that suicide car-bombing.

But he had a falling out of sorts with Bin Laden, who refused to finance his deadly campaign in Egypt. Both, however, remained together and were subsequently expelled from Sudan. He is said to have travelled to the US and the UK before eventually arriving in Afghanistan, which was by then under the Taliban control. Bin Laden had preceded him there and formally launched al-Qaeda and was working on a declaration of war against the US. The two men made up and vowed to inflict revenge on the US, which al-Zawahiri described as the head of the snake, without whose backing the Arab regimes – the tail of the snake – would not survive.

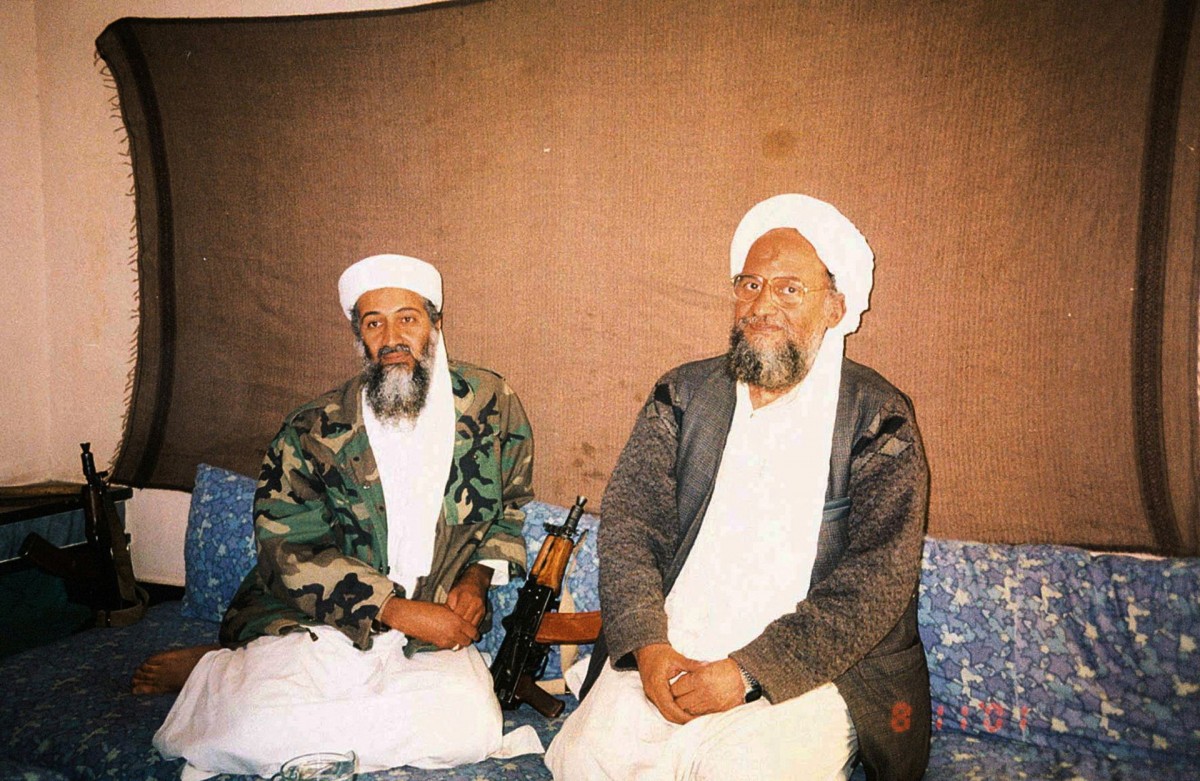

Osama bin Laden sits with Ayman al-Zawahiri during an interview with Pakistani journalist Hamid Mir (not pictured) in an image supplied by Dawn newspaper, November 10, 2001. Photo: Hamid Mir/Editor/Ausaf Newspaper for Daily Dawn/Handout via Reuters.

While the Tanzeem al-Jihad and al-Qaeda remained separate entities, the collaboration between the two increased. After declaring war on the US through a fatwa in 1998, they attacked the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania that year, and the USS Cole in 2000. The US responded by cruise missile attacks on the Arab-Afghan bases in Afghanistan and Sudan but failed to nail the lynchpins.

The formal merger of Tanzeem al-Jihad and al-Qaeda took place somewhere in mid-2001, and al-Zawahiri became a deputy to Bin Laden, superseding several core members of the terrorist group, including the operational honcho Sayf al-Adl. For all practical purposes, al-Zawahiri acted as chief operating officer to the CEO Bin Laden. While both were extremist ideologues in their own right, Al-Zawahiri’s strong doctrinal base perhaps gave him a deadly edge over his leader in waging what they described as the offensive jihad. Al-Zawahiri championed the most violent form of Islamist radicalism and was rightly considered to be the mastermind of the deadly 9/11 attacks, killing and maiming thousands of innocent civilians. And after the US invasion of Afghanistan in retaliation, al-Zawahiri organised the retreat and regrouping of al-Qaeda in the Pakistani regions bordering Afghanistan. He took the helm as al-Qaeda’s chief for a decade after Bin Laden’s assassination by US Navy SEALS in May 2011. His elimination in a US drone strike in Kabul this past weekend has answered a few questions, while raising several more.

That al-Zawahiri was killed in a house owned by a Haqqani Network man, in the heart of Taliban-ruled Kabul, confirms that the Taliban has not and will not sever its ties to al-Qaeda. A UN report just last month had clearly noted that “Al-Qaida’s leadership prospects have eased, and Aiman [sic] al-Zawahiri is confirmed to be alive and communicating freely,” and that “al-Zawahiri’s apparent increased comfort and ability to communicate has coincided with the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan and the consolidation of power of key Al-Qaida allies within their de facto administration.” Instead of dissociating the Taliban emirate from the al-Qaeda leader’s presence in Kabul, its spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid was swift in condemning the US drone strike hours after it was conducted.

While the Taliban has been pretending to be a new and improved outfit seeking international recognition and assistance for its regime, it would have lost face with its cadres if had collaborated (or been seen to be collaborating) with the US against its longtime jihadist ally. With Sirajuddin Haqqani – a staunch al-Qaeda ally – as the interior minister and assorted others from his network in key government positions, high-level Taliban cooperation with the US can be ruled out fairly certainly. Al-Zawahiri was suspected to be hiding, likely with the Haqqani Network, in the regions straddling the Durand Line since his escape from Tora Bora in 2001. In fact, one of his wives was killed in a US strike on a Haqqani Network compound that same year. That al-Zawahiri appears to have moved relatively recently to Kabul, courtesy his Haqqani Network hosts, raises the question of whether the Pakistan army patrons of that terror group also knew of his whereabouts. One would be shocked if they didn’t.

But what does appear clear is that speculation about a quid pro quo notwithstanding, the US did not seek any cooperation from Pakistan in taking out one of its most wanted foes. The US possibly used an air corridor over Pakistan for over-the-horizon drone action but is unlikely to have informed Islamabad of the mission lest the target is tipped off in advance. The details of the operation will eventually emerge but what is certain now is that the Taliban has been lying through its teeth to the world. What is worse is that Pakistan is acting as the self-proclaimed Emirate’s chief apologist and advocate, trying to convince the world to formally recognise the brutal, lying Taliban machine as the legitimate government of Afghanistan. According to a Taliban spokesman, in a recent meeting with his Taliban counterpart, Pakistan’s ostensibly progressive foreign minister Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari had apparently lauded the Emirate for “ensuring security in Afghanistan and called this an important step towards building trust with the world.” With al-Zawahiri’s elimination, that trust gap is bound to widen, not just with the Taliban but with its Pakistani patrons as well.

Taliban fighters drive a car on a street following the killing of Al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in a U.S. strike over the weekend, in Kabul, Afghanistan, August 2, 2022. Photo: Reuters/Ali Khara

US President Joe Biden has claimed the successful drone strike as a validation of his counterterrorism strategy after the humiliating US withdrawal from Afghanistan. But while it was a tactical success at many levels – including top-notch human intelligence on the ground and a confirmation of America's massive military reach – the attack also raises concerns about the strategic viability of Biden’s total withdrawal decision.

The instant resurgence and regrouping of al-Qaeda in Afghanistan after the Taliban takeover and an active Islamic State in Khurasan (ISIK) show that without continued observation and engagement, a lesser profile terrorist leader with another deadly plot up his sleeve could potentially be difficult to track and neutralize. This could be especially worrying when the new al-Qaeda leader takes over and tries to make his mark with another heinous attack. The aforementioned UN report has also listed potential successors to al-Zawahiri, of whom Sayf al-Adl is senior-most.

In the short term, al-Zawahiri’s assassination is likely to boost al-Qaeda’s propaganda and recruitment efforts. It will also reestablish its preeminence as the leading global jihadist outfit, elbowing out competitors like ISIS. But its ability to become the menacing threat that it once was has definitely been delivered another severe blow.

Mohammad Taqi is a Pakistani-American columnist. He tweets at @mazdaki.

This article went live on August third, two thousand twenty two, at forty-five minutes past eight in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.