When Cartoonists Are Censored, We All Need To Be Concerned

The purpose of political cartoons is to prick pomposity and cut those who rule over us – or aspire to – down to size. India, the US and the UK all have rich traditions of cartooning and caricatures. It’s a hallmark of a robust democracy that people in power, whether in government or the corporate world, just have to put up with the discomfort of being mocked by the cartoonist’s pen.

When cartoons get censored, it’s often an indication that democracy is falling into disrepair. That’s why the stand taken by one of America’s top cartoonists matters. Ann Telnaes, an editorial cartoonist with the heavyweight Washington Post since 2008, has announced that she’s quitting because her paper has refused to carry one of her drawings. "I’ve never had a cartoon killed because of who or what I chose to aim my pen at," she said. "Until now."

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

She’s released a rough draft of the cartoon that her paper has refused to publish. A group of tech and media barons are shown bringing financial tribute to a statue of President-elect Donald Trump. And Mickey Mouse, the corporate mascot of Disney (which now controls ABC and other TV networks), is depicted prostrating himself at the feet of the new leader. On the left of the group is the easily identifiable bald head of Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, and also, perhaps more relevantly, the owner of the Washington Post.

Some might argue it is unreasonable for a cartoonist to make fun of the proprietor of the paper that pays their salary. Others would say that the cartoon is fair comment. Big tech entrepreneurs and media company heads have bent the knee to the new president. Several have donated large amounts to Trump’s inauguration fund; tamped down previous critical comments; or in the case of Bezos’s notably liberal daily paper, abandoned a longstanding tradition of endorsing the Democrat candidate in presidential elections.

Telnaes, who has won a prestigious Pulitzer prize for her political cartooning, has stated of the spiking of her drawing: "There have been instances where sketches have been rejected or revisions requested [by editors], but never because of the point of view inherent in the cartoon’s commentary. That’s a game changer… and dangerous for a free press."

The opinions editor of the Washington Post insisted that the cartoon wasn’t published simply because it covered an issue already recently featured in the paper. "Not every editorial judgment is a reflection of a malign force," David Shipley said in a statement. ‘The only bias was against repetition.’

Cartooning traditions in India and the UK

Cartooning and political caricatures developed in England more than 200 years ago. Although many imagine that to be a more deferential era, some of the squibs were more vulgar and cruel than anything that would appear in the mainstream media today. The Prince Regent, who later ascended to the throne as King George IV, was often depicted guzzling, farting, pissing and fornicating.

In Britain, controversy about cartooning in recent years has been about the depiction of religious or racial stereotypes. In 2023, the left-of-centre Guardian newspaper took down from its website and apologised for publishing a cartoon of a public figure – a departing chair of the BBC – which resorted to stereotypically antisemitic imagery.

Martin Rowson, the cartoonist concerned, accepted he had made an error. He later shared his personal guidelines for political cartoons, which many of his craft around the world would probably endorse. "I should never attack anyone less powerful than me. I should never attack people for what they are – their ethnicity, gender or sexuality – only for what they think and do. And should I ever offend anyone I hadn’t targeted, I would always apologise."

India’s rich history of cartooning – from R.K. Laxman to Sudhir Dar – is second to none. I have cartoons by masters like Ajit Ninan and Sudhir Tailang on the walls of my London home. Among Indian cartoonists, Kerala’s Abu Abraham was exceptional in unpacking the import of global as well as national news stories through his remarkable craft skills and political acumen.

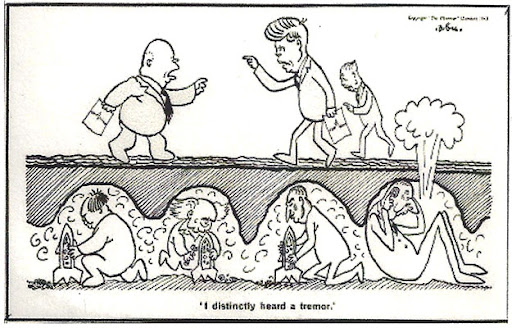

Abu Abraham's 1963 cartoon on the nuclear arms race during the Cold War. Published with kind permission of Ayisha Abraham.

Abraham spent a decade as staff political cartoonist at the Observer in London. The cartoon reproduced here from 1963 reflects the perils of the nuclear arms race during the acute tension of the Cold War. The Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and America’s youthful President John F. Kennedy (followed, puppy dog-like, by British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan) are shown in confrontational mode, while hidden from view, the Chinese, the French and assorted scientific boffins are quietly testing their own nuclear devices.

On returning to India, Abraham spent 12 years with the Indian Express – a period which covered Indira Gandhi’s Emergency and the censorship that came with it. Once normal democratic governance resumed, he released a book of all the articles and cartoons he had been unable to publish because of Emergency restrictions.

The freedom to hold public figures accountable through cartoons is a measure of a healthy political system. "Over the years I have watched my overseas colleagues risk their livelihoods and sometimes even their lives to expose injustices and hold their countries’ leaders accountable," Telnaes said while announcing her resignation. "I believe that editorial cartoonists are vital for civic debate and have an essential role in journalism."

When prominent cartoonists are told that some public figures are off limits for their satire, we all need to be concerned.

Andrew Whitehead is a former BBC India correspondent.

London Calling: How does India look from afar? Looming world power or dysfunctional democracy? And what’s happening in Britain, and the West, that India needs to know about and perhaps learn from? This fortnightly column helps forge the connections so essential in our globalising world.

This article went live on January sixth, two thousand twenty five, at thirty minutes past one in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.