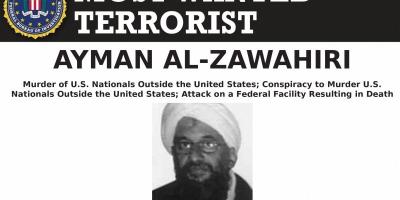

Late on Sunday night, President Joe Biden informed the American people on national television that a CIA drone strike had killed Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri at his home in Kabul. He recalled al-Zawahiri’s “trail of murder and violence” against American citizens and then solemnly pronounced: “Now, justice has been delivered. And this terrorist leader is no more.”

The president also provided some operational details. He said that US intelligence had, earlier this year, tracked the Al-Qaeda leader to his home in the suburbs of Kabul, repeatedly confirmed his identity, and tested the planned attack on models of his home to minimise casualties. After being convinced of al-Zawahiri’s identity, the president said he had ordered a precision strike to “remove him from the battlefield once and for all”. A week ago, he had given the final approval to “go get him”.

The president said resoundingly that “we will never again, never again allow Afghanistan to become a terrorist safe haven [or] a launching pad against the United States”. Biden of course failed to recall that it was the United States which, in partnership with Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, had consciously and deliberately converted the Afghan national struggle against Soviet occupation into a “global jihad”.

That state-sponsored faith-based project drew Muslim youth from almost all Islamic countries and communities globally, delivering, at its peak, over 100,000 militants at the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. These militants were indoctrinated in extremist Islam, trained in war and subversion, and then, as the Soviet troops withdrew in defeat in 1989, rewarded with a glorious victory for their God and faith.

Domestic fallout

Saudi Arabia, Biden’s new-found friend in West Asia, and the US’s enthusiastic partner in the ‘global jihad’, has welcomed the killing. Its official statement has described al-Zawahiri as “one of the leaders of terrorism” who had planned and executed several “heinous terrorist operations” in the US, Saudi Arabia and several other countries.

The kingdom, too, failed to mention its substantial role in organising and funding Al-Qaeda, providing the ideological bases for the struggle, identifying the leadership and supplying weapons for the jihad, and encouraging the large cohorts of brain-washed youth to join its cadres in the battlefields of Afghanistan. Instead, Saudi Arabia called for “strengthening cooperation and concerted international efforts to combat and eradicate terrorism”, in short, the very scourge that it had itself created.

While making his announcement, Biden was also trying to serve an urgent domestic agenda. As the New York Times has pointed out, al-Zawahiri’s death is “a major victory for Mr Biden at a time of domestic political trouble”. Over the last several weeks, the president has exposed himself with repeated gaffes and so diminished his standing as to raise doubts about his fitness for national leadership, while portending serious setbacks for the Democrats in the mid-term polls in November. This would lead to a lame-duck presidency and even raise concerns about a Democratic victory in the next presidential polls.

Hence, not surprisingly, Biden used al-Zawahiri’s killing to justify the ignominious withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan in August last year. The president said that he had ordered the withdrawal as the US “no longer needed thousands of boots on the ground”, but had also assured his people that counter-terrorism operations would continue to be conducted “in Afghanistan and beyond”; now, with al-Zawahiri’s assassination, “We’ve done just that”, Biden said.

Osama bin Laden sits with his adviser Ayman al-Zawahiri, an Egyptian linked to the al Qaeda network, during an interview with Pakistani journalist Hamid Mir (not pictured) in an image supplied by Dawn newspaper November 10, 2001. Hamid Mir/Editor/Ausaf Newspaper for Daily Dawn/Handout via Reuters.

However, America’s polarised politics has not allowed the president to savour the moment. The ranking Republican in the Senate Armed Forces Committee has asserted that al-Zawahiri’s presence in Afghanistan in fact “reflects the total failure of the Biden administration’s policy towards that country”. His counterpart in the House Foreign Affairs Committee has said that the killing in Afghanistan is a reminder that “the American people were lied to by President Biden. Al-Qaeda is not gone from Afghanistan as Biden had claimed a year ago”.

Al-Zawahiri: the shaping of the radical

Ayman al-Zawahiri was born in 1951 into an Egyptian family that was distinguished for its learning – his paternal grandfather was an Islamic scholar and Imam of the Al-Azhar University, the most important seat of learning of Sunni Islam, while his maternal grandfather was a scholar of literature, president of Cairo University, and the Egyptian ambassador to Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Yemen. His uncle, Abdul Razzak Azzam, was the first secretary general of the Arab League.

Also read: Al-Qaeda After Al-Zawahiri

His biographer, Muntassir al-Zayat, has suggested that the trauma of the Arab defeat in the 1967 war led al-Zawahiri at a young age to seek solace – and an understanding of the debacle Islam faced – in the writings of the radical Egyptian intellectual, Sayyid Qutb. Well before the war, Qutb had described contemporary Muslim societies as living in jahilliyya, the age of ignorance that was redolent of the period before the advent of Islam. Qutb had then called for the total reform of Muslim polities on the basis of pristine Islamic norms, values and practices.

Al-Zayat says that al-Zawahiri was also influenced by the writings of the 13th-century Islamic scholar, Ibn Taymiyyah, who had spoken of a compact between the pious ruler and the Muslim community, with the latter only owing loyalty to the ruler if he was just and followed the tenets of Shariah. He had also insisted on the acceptance of only those rulers who were truly Islamic, thus sanctioning rebellion against recalcitrant rulers.

Taliban fighters drive a car on a street following the killing of Al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in a U.S. strike over the weekend, in Kabul, Afghanistan, August 2, 2022. Photo: Reuters/Ali Khara

Al-Zawahiri is also said to have been deeply affected by President Nasser’s harsh crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood in 1965-66, which included the execution of Sayyid Qutb in 1966. He viewed this as a war on Islam that needed to be resisted – he pursued this through the Tanzeem (‘The Organisation’) he set up in 1966-67, that was aimed at overthrowing Nasser’s government and replacing it with an Islamic order. The Tanzeem mutated into Tanzeem al-Jihad and later the Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ) that al-Zawahiri came to control from 1975.

Despite his political activism, al-Zawahiri pursued medical studies till 1974, and then specialised in ophthalmology for another four years.

After the assassination of Anwar Sadat in 1981, al-Zawahiri was among hundreds of suspects arrested and subjected to harsh torture. He was released in 1984, after serving a three-year sentence.

Jihadi ideology

Al-Zawahiri made short trips to Afghanistan in 1980, 1984 and 1986. He believed that, though the principal battle for an Islamic order would be fought in Egypt, the jihadi movement needed an “incubator” where it would grow and acquire practical experience in combat, organisation and politics. He thought that Afghanistan could play this role.

He settled in Peshawar in 1986. In 1987, he met Osama bin Laden, the Saudi national and scion of one of his country’s most distinguished business families, who was managing the ‘global jihad’ – organising the logistics, supplies and personnel who had answered the call of jihad. Al-Zawahiri was inspired by bin Laden’s view of global jihad – the war that was not just against the Soviet Union, but was also directed against the corrupt secular governments of West Asia, the US and Israel.

The coming together of bin Laden and al-Zawahiri created a unique symbiotic relationship that would have significant implications for transnational jihad and world politics in general. Lawrence Wright, the author of The Looming Tower, a seminal study of the 9/11 attacks, says that this relationship “made [them] into people they would never have been individually … and made Al Qaeda the vector of these two forces. … As a result, Al-Qaeda would take a unique path, that of global jihad”.

The most significant outcome of this engagement was the new focus on the “far enemy” – as the biographer al-Zayat has pointed out. While al-Zawahiri converted bin Laden from a preacher prioritising relief into a jihadi fighter, bin Laden changed al-Zawahiri’s perspective from one combatting the “near enemy” – the regimes in West Asia – into one confronting the “far enemy”, i.e. the US and Israel.

This new focus led to the attacks on the US embassies in East Africa in August 1998, the attack on the warship, USS Cole, off the coast of Aden, in October 2000, and finally the 9/11 attacks on the US mainland in September 2001.

A photo Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri. Still image taken from a video released on September 12, 2011. Photo: SITE Monitoring Service/Handout via Reuters TV/File

By 1998, Ayman al-Zawahiri had become the principal ideologue of Al-Qaeda, providing the perspectives and justifications from diverse Islamic sources for actions taken by Al-Qaeda. His thinking was “a completely new departure for the Islamist movement”, the scholar Maha Azzam has noted, being based neither on mainstream Muslim theology, nor on Ibn Taymiyya, nor even on the writings of the 18th century Saudi cleric, Sheikh Mohammed ibn Abdul Wahhab.

His first targets were the rulers of various West Asian countries, whom he accused of “diverting the ummah from the creed and preventing by force the practice of the faith”. Their principal allies, he pointed out, were the Jewish and Christian regimes, whose military machine “occupies exalted Jerusalem”, is “within a mere 90 kilometres from the shrine in Mecca”, and whose “Jewish tanks have destroyed homes in Gaza and Jenin [in Palestine]”.

The only response to these challenges was, in his view, jihad; he made the strident call: “Let the Muslim youth not await anyone’s permission – for Jihad against the Americans, Jews, and their alliance of hypocrites and apostates is an individual obligation. … We must set our lands aflame beneath the feet of the raiders; they shall not depart otherwise.”

Defending the 9/11 attacks

The 9/11 attacks not only divided opinion among Islamic movements, but they created differences among radical Islamic groups as well. The spiritual guide of the Hezbollah, Mohammed Hussain Fadlallah, said he was “horrified” by these “barbaric crimes” which were forbidden by Islam. The Sudanese Islamist ideologue, Hassan al-Turabi, described the killing of American civilians as morally wrong and politically harmful. The head of the Islamic Jihad in Egypt said that the attacks violated Islamic law and recalled several occasions when the US had supported Islamic causes.

There were also criticisms from within Al-Qaeda itself. Abul Walid al-Masri, a veteran of the Afghan jihad, criticised bin Laden for his authoritarian approach, the curbing of internal debate, and his fondness for media attention; he described his leadership as “catastrophic”.

Al-Zawahiri help prepare Al-Qaeda’s responses. In April 2002, a formal statement said that the attacks were in accord with Islamic law – the attacks had been defensive measures against the “Zionist-Crusader” plot to annihilate Muslims. Critics were described as “rulers’ sheikhs” who were backing the “Crusaders’ … revenge on Muslims”.

Also read: How Cairo Physician Ayman Al-Zawahiri Came to Be the Leader of Al Qaeda

Al-Zawahiri reserved his sharpest attacks for his former Egyptian colleagues. In December 2001, he published his most important work – Knights Under the Prophet’s Banner. Though started in early 2000, it was completed just after the 9/11 attacks. He called for unity among jihadi groups, taking the fight to the enemy’s home, and the use of extreme violence; this was because the West “does not know the language of ethics, morality and legitimate rights. They only know the language of interests, backed by brute force”.

He condemned his Egyptian critics for changing from “hot-blooded revolutionary strugglers” to “cold as ice” due to their enjoyment of Western material comforts. He urged Muslims to be wary of the enemies of Islam who were carrying out a “misleading intellectual and moral campaign” in support of the military campaign against Al-Qaeda to keep the existing order in place.

After 9/11

Following the destruction of the Taliban-led Emirate of Afghanistan by US military forces in October-November 2001, Al-Qaeda ceased to be the tightly-controlled and centrally-directed organisation it used to be earlier. Al-Qaeda affiliates sprang up in different parts of West Asia and North Africa which were largely autonomous in terms of their operations, though they occasionally sought guidance and approval from bin Laden and al-Zawahiri and operational advice and support from other leaders in different places.

But there were already signs of the diminishing authority of the central leaders. Thus, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, leading the fight against US occupation after the 2003 invasion, under the banner of Al-Qaeda in Iraq, rejected criticisms from bin Laden and al-Zawahiri about his violence against the Shia population. Al-Zarqawi, described by Fawaz Gerges as a “sectarian psychopath”, insisted that his actions were sanctioned by the Shariah. After his death in 2006, his successors rejected their ties with Al-Qaeda and renamed their organisation, the Islamic State of Iraq. In 2012, this became the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and then, in 2014, the Islamic State under the leadership of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

The ideologue of the Islamic State was Turki Al-Bin Ali (1984-2017). Though he was over 30 years younger than al-Zawahiri, he robustly debated the latter’s criticisms in order to justify the actions of the Islamic State. These included al-Baghdadi’s defiance of al-Zawahiri’s instruction to retain the separate identity of Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria and his criticism of the Islamic State’s rampant violence against the Shia.

These differences included personal attacks on al-Zawahiri, leading to the final break between Al-Qaeda and ISIS in February 2014. In April 2014, al-Baghdadi’s spokesperson, Abu Mohammed al-Adnani, said that “Al-Qaeda today is no longer the seat of true jihad … its leaders have deviated from the true path”. This schism between Al-Qaeda and the nascent Islamic State culminated in the latter taking over the leadership of global jihad.

A changed West Asia

Obviously, by the time al-Zawahiri was killed, he was a seriously diminished individual – far removed from bin Laden’s influential second-in-command before and just after the 9/11 attacks. Though learned and highly committed to the jihadi cause, he did not have bin Laden’s charisma and could not steer Al-Qaeda with any degree of success after the US attacks on Afghanistan following 9/11.

Even when bin Laden was alive, Islamic radicals and veterans of the Afghan jihad and the civil conflict of the 1990s – men such as al-Zarqawi – were aggressively questioning bin Laden and al-Zawahiri, a situation that led to the final breakup of transnational jihad after the rise of ISIS.

A general view of Kabul following the killing of Al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in a U.S. strike over the weekend, in Sherpur area, in Kabul, Afghanistan, August 2, 2022. Photo: Reuters/Ali Khara

Al-Zawahiri was also challenged by other Islamist intellectuals, such as Abu Mohammed al-Maqdisi and Abu Qatada al-Falastani, besides the much younger Turki Al Bin Ali. They criticised Al-Qaeda for losing its ideological purity, the two seniors even accusing Al-Qaeda under al-Zawahiri of following in the steps of the Kharijites, a divisive group in early Islam which had rejected the caliphate after Hazrat Ali and defined a Muslim so narrowly as to describe almost all Muslims, other than themselves, as apostate. Turki Al Bin Ali even referred to al-Zawahiri as “the fool who is obeyed”.

‘Justice has been delivered’?

Beyond these disputes among jihadi intellectuals lie two facts on the ground: one, the structures and institutions of transnational jihad – Al-Qaeda and ISIS – have been systematically destroyed with military force and their top leaders eliminated.

Two, West Asia itself has moved well beyond political Islam and today is in search of new ideas to shape its resistance to domestic tyranny and external interventions. After the 9/11 attacks, it was widely observed in the region that the violence justified on the basis of Islamic doctrine by diverse scholars and activists had lost whatever strategic value it might have had in furthering Muslim interests. The reality experienced was just the opposite – strengthening of tyranny at home and increasing “Islamophobia” abroad.

In the first part of the Arab Spring uprisings, it did seem as if political Islam, as represented by the Muslim Brotherhood, would be the effective triumphant force in Arab politics – bringing together the principles of pristine Islam and parliamentary democracy in one political order. The failure of these uprisings to deliver viable state order with popular participation and the systematic curbing of the Brotherhood and its affiliates in different countries by the tyrannies of the Gulf led to a second round of Arab Spring uprisings – in Iraq, Lebanon, Algeria and Sudan – which had no association with political Islam whatsoever.

Obviously, the problem in West Asia of governance with political participation remains – but the bases for resistance are increasingly likely to be found outside Islam.

Thus, the significance of al-Zawahiri’s death lies not in West Asian politics – which has already transcended his baleful influence and legacy – but in the US. Over 20 years after the trauma of the 9/11 attacks, Biden has noted that, with al-Zawahiri’s death, “Justice has been delivered”. Surely, this is a gross exaggeration. From the American perspective, justice had already been delivered with the destruction of the Emirate of Afghanistan in 2001, the attack on Iraq in 2003 (though this had nothing to do with the 9/11 attacks), and finally the killing of bin Laden in 2011.

Al-Zawahiri’s killing is at best a footnote in this paradigm. Thus, what we are left with is a beleaguered president desperately seeking to present himself to his bemused people as a commander who fights terrorism with all the commitment and force at his command, ordering his soldiers to “go for him” efficiently and ruthlessly. So that justice is delivered to the American people.

But there is a call from West Asia for justice as well. The attacks on Afghanistan and the subsequent US occupation of that country caused the deaths of 200,000 Afghans. The US attacks on Iraq and the subsequent occupation took the lives of 400,000 Iraqis. The US assault on Iraq in 2003 had no plausible justification then, and none has been proffered since. And, yet, the war included the precision bombing of an air raid shelter in which hundreds were killed and the horrific abuses of Abu Ghraib. No one has been punished for these crimes.

As Americans celebrate Biden’s ‘delivery of justice’, they should also remember that neither he nor his predecessors have ever introspected about the US’s own complicity in encouraging global jihad. Unless the underlying problem is addressed, Americans will not be safe from blowback by future warriors spawned by US policies.

Talmiz Ahmad, a former ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Oman and the UAE, holds the Ram Sathe Chair for International Studies, Symbiosis International University, Pune, and is Consulting Editor, The Wire.