Marginalisation and neglect of certain social groups in democratic processes is injustice. Indian cinema for a long time has been dominated by the cultural and political interests of the social elites, disallowing any significant space to the voices and concerns of the socially marginalised communities, especially the Dalits. Though in the sphere of parliamentary democracy and in the arena of urban middle class establishments, the Dalit community has showcased their growing presence, the cultural industry has rarely reflected sensitively on their life experiences, social past and literary history.

Such functionality of the film industry is undemocratic as it lacks social diversity and participation of vulnerable social groups as partners in creating cinematic art. Ironically, even in the alternative mode of ‘progressive, critical or Left-oriented’ cinema, questions of caste emerged only as a peripheral topic. The scant Dalit representation within parallel cinema was stereotypical, mostly portraying the community as powerless victims of Brahmanical exploitation (remember Satyajit Ray’s Sadgati 1981).

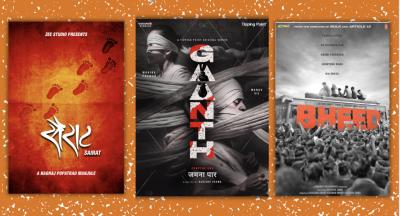

It is in the last 15 years that we have witnessed a sudden arrival of films that have introduced Dalit characters as dignified protagonists. These include a handful of films, particularly in Hindi (such as Masaan [2015], Bheed [2022], Shamshera [2022]), Marathi (Sairat [2016], Jayanti [2021]), and Tamil (Asuran [2021], Kala [2021], Kabali [2016]), some of which are directed by Dalit filmmakers like Nagaraj Manjule, Neeraj Ghaywan, and Pa Ranjith.

Such representation breaks away from the stereotypical portrayal of the community as victims and powerless figured, as shown in the parallel cinema of 1970s, and elevates them to someone bestowed with powerful heroic abilities, like in Majhi, the Mountain Man (2015), and Sarpatta Parambarai (2021). These films have initiated a more nuanced Dalit representation on screen. By introducing a new narrative style, realistic characters and authentic social background, these films disturb the conventional practices of cinema. Like the alternative modes of film narratives, Dalit cinema too offers an ideological battle against the populist-masala cladded entertainment flicks and raises challenges against the powerful ideological values of the indomitable cultural industry.

In this context, the latest web series on Jio Cinema, Gaanth Chapter 1: Jamnaa Paar (2024), can be seen as another important addition that supplements the growing appeals to have more representation of Dalit characters on screen. The series offers a robust Dalit character who is engulfed in everyday urban tragedies bestowed upon her due to poverty, sexual and caste harassment and institutional negligence. Her track in the series adds to the other powerful stories available on various OTT platforms that have previously provided significant space to Dalit characters on screen as protagonists. This is a significant development in the history of Indian cinema as it has birthed a young Dalit genre that has the potential to democratise the film industry substantially. For the better future of this genre, a strong support base should be established by industry leaders, and the state should implement effective policy measures to ensure increased participation of Dalits in the film industry.

Also read: Debate | The Return of the Dalit in the New Cinema of South India

Further, the proliferation of web based streaming services like Netflix and Amazon Prime have radically transformed the entertainment business in India. It offers exciting international content, introduces films that are critically acclaimed and also shows ‘original content’ filled with subtle anti-establishment voices. Stories with social sensitivity and political controversies have also gained a respectable space here, including the visible placement of caste and Dalit issues in the narratives.

Distinct from the conventional portrayals, a new set of Dalit characters have arrived that showcases them as the part of greater middle-class culture (Serious Men on Netflix) or as urban aspirants who wish to live a normal, dignified life (Paatal Lok 2020 (Amazon Prime). Importantly, the Dalit women characters in series like Maharani 2021 (Sony Liv), Aashram 2020 (MX Player) and Gilli Puchchi, an episode in the web anthology Ajeeb Daastaans 2021 (Netflix) further offered powerful Dalit women characters.

OTT and the making of the Dalit female protagonist

The character of Sakshi Murmu (Monika Panwar) in Gaanth: Chapter 1 Jamnaa Paar substantiates the ongoing trend by offering significant screen presence to a Dalit female lead. Though the story revolves around the Burai mass suicide case, it reflects upon the dark underbelly of urban development, showcasing how the inhabitants are yet to be distanced from religious orthodoxy, conventional caste customs and illogical rituals. Modern institutions like hospitals and police departments are portrayed as corrupt, insensitive places that are distanced from the ideas of justice and fairness. In such a depressing portrayal of the city life, we see the struggle of a young medical apprentice, Murmu, who accidentally gets involved in a criminal case. She eventually showcases her hidden talent to solve the mystery and emerges as a parallel protagonist in the narrative.

We decode that Murmu is a medical student from the reserved category who faces incessant caste-based harassment and discrimination. However, the series also portrays her as a gifted, analytical mind, curious to unearth the facts related to a tragic incident of homicide murders. She often ignores the everyday bouts of caste harassment but on occasions also demonstrates heroic impulses to register her protest against the perpetrators. Such nuanced portrayal suggests that though the caste system has not loosened its discriminatory grip over the Dalit community, they have this innate individual ability to escape the caste prison and perform as conscious and moral beings. Murmu’s honest determination to resolve the mystery successively overcomes the social and institutional barriers.

In earlier narratives (such as Gilli Puchchi), Dalit characters are depicted as being affected and burdened by Brahmanical patriarchy. However, they also exhibit the capacity and courage to emerge as heroic figures. This represents a substantive shift from the portrayal in parallel cinema, where Dalit women were often depicted as impoverished and perpetually exploited, as seen in Gautam Ghosh’s Paar (1984), or violated and raped by dominant caste elites with near impunity in Nishant (1975) and Damul (1985), and lacking the agency to challenge such atrocities. The current scenario suggests that social control and prejudices against Dalit bodies are subtly receding, allowing Dalit characters, including women, to be presented as liberated individuals.

In another example, we see Pallavi Manke (Radhika Apte), in the web-series Made in Heaven, a proud Dalit professor, working at an Ivy League university, and has no hesitation to flag her ‘ex-Untouchable’ identity. Though she is marrying a sensitive and progressive Indian-American lawyer, she faces social burdens and anxieties when she offers to add a Buddhist ritual to her marriage ceremony. The story is beautifully woven, representing the social principles that Ambedkar wanted to establish in India’s social life. Like these stories, Murmu is also showcased as a protagonist with abilities that can challenge the conventional patriarchs and emerge as an inspirational character in the narratives.

Also read: The Dalit Person in Mainstream Indian Cinema

Such characters have certainly sown the seeds for the emergence of a Dalit genre in Indian cinema, though it is still in its nascent stage. There is a growing possibility that this young yet impressive presence of Dalit characters could soon develop into an influential genre. Like other significant genres – parallel cinema, Muslim social, or the recent Hindutva-based films – Dalit cinema has yet to make its mark on the film industry. For Dalit characters to become significant in mainstream movies and on OTT platforms, a radical shift in the social psyche of filmmakers is required.

Future of the Dalit cinematic genre

Dalit cinema has surely initiated a reform as more creative artists from marginalised social groups join the film industry to showcase their stories. These narratives offer organic cinematic content without diluting the entertainment quotient. Though many of the films have impressive box-office success – like Sairat, which is the biggest blockbuster in Marathi cinema till date – this genre is yet to build a substantive mass following and has little power to radicalise the popular and conventional patterns of film making. It has initiated a steady, if slow, movement for a much-needed democratisation of the film industry. However, without the support of the conventional leaders of the industry, it will remain a marginalised genre.

Dalit cinema is inspired by the fascinating success of Black American film fraternity and other minority groups that argue for diversity and social harmony in the cultural industry. It is equally important that the Indian cinema industry learn from Hollywood’s fascinating social experiences and cultural innovations that has made Blacks, Asians, Jews and other minorities not only a significant part of cinema narratives, but also as influential artists, creators and producers. Given India’s own diversity in terms of culture and caste, it is essential for industry leaders to explore how cultural institutions can become more democratic and representative of these social nuances. Representing the people that have historically remained outside the purview of mainstream cultural practices will showcase that the Indian film industry cherishes liberal-democratic credentials and it is not an exclusive domain of few rich classes and social elites.

It is an appropriate time for the film fraternity to recognise and collaborate with the outstanding cinematic works of artists and producers belonging to the socially marginalised communities, elevating them as an inspiration for the new generation. New cultural festivals, public institutions and policy frameworks by the state are required to promote the culture and talent of diverse social groups that are often marginalised in mainstream discourse on cinema and art. It is essential to create new platforms and for existing popular culture establishments to adapt in order to connect producers, artists, and technicians from Dalit backgrounds for future collaborations.

Furthermore, it is crucial for Dalits to also enter the film industry as producers, technicians, and directors to showcase their stories and talents more prominently. However, both of these possibilities face numerous obstacles. It is high time that the emerging Dalit genre be recognised as part of the reformist cinema movement, driven by a vision that cinema has a critical role in demonstrating social diversity and promoting the values of social justice. Such cinema would create an independent platform for artists, creators, and film enthusiasts to build and celebrate an alternative cultural space, highlighting the dignity and diversity of historically marginalised social groups and integrating them into the cultural industry.

Harish S. Wankhede is Assistant Professor, Center for Political Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.