At this stage it seems reasonable to wonder whether Syria was attacked by the United States and its allies because it didn’t use chemical weapons rather than because it did. That may seem strange until we remember rather weighty suspicions surrounding the main accusers, especially the White Helmets with their long-standing links to the US government.

A second, irreverent puzzle is whether the dominant motive for the attack was not about what was happening in Syria but rather what was not happening in the domestic politics of the attacking countries. Every student of world politics knows that when the leadership of strong states feel stressed and at a loss, they look outside their borders for enemies to slay, counting on transcendent feelings of national pride and patriotic unity associated with international displays of military prowess to distract the discontented folks at home, at least for awhile. All three leaders of the attacking coalition were beset by such domestic discontent in rather severe forms, seizing the occasion for a cheap shot at Syria at the expense of international law and the UN, just to strike a responsive populist chord with their own citizenry and, above all, to show the world that the West remains willing and able to strike violently at Islamic countries without fearing retaliation.

Of course, this last point requires clarification, and some qualification to explain the strictly limited nature of the military strike. Although the attackers wanted to claim the high moral ground as defenders of civilised behaviour in war – itself an oxymoron – they wanted to avoid any escalation with its risks of a dangerous military encounter with Russia. As pro-interventionists have angrily pointed out, the attack was more a gesture than a credible effort to influence the future behaviour of the Bashar al-Assad government. As such, it strengthens the position of those who interpret the attack as more about domestic crises of legitimacy unfolding in the now illiberal democracies of the United States, UK, and France than about any reshaping of the Syrian ordeal.

And if that is not enough to ponder, consider that Iraq was savagely attacked in 2003 by a US/UK coalition under similar circumstances, that is, without either an international law justification or authorisation by the UN Security Council, the only two ways that international force can be lawfully employed, and even then only as a last resort after sanctions and diplomatic measures have been tried and failed. It turned out that the political rationale for recourse to aggressive war against Iraq – its alleged possession of weapons of mass destruction – was totally false, either elaborately fabricated evidence or more generously, a hugely embarrassing intelligence lapse.

To be fair, this Syrian military caper could have turned out far worse. The entire attack lasted only three minutes, no civilian casualties have been reported, and thankfully, there was no challenge posed to the Russian and Iranian military presence in Syria, or to the Syrian government, thus avoiding the rightly feared retaliation and escalation cycle. More than at any time since the end of the Cold War sober concern abounded that a clash of political wills or an accidental targeting mistake could cause geopolitical stumbles culminating in World War III.

No evidence or rationale

Historically minded observers saw alarming parallels with the confusions and exaggerated responses that led directly to the prolonged horror of World War I. The relevant restraint of the April 14 missile attacks seems to be the work of the Pentagon, and certainly not the White House. Military planners designed the attack to minimise the risks of escalation, and possibly an undisclosed negotiated understanding with the Russians. In effect, Trump’s red line on chemical weapons was supposedly defended, and redrawn at the UN as a warning to Damascus.

Yet can we be sure at this stage that the authors of this aggressive move had accurately portrayed Syria as having launched a lethal chlorine attack on the people of Douma? Certainly not now. We have been fooled too often in the past by the confident claims of the intelligence services working for the same countries that sent missiles to Syria. There is a feeling of a rush to judgment amid some strident, yet credible, voices of doubt, including from UN sources. The most cynical are suggesting that the real purpose of the attack, other than Trump’s red line, is to destroy evidence that would incriminate others than the Syrian government. Further suspicions are fuelled by its timing, which seems hastened to make sure that the respected Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) – which is about to start its fact finding mission into the Douma incident – would have nothing to find.

To those who believe these are ideologically driven worries, it is notable that the Wall Street Journal, never a voice for peace and moderation, took the view that it was not “clear who carried out the attack” on Douma – a view shared by several mainstream media outlets including the Associated Press. Blaming Syria, much less attacking it, is clearly premature, and, quite possibly, altogether false – undermining the factual basis of the coalition claim without even reaching the piles of doubts associated with unlawfulness and illegitimacy.

Less noticed, but starkly relevant, is the intriguing reality that the identity of the three states responsible for this aggressive act share strong colonialist credentials that expose the deep roots of the turmoil afflicting the entire Middle East in different ways. It is relevant to recall that it was British and French colonial ambitions in 1917 that carved up the collapsed Ottoman Empire, imposing artificial political communities with borders reflecting European priorities not natural affinities, and taking no account of the preferences of the resident population. This colonial plot foiled Woodrow Wilson’s more positive proposal to implement self-determination based on the affinities of ethnicity, tradition and religion of those formerly living under Ottoman rule. The United States openly supplanted this colonial duopoly rather late, as the Europeans faltered in the 1956 Suez Crisis, but made a heavy footprint throughout the region with an updated imperial agenda of Soviet containment, oil geopolitics, and untethered support for Islam. These priorities were later supplemented by worries over the spread of Islam and of nuclear weaponry falling into the wrong political hands. As a result of a century of exploitation and betrayal by the West, it should come as no surprise that anti-Western extremist movements emerged throughout the Arab World in response.

From Kosovo to Iraq, Libya and Syria

It is also helpful to recall the Kosovo War (1999) and the Libyan War (2011), both of which were managed as NATO operations and carried out in defiance of international law and the UN Charter. Because of an anticipated Russian veto, NATO, with strong regional backing, launched a punishing air attack that drove Serbia out of Kosovo. Despite a strong case for humanitarian intervention, it set a dangerous precedent, which the Iraq hawks in the Bush administration found convenient a few years later. In effect, the US was absurdly insisting that the veto should be respected only when the West uses it – say, to protect Israel from much more trivial, yet justifiable, assaults on its sovereignty than what a missile attack on Syria signifies.

The Libyan precedent is also relevant to the marginalisation of the UN and international law to which this latest Syrian action is a grim addition. Because the people of the Libyan city of Benghazi truly faced an imminent humanitarian emergency, the UN case for lending protection seemed strong. Russia and China, permanent members of the UNSC, temporarily suspended their suspicions about Western motives and abstained from a resolution authorising a No Fly Zone. They were quickly shocked into the realisation that real NATO mission in Libya was regime change, not humanitarian relief. In other words, these Western powers who are currently claiming at the UN that international law is on their side with regard to Syria, have themselves a terrible record of flouting UN authority when convenient and insisting on their full panoply of obstructive rights under the Charter when Israel’s wrongdoing is under review.

Power beyond the veto

Ambassador Nikki Haley, the Trump flamethrower at the UN, arrogantly reminded members of the Security Council that the US would carry out a military strike against Syria whether or not permitted by the organisation. In effect, even the veto as a shield is not sufficient to quench Washington’s geopolitical thirst. It also claims the disruptive option of a sword to circumvent the veto when blocked by the veto of an adversary. Such a pattern puts the world back to square one when it comes to restraining the international use of force. Imagine the indignation that the US would muster if Russia or China proposed at the Security Council a long overdue peacekeeping – a ‘responsibility to protect’ – mission to keep safe the abused population of Gaza. And if these countries then had the geopolitical gall to act outside the UN, the world would almost certainly experience the bitter taste of apocalyptic warfare.

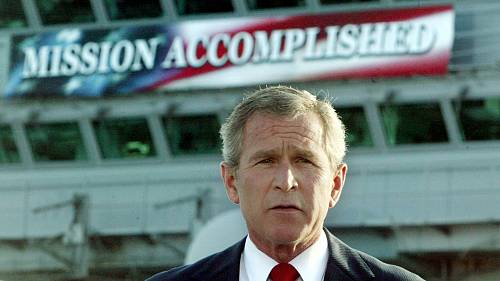

Bush announced the ened of the Iraq war in April 2003 with a banner in the background proclaiming, ‘Mission Accomplished’. Fifteen years later, that mission remains incomplete. Credit: Reuters

The UN Charter framework makes as much sense, or more, than when it was first crafted in 1945. Recourse to force is only permissible as an act of self-defence against a prior armed attack, and then only until the Security Council has time to act. In non-defensive situations, such as the Syrian case, the Charter makes clear beyond reasonable doubt that the Security Council alone possesses the authority to mandate the use of force, including in response to an ongoing humanitarian emergency. The breakthrough idea in the Charter is to limit as much as language can, discretion by states to decide on their own when to make war. Syria is the latest indication that this hopeful idea has been crudely cast in the wastebasket of geopolitics.

It will be up to the multitudes to challenge these developments, and use their mobilised influence to reverse the decline of international law and the authority of the UN. The members of the UN are themselves so beholden to the realist premises of the system that they do no more than squawk from time to time. Trump ending his boastful tweet with the words ‘mission accomplished’ unwittingly reminds us of the time in 2003 when the same phrase was on a banner behind George W. Bush as he spoke of victory in Iraq from the deck of an aircraft carrier with the sun setting behind him. Those words soon came back to haunt Bush, and if Trump were capable of irony, he might have realised that he is likely to endure an even more humbling fate.

Richard Falk is Professor Emeritus of International Law at Princeton University.

Note: The piece was edited at 8 pm IST on April 15 to add the second and third paragraphs.