Donald Rumsfeld: Upwardly Absorption into the Imperial Hubris of the American Foreign Policy Circle

Donald H. Rumsfeld’s character and career, as depicted in historical records and refracted through William Cooper’s highly readable, well researched, but fictionalised account, The Trial of Donald H. Rumsfeld: A Novel (2025), reveal a man whose ambition, arrogance, and ruthless pragmatism were shaped by the imperial hubris of the American foreign policy establishment.

Rising from middle-class Chicago roots to a towering figure in Washington, Rumsfeld’s alignment with the establishment’s unquestioned belief in US global dominance, unilateral action, and moral exceptionalism (actually ‘exemptionalism’) was a complex interplay of deliberate choices and systemic absorption. His personal traits – arrogance, control, and disdain for dissent – meshed with the establishment’s imperial mindset, something he consciously crafted and absorbed to ascend the power structure.

Rumsfeld is emblematic of the mindsets of the American foreign policy establishment. Cooper’s novel serves as an exciting, accessible way into the world of the masters- of-the-universe attitudes of the elites at the apex of the American imperium.

Weakness is provocative

Donald Rumsfeld’s motto, “Weakness is provocative,” encapsulates a core belief that shaped his approach to US foreign policy and military strategy, reflecting a broader mindset within the American establishment that prioritises strength, dominance, and pre-emption and, more seriously, preventive war.

This phrase, often attributed to Rumsfeld during his tenure as secretary of defence (1975–1977 and 2001–2006), became a leitmotif for a militarised worldview that resonated with establishment insiders, particularly neoconservatives and hawkish policymakers. It reflects a warlike, militarised mindset that made Rumsfeld attractive to the American empire’s national security managers.

“Weakness is provocative” suggests that perceived vulnerability in a nation’s posture – diplomatic, military, or economic – invites aggression from adversaries. For Rumsfeld, this justified a proactive, muscular (lethal, indiscriminately violent) foreign policy to deter threats before they materialise.

It aligns with a realist and neoconservative worldview that emphasises power projection, military superiority, and the prevention of any rival’s ascendancy. The motto implies that peace is maintained not through diplomacy or restraint but through overwhelming strength and readiness to act decisively. There is more than an echo of this mindset in the current Republicam administration.

It aligns with a realist and neoconservative worldview that emphasises power projection, military superiority, and the prevention of any rival’s ascendancy. The motto implies that peace is maintained not through diplomacy or restraint but through overwhelming strength and readiness to act decisively. There is more than an echo of this mindset in the current Republicam administration.

This philosophy underpinned key decisions during Rumsfeld’s second stint as defense secretary under George W. Bush, including the invasions of Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003). It framed military action as a necessary response to potential threats, even absent concrete evidence, as seen in Rumsfeld’s famous “known unknowns” rationale for pre-emptive war.

The motto reflects a belief that hesitation or restraint signals weakness, emboldening enemies, and thus necessitates constant readiness and interventionism. Rumsfeld’s motto is emblematic of a broader American empire mindset that equates security with global military dominance. This perspective, rooted in the post-World War II era and amplified during the Cold War, became especially pronounced after 9/11.

The 2002 National Security Strategy, heavily influenced by Rumsfeld and other neoconservatives, codified this approach, arguing that the US must act against “emerging threats before they are fully formed.” The Iraq War, launched on the premise of eliminating Saddam Hussein’s supposed weapons of mass destruction, exemplified this, despite intelligence to the contrary, scepticism from the US military, and international opposition.

This militarised mindset framed war not just as a tool of last resort but as a proactive means to shape the global order. Rumsfeld’s motto and mindset made him a compelling figure to establishment insiders – politicians, military-industrial complex leaders, and neoconservative intellectuals – because it aligned with imperial ambitions and appealed to military contractors hungry for war contracts.

Character foundations: Ambition and arrogance

Born in 1932 to a realtor father and homemaker mother in Chicago’s North Shore, Rumsfeld’s middle-class upbringing instilled discipline and drive, evident in his wrestling championships, Eagle Scout badge, and Princeton scholarship.

These traits – grit, self-assurance, and a knack for outworking opponents – propelled him into elite circles, from Navy service to a congressional seat at 30 and corporate boardrooms. Cooper’s novel portrays “Rummy” as a charismatic operator, his folksy charm masking a calculating mind. His “Rumsfeld Rules,” maxims like “Don’t let the lawyers decide policy,” reflect a personal code prioritising control and results over bureaucracy, a mindset that resonated with the establishment’s demand for decisive leaders. Yet, this confidence tipped into arrogance and narcissism – a belief that his logic could master any challenge, from wars to interrogations.

His 2003 memo approving torture techniques like waterboarding, with a handwritten note questioning why detainees couldn’t stand for eight hours (“I stand for 8-10 hours a day”), reveals a man whose narrow-mindedness blinded him to human costs, mirroring the establishment’s faith that American will could reshape the world.

Deliberate cultivation or systemic absorption?

Did Rumsfeld deliberately hone his mindset, or did he absorb it to climb the ranks of the American empire’s inner sanctum? The answer lies in a blend of agency, adaptation and absorption.

As a young congressman in the 1960s, he backed anti-communist policies, chiming with the Cold War establishment’s view of America as the free world’s bulwark. His Nixon-era roles – running the Office of Economic Opportunity, serving as NATO ambassador – taught him to navigate power through ruthless pragmatism – streamlining agencies, outmanoeuvring rivals like Kissinger, and mastering media spin. By the Ford administration, as defence secretary alongside Dick Cheney, he deliberately embraced a hawkish stance, sidelining détente for a muscular anti-Soviet agenda, a choice that positioned him as a champion of American supremacy.

Also read: 'Tech Issues Will Continue to Strain Beijing–Washington Ties,' Warns Chinese Foreign Policy Expert

Yet, the establishment’s structure shaped him as much as he shaped it. After World War II, the US foreign policy elite – rooted in institutions like the Pentagon, think tanks like RAND, and networks like the Council on Foreign Relations – demanded leaders who internalised its ethos: America as global hegemon, its values universal, its enemies existential.

Rumsfeld, moving through Princeton, corporate boards (Searle’s CEO), and neoconservative circles, absorbed this as a prerequisite for ascent. His 1980s corporate stint honed a CEO’s mentality – decisive, dismissive of dissent – that aligned with the Pentagon’s top-down culture.

Cooper’s novel fictionalises this, portraying Rumsfeld as a man who “drank the Potomac’s elixir,” but real-world evidence, like his “snowflakes” (terse memos micromanaging the DoD), shows a leader who internalised the system’s demand for control while amplifying it with personal zeal.

Imperial hubris in action: The Bush era

Rumsfeld’s second defense secretary tenure (2001–2006) under George W. Bush crystallised his alignment with imperial hubris. The establishment’s post-9/11 mindset – preventive war, unilateralism, and a belief in America’s unchallenged might – found its champion in Rumsfeld’s push for the Iraq War and “Global War on Terror.”

His “transformation” agenda, emphasising lean, high-tech forces, assumed US superiority could subdue nations with minimal boots on the ground. The 2002 Torture Memos, enabled by his DoD, codified “enhanced interrogation” techniques, a conviction that American ends justified any means. Cooper’s novel depicts this, with Rumsfeld’s fictional presidency escalating torture and drone strikes, believing US power could remake Baghdad. His actual dismissal of Iraq’s looting (“Stuff happens”) and Abu Ghraib as “bad apples” betrayed a refusal to question U.S. moral authority, emblematic of imperial arrogance.

The cost: Personal and systemic failures

Rumsfeld’s arrogance – his belief he could micromanage wars like a corporate turnaround – fuelled catastrophic failures. Trillions of dollars were spent on the war, hundreds of thousands killed and displaced, a state was destroyed, and cultural artefacts looted. The effects reverberate in the region to this day. Would there have been an ISIS had it not been for the Iraq War?

Rumsfeld’s imperial hubris was a symbiotic blend of character and system. His ambition and arrogance, rooted in middle-class hunger for status, made him a natural fit for the establishment’s game, but he deliberately honed his alignment – choosing neoconservative allies, championing pre-emption, and wielding power with CEO-like certainty. Yet, the system’s incentives – rewarding boldness, punishing doubt—moulded him, amplifying and exploiting his flaws.

Also read: 100 US Local Leaders Will Attend COP30 in 'Show of Force'

Cooper’s novel, blending fact and fiction, casts him as a tragic figure, a man whose drive made him the perfect vessel for imperial power grabs. His legacy – Guantánamo’s persistence, Iraq’s scars – warns of the costs when personal arrogance and imperial hubris entwine, a cautionary tale for a 2025 world grappling with America’s fading unipolarity.

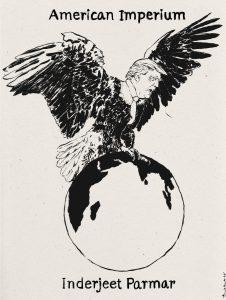

Inderjeet Parmar is a professor of international politics and associate dean of research in the School of Policy and Global Affairs at City St George’s, University of London, a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences, and writes the American Imperium column at The Wire. He is an International Fellow at the ROADS Initiative think tank, Islamabad, on the board of the Miami Institute for the Social Sciences, USA, and on the advisory board of INCT-INEU, Brazil. Author of several books including Foundations of the American Century, he is currently writing a book on the history, politics, and crises of the US foreign policy establishment.

This article went live on November first, two thousand twenty five, at eighteen minutes past two in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.