Anand Patwardhan on How to Watch One’s Country Die

“You’re going out, just put on [the sweater] and don’t use your brain,” says a slightly miffed Nirmala to her husband, Balu. “Okay, I’ll use a better brain. I’ll use yours,” Balu replies, laughing at her chiding. These are the two protagonists of Anand Patwardhan’s latest film The World is Family (Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam). They are his aging parents.

A sardonic mother, determined to finish her cigarette in peace and refusing to ‘behave’ for the camera, and a goofball father who responds to his wife’s harmless rebukes with nothing but giggles and smiles, make up the better part of the film’s 96-minute run-time.

On Tuesday (November 26), a packed hall at New Delhi’s Jawahar Bhawan got to see Nirmala and Balu on screen as part of a film screening organised by Nehru Dialogues.

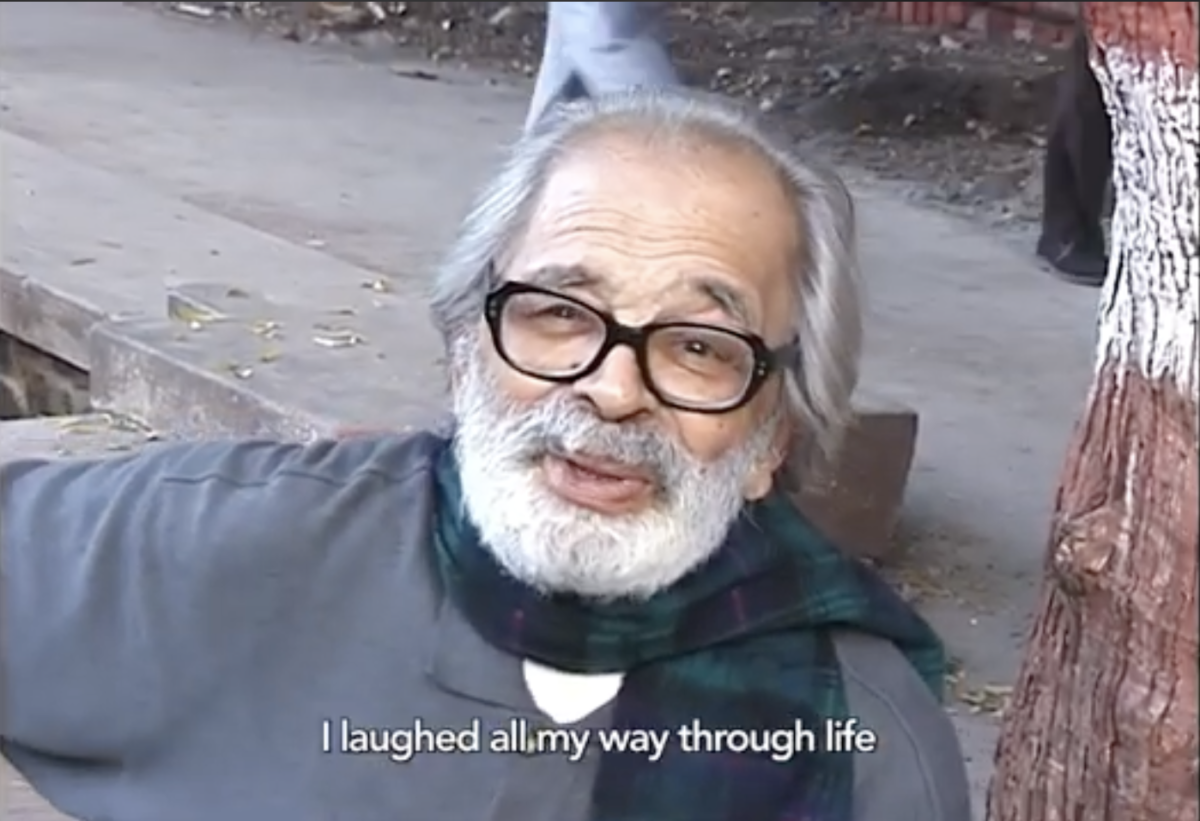

Anand Patwardhan at New Delhi's Jawahar Bhawan. Photo: Elisha Vermani/The Wire.

Patwardhan, despite his extensive and acclaimed oeuvre, approached the audience with the humility of an amateur filmmaker, feeling the need to caution them about the film. “I want to lower your expectations a bit. This film was not made with a lot of thought, it actually began as a home-movie,” he said. He was only partly telling the truth. The film did begin as a home-movie, but lack of thought is not a description that fits it.

“My parents were aging in front of my eyes. I wanted to keep their memory alive for myself so that’s why I began filming them. Nearly a decade later, I looked at the footage during the pandemic and realised that this had to be more than a home-movie. It became an oral history of the freedom struggle,” the 74-year-old filmmaker said.

Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam is a film as much about Patwardhan’s family, some of whom played a significant role in the freedom movement we come to learn, as it is about the ethos that India’s freedom fighters wanted the fledgling nation to imbibe. A nation that no longer exists, says Patwardhan.

Nirmala and Balu are no longer alive, in fact they die right in front of us on the screen. But the stories they have left in their wake are the ones we need the most today.

Anand’s mother, Nirmala Patwardhan, grew up in Hyderabad, Sindh (now Pakistan). She studied at the renowned Shantiniketan, where she developed an interest in pottery and met fellow artist Ira Chaudhari. Nirmala studied the artform around the world and went on to become a pioneering ceramicist and celebrated potter. But the only thing more impressive than her career as an artist is her wry humour.

A still from 'The World is Family'.

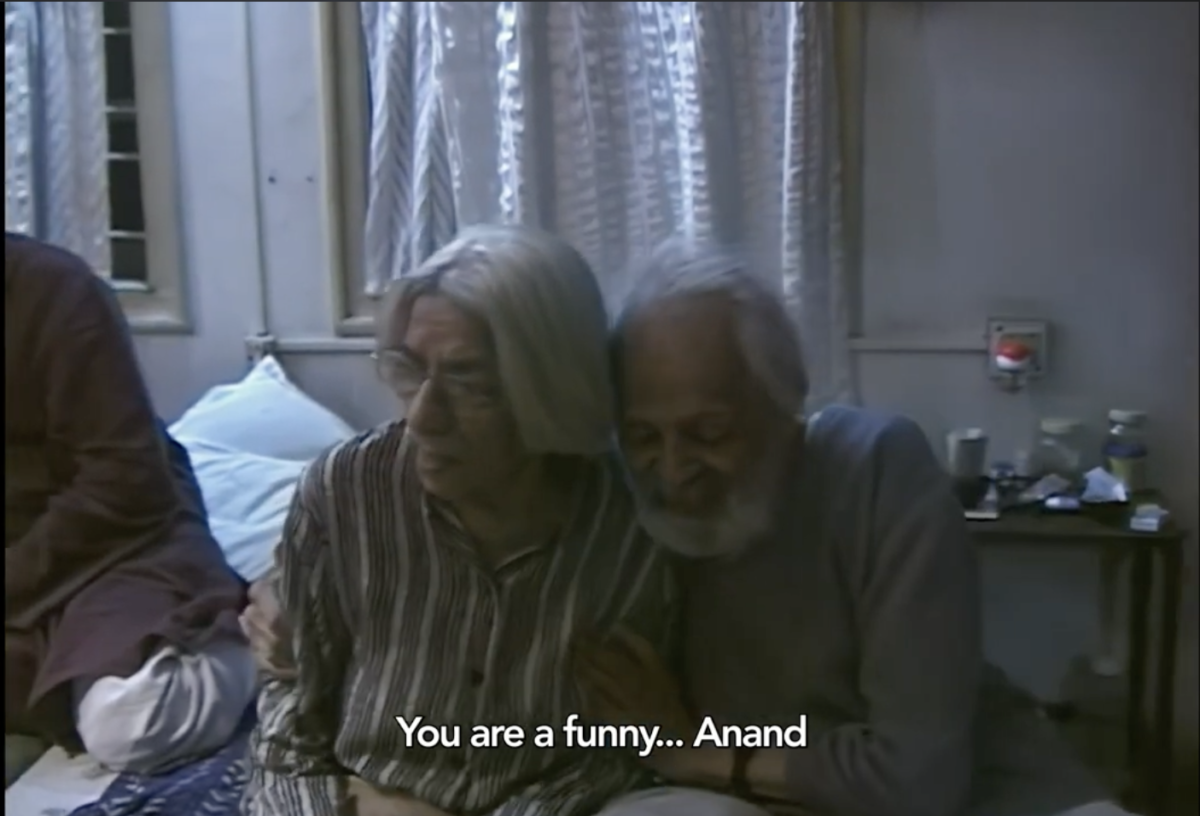

The conversation between Patwardhan’s parents is marked by a steady exchange of witty remarks and laughter, sometimes with and sometimes at each other.

One of the more heartwarming moments in the film revolves around Nirmala’s childhood home. Having been converted into a hospital after Partition, the staff and doctors at the facility welcome Patwardhan, who was on an informal peace visit to the country as part of Pakistan India Peoples Forum for Peace and Democracy.

They apologise for not being able to preserve the structure’s original character before showing Patwardhan around the house, doggedly explaining the parts that have been changed. “Please come and see the house, I invite you to Pakistan,” one of the senior doctors, beaming at the opportunity to speak to Nirmala on the phone, says with the warmth of a long-lost close relative.

On the other side of the family, Achyut and Puroshottam [Rau] Patwardhan, Patwardhan’s paternal uncles, assume the role of revolutionaries during the freedom struggle. Friends and family recount their stories, often forgetting that they’re on camera, which only speaks to Patwardhan’s craft.

A still from 'The World is Family'.

Through interviews with freedom fighters and relatives who remember Achyut and Rau sahab, Patwardhan stitches together a markedly different version of history than the one being popularised today. “I made the film because many, especially the younger generation today, do not know what really happened at the time. It’s important for them to see it,” Patwardhan says.

In one of the scenes, Patwardhan speaks to a young child, asking if the recent riots in his area were started by Hindus or Muslims. The young boy is steadfast in blaming the Muslims. “Hindus can’t do anything like this, it was them,” he says. Patwardhan asks if he would say the same thing if he were a Muslim. In response, the boy just looks at his feet – a quiet introspection brought on by Patwardhan’s gentle questioning. Later, he admits that it was the Hindus who started the violence.

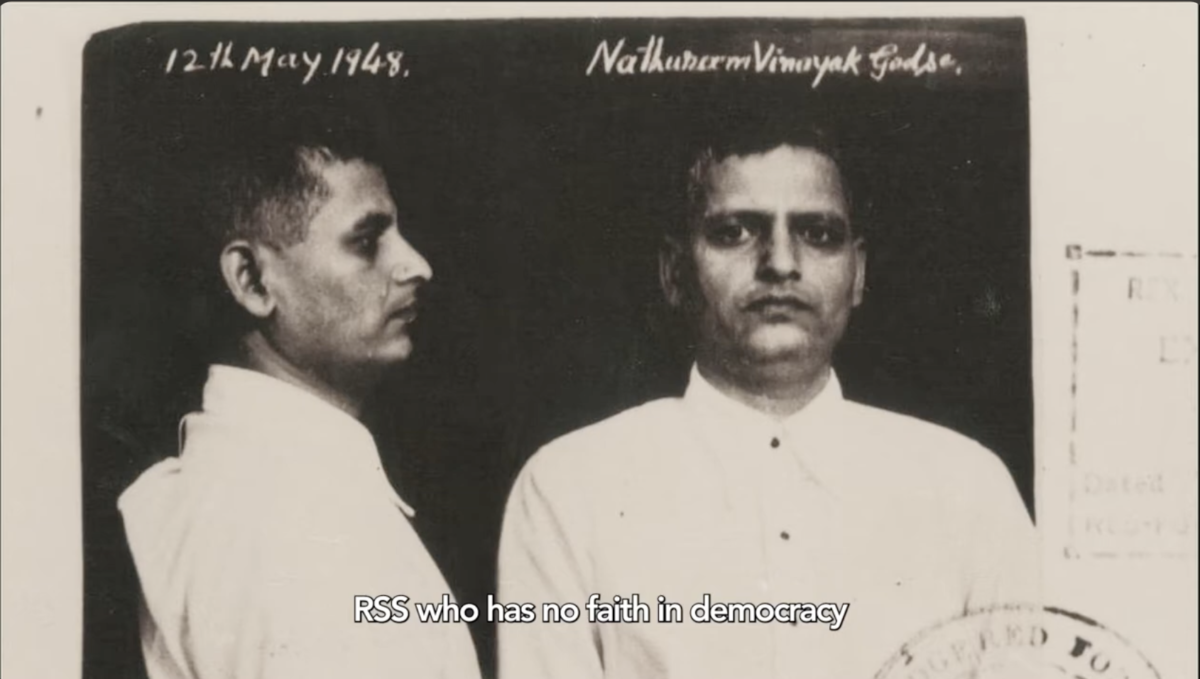

The film is unforgiving in its characterisation of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, holding “its product”, Nathuram Godse, responsible for Gandhi’s assassination without a hint of doubt. “The RSS has no faith in democracy, it has faith in violence,” one of his elderly relatives says.

A still from 'The World is Family'.

As the film weaves in and out of the freedom struggles’ trajectory, we watch Patwardhan’s parents grow older; learn how they met; of Gandhi’s opposition to their marriage; his handkerchief that was Nirmala’s prized possession, lost in the chaos of Partition and other chilling incidents that took place at the time.

“Someone went and told Gandhiji that my father was getting his under-age girl married to Achyut Patwardhan’s brother,” Nirmala recalls. “We were planning to tell Gandhiji that we married because we loved each other, but then he was shot the very same month,” she said.

In one of the last scenes where we see Nirmala and Balu together, they are celebrating their wedding anniversary. Balu, with his trademark goofy smile, walks slowly to sit by Nirmala’s side and hugs her. “Mummy had made papa promise not to die before her,” Patwardhan’s voiceover had told us in the beginning of the film. In the end, we learn that he keeps it.

This article went live on December first, two thousand twenty four, at fifty-eight minutes past two in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.