‘In Honour of William Shakespeare’: Tagore in the Garden of Shakespeare's Birthplace

Within 15 days of William Shakespeare's birthday, April 23, Bengalese, in particular, celebrate the birthday of their undisputed icon – Rabindranath Tagore – with pomp and show. Shakespeare Day and Rabindra Jayanti are two back-to-back cultural events in Bengal’s academia and higher education institutes especially. Right from organising seminars and conferences to hosting performances and screenings, the preparations for the two events make the humid weather of April-May bearable.

Though the icons have centuries between them, their influence over Bengal in general and Bengal’s academia in particular has been unquestionable. A student of literature would inevitably study the two, and anyone interested in literary pursuits would mandatorily turn the pages of both, at least once in life, if not more often.

Born as a Bengali and with Tagore in my mind and spirit, I had no plan of studying English literature for higher studies while at school. In my typical middle-class Bengali household, Rabi Thakur, as he is fondly referred to, was my constant companion. From Rabindra Rachanabalis stacked in my father's brown almirah to the huge piles of Rabindra Sangeet cassettes stored in my mother’s shelf, the white beard and the loose gown was an absent presence in our house.

When I started to move my limbs in rhythm, a Rabindranath nritya expert came down from neighbouring Santiniketan, the abode of peace, every Sunday to teach me the niceties of the art.

Back then, Puja pandals, during cultural meet-ups, always preferred Rabindra Sangeet more than Adhunik, or contemporary songs. No one asked me to recite Shakespeare's sonnets, even though I could, during any recitation competitions; despite the overarching presence of Sukanta Bhattacharya, Kazi Nazrul Islam and Sukumar Ray, Rabindranath always had the upper hand. In fact, during my childhood, Rabindra Sangeet was everywhere, except for traffic signals.

So, before I could scratch my head with the eternal dilemma – ‘to be or not to be’ – I found myself in a garland-wrapped wrist, in a yellow saree and a bun, swaying from one end of the stage to the other in my convent school, while Rabindranath’s songs, such as Amar mukti aloy aloy or Momo chitte niti nitte, played in the background. Rabindranath, effortlessly, resided within me.

As I grew up a little and began to hunt down forbidden spaces of my father's study, I discovered an oval-shaped photo of a semi-bald man with a black moustache and sharp-eye called William Shakespeare. From the glass slides of the almirah, King Lear, Macbeth, As you Like It etc invited me towards a strange land. Sometimes I used to take out a book, read a few lines and, then deeply uninterested, keep it back.

But whenever Rabi Thakur's tune played from the loudspeaker outside my house, or from my mother’s transistor, my heart danced like a peacock, spreading its wings far and wide. Clearly Rabindranath won the first set of my life-tennis.

Also read: Remembering Two Unusual Encounters with Tagore, Bookended By War

Adolescence brought Shakespeare on the crease. Yet to read Chitrangada, the Romantic comedies of Shakespeare gave me an access to feelings hitherto unknown. I began to sing, dance and act Shakespeare on stage. Our English teacher mesmerised us with explanations of the lines which had once appeared illegible to a growing kid. School concerts helped me appreciate the craftsman called Shakespeare. Now in my cultural vocabulary, Premer joware, bhashale dohare and ‘Spring time, ring time’ could exist happily together.

During my board exams, I scratched my English answer sheets with as many lines from Shakespeare as possible! In my Bengali exam, Rabindranath took the lead. I never realised how the two were unconsciously shaping me for a twining future!

After convent schooling, my life took a U-turn. I distinctly remember a day in a Bengali-medium college of a small mofussil town; we were singing a song by Tagore – Sonkochero biholotay hoyeo na mriyoman – when suddenly a bespectacled teacher entered the class and started to shout: ‘Put out the light’, ‘Put out the light’.

Within a second, he looked at me and asked the most difficult question: ‘Hey, you, tell me who said this and where?’ Dumbstruck, I couldn't answer. I heard the choicest expletives that day, which made me determined to study all the Shakespearean plays so that no one could ever dare to behave with me like that. My teacher had criticised me in front of the whole class because I had not studied Othello in class 11. Even Rabindranath's songs couldn't save me from his wrath.

I hunted down Shakespeare with a grudge that made me fall in love with Shakespeare studies. Well, a commerce student ended up studying English literature after class 12 simply because she wanted to explore Shakespeare more! From the alleys of economics and accountancy, Shakespeare drowned me into an ocean of unknown treasures, only to surface with riches.

Needless to say, Shakespeare was and is still, deservingly so, the most talked about subject in English classrooms in West Bengal. Not a single university curriculum in the state can get rid of him. In fact, West Bengal has produced the greatest scholars of Shakespeare. The interesting thing is, a similar trajectory is followed in the case of Rabindranath studies. Can anyone think of a Bengali curriculum without Rabindranath? Not in the near future, at least.

My red-earthed university helped me to appreciate literature on a comparative basis. From English literature to literatures written in English, I found the curriculum holistic – allowing me to study Shakespeare and Rabindranath simultaneously. There was a joy in discovering overlapping territories.

As I became a teacher of English literature, I often escaped into the gamut of Bengali literature while teaching a poem or a play or a novel in English. In this practice, Rabindranath and Shakespeare became a permanent presence in my classes.

The second set of life-tennis, therefore, concluded in a draw, with both the artists serving at their best.

Rabindranath practically evaporated from my mind during my visit to Shakespeare's birthplace in Stratford-upon-Avon. Photo: Kev747/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0.

In the eighteenth year of my teaching career, I finally managed to land up at his village: Stratford-Upon-Avon. My heart and soul, by that time, had been auctioned to the memory of Shakespeare. No one, not even Rabindranath, could claim an acre of grass in my psyche, for I have been waiting for long to witness the remnants of his life.

When the moment finally came, and I stepped into the station, I could smell a town that still carried its ancient lineage. Incidentally, the town, which began as a settlement at a ford during Roman and Saxon times, and then became a thriving market town with a famous three-day fair attracting merchants from near and far, has now developed into a bustling tourist place.

Visitors mainly flock to see Shakespeare's birthplace; Anne Hathaway's cottage, where he went to court his would-be-wife; and New Place, where he stayed during his retired life after 1610.

Of all the three houses, I was keen to see his birthplace, located in the centre of the town, in Hanley Street. The house belonged to his well-respected father, John Shakespeare, who was a businessman and a glover and then went on to occupy an important position in the town administration. The house probably also served as the place for his glove-making business and so, half of the house was used as his workshop, while the family stayed in the other half.

Soaked in the ambience of Shakespeare and his time, I roamed about in every nook and corner, often pinching myself to believe that I was finally there!

Rabindranath practically evaporated from my mind.

As I stepped into his birthplace, which is a museum now, I realised that a portion of the house was rebuilt while a portion had been retained. The house had some authentic items and some replicas. Most importantly, his father's glovers’ workshop was authentically recreated.

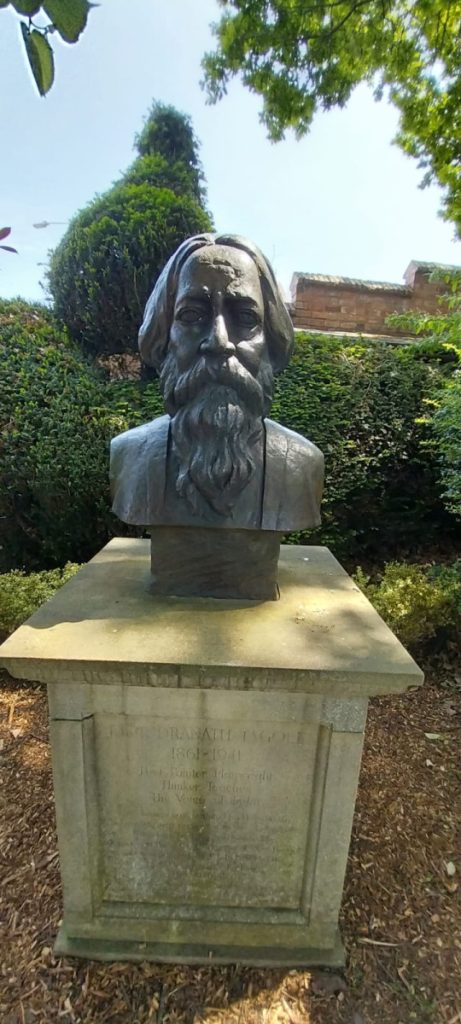

To the front of the property, one could notice a beautiful garden, containing various kinds of plants, herbs and flowers. When I reached his garden and was marvelling upon the same, a familiar bust in bronze seized my attention. In one of the farthest corners of the garden, away from the hustle-bustle of the house, stood Rabindranath's bust, glistening in the rays of the afternoon sun.

I was shocked to find Rabindranath's bust in Shakespeare's birthplace. I had happily forgotten about him and now he had surfaced out of nowhere! I was overwhelmed.

Just then, my eyes fell on some engravings just below the bust. On its body, it was written Rabindranath Tagore - a ‘poet, painter, playwright, thinker, teacher’ and ‘the voice of India’. I began enquiring with the volunteers of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust and was enlightened to know the deep reverence Stratford-upon-Avon has for Rabindranath.

Incidentally, in 1916, Tagore wrote a poem entitled In Honour of William Shakespeare commemorating his 300th death anniversary. In the poem, he praised Shakespeare as both an English poet as well as a poet of the world.

Fakrul Alam in his article entitled “The World’s Bishwa-Kobi” goes back to the origin of the poem:

“Recollecting the occasion that led to the composition of the poem in Shantiniketan in 1921, he noted that he had written it in Shelaidah on 1915 on the occasion of the 300th death anniversary when requested to do so by the Shakespeare Tercentenary committee in Britain. I would like to mention here that Rabindranath had also published a serviceable English prose translation of the poem in English in 1916 that was published by OUP [Oxford University Press], but let me note now that in the poem's opening line he addresses Shakespeare as ‘Bishwa-Kobi’.”

Rabindranath Tagore's bust in the garden outside Shakespeare's birthplace. Photo courtesy of author.

The poems hails Shakespeare as the ‘Sun’, the primary source of creation who has made heaven his territory now. This in itself is an achievement, worthy of praise; therefore, from a distant far-away land, the palm groves by the Indian sea sing praises of his name.

True, by Rabindranath’s time, Shakespeare had become an inseparable part of the Indian subcontinent. Hence, it was natural for one master-artist to realise the efficacy of another.

Years after his death, in 1964, during Shakespare’s quatercentenary birth anniversary celebrations, the Calcutta Art Society presented an ivory tablet of the poem. This tablet became a part of the collection of translations of Shakespeare’s works in the Indian languages, preserved in the Shakespeare Centre Library.

Thirty years later, the then-Indian high commissioner to London, L.M. Singhvi, saw the tablet when he visited the Shakespeare Centre Library. As one who had been acquainted with Shakespeare’s work since his Allahabad days, Singhvi conceived of the idea of a permanent monument of Tagore at Stratford-upon-Avon. As the director and trustees of Shakespeare’s Birthplace agreed to his thought, he approached the then-chief minister of West Bengal, Jyoti Basu. Basu gave the task of sculpting a bronze bust of Rabindranath to the Kolkata-based sculptor Debabrata Chakraborty.

Finally on July 5, 1995, the bust was presented to Shakespeare's Birthplace Trust, to the chairman of the trustees, Stanley Wells and to the director, Roger Pringle.

The plinth is engraved with the poem of Tagore both in Bengali and in English. Rabindranath's lines are now on permanent display in the Bard's garden. The website of Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust further informs us:

“A plinth was designed by architect William Hawkes and made of York stone by The Linford Group of Lichfield. The French sculptress, Catherine Retailleau, engraved the plinth with Tagore’s poem to Shakespeare, following the Bengali script, and also Tagore’s own English translation. On the occasion, on September 20, 1996, of the dedication of the statue on its permanent site in the garden, flowers were laid by Mr Jyoti Basu and Mr Buddhadeb Bhattacharya, information and cultural affairs Minister of West Bengal, by Dr L.M. Singhvi and by professor Stanley Wells. The event was marked by songs in Bengali and in Hindi based on translations of the Tagore poem.”

The presence of Rabindranath at Shakespeare's garden made me wonder about the similarity between the reception of the two poets, playwrights, teachers and thinkers! Our Rabindranath is also a poet of the world, a bishwa kabi. Like Shakespeare, Tagore’s works have a broad, timeless appeal that we continue to celebrate.

Interestingly enough, as we celebrate Shakespeare Day here, Rabindra Jayanti is also celebrated in Stratford-Upon-Avon. This year, two organisations from the South Asian community were invited by Shakespeare's Birthplace Trust to mark Tagore’s birthday on May 4. To highlight the continued importance of his work and the interconnected relationship with Shakespeare, Rowshanara Moni, the famous singer and actress, will present musical pieces inspired by Tagore’s work. Senjuti Das, an Odissi dancer, will perform and engage in an interactive dance workshop.

This celebration of Tagore’s birthday has now become an annual event at Stratford, which speaks volumes about the overlapping territories of acclamation and celebration. Thus, in the third set of my life-tennis, I find myself as a ping-pong ball, looking at Shakespeare and Rabindranath, travelling to both the courts, one after the other, with elan. I will have to wait for the corn to ripe, to decide who won or whether anyone won at all!

Antara Mukherjee is assistant professor of English at the Durgapur Government College in West Bengal.

This article went live on May fourth, two thousand twenty five, at thirteen minutes past seven in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.