NHRC to Visit Nashik Prison Five Years After The Wire's Report on Custodial Death

Mumbai: Five years after a life convict wrapped a suicide note in a polythene bag and swallowed it before hanging himself from a ceiling fan inside Nashik Central Prison, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) has formed a committee to conduct a “spot investigation” into the matter. Thirty-one-year-old Asghar Ali Mansoori had named five prison officials in his letter.

Mansoori died by suicide on October 7, 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the police, Mansoori had strung together the elastic straps of masks used during the pandemic and hanged himself from a ceiling fan. Mansoori’s father Mumtaz Ali has questioned this claim. “How can a full grown man, weighing over 75 kilos, hang himself with the flimsy elastic straps of surgical masks?” he had asked.

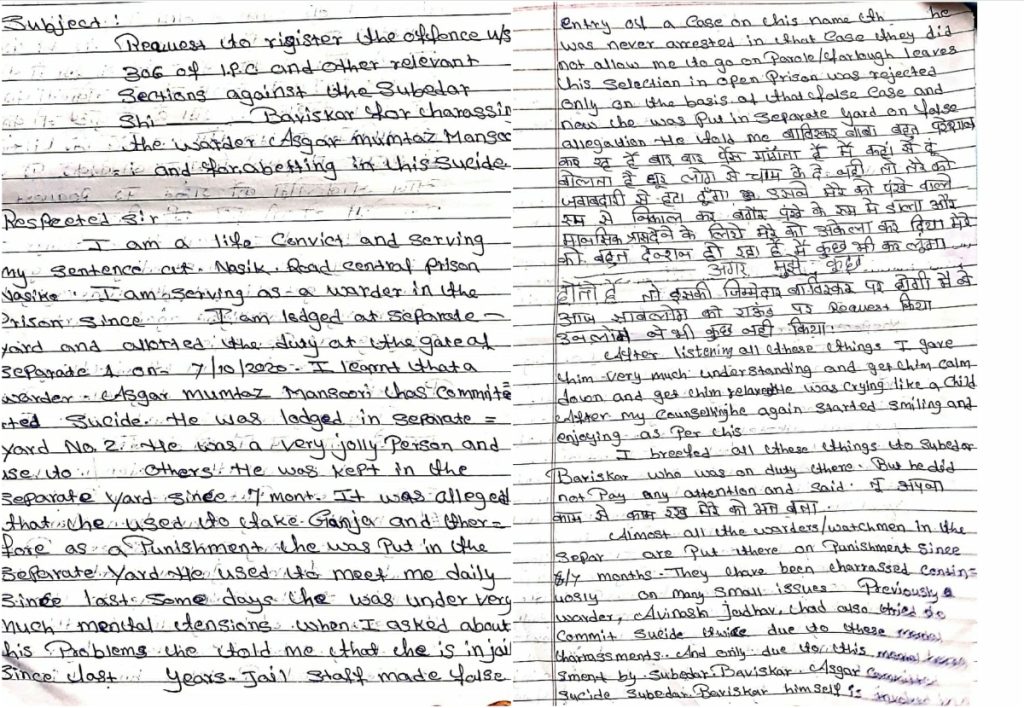

Afraid that the suicide note – the only evidence of the torture he was allegedly subjected to – would be destroyed by jail officials, Mansoori had swallowed the note. The suicide note was found in his abdomen at the time of the post-mortem. The note, which should have been considered a “dying declaration” in this case, was ignored, and the Maharashtra police refused to investigate the matter. Some of the accused prison officials have been transferred to other jails; a few have retired.

Five years after the incident, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) has decided to make a “spot visit” to the prison. The incident was first reported in The Wire, and the commission is making this visit following two complaints made on the basis of The Wire’s reporting.

A screengrab taken during a video call between Asghar Ali Mansoori and his family members. Mansoori would speak to his family at least once a week on a video call. Photo: By arrangement/The Wire.

Mansoori had been in prison for a little over 14 years in connection with a murder case. As a long-serving prisoner, Mansoori was working as a jail warder. At this job, Mansoori wrote in his note, he was harassed and punished by prison officials. Mansoori was kept in solitary confinement as part of his “punishment” for close to a year. He was depressed there and made several requests to the prison officials to move him back to a general ward along with other incarcerated persons.

During the pandemic, as incarcerated persons were cut off from the outside world, Mansoori could only contact his father over video calls. During those weekly calls, Mansoori had allegedly mentioned to his father the harassment he was facing, his father, Mumtaz Ali, told The Wire.

Mansoori’s suicide note has harrowing details of the roles played by the five prison officials in harassing and torturing him. The note mentions only their last names – Baviskar, Chavan, Sarpade, Gite, and Karkar.

A letter and a report

Following Mansoori’s death, six of his co-prisoners, all convicts, had written letters to the Chief Justice of the Bombay high court narrating the living condition in Nashik prisons and the ill-treatment meted out to prisoners in the hands of the prison officials. No action was initiated on these letters.

After The Wire reported the incident on October 14, 2020, author and researcher Sanjoy Hazarika and human rights activist Dhana Kumar registered two separate complaints with the NHRC. Kumar works with the National Campaign Against Torture, an organisation that looks into cases of torture across India.

The commission had conducted the first hearing on October 29 of the same year. The commission has since demanded an investigation report from the Nashik prison authorities, the district collector’s office, and the police commissioner of Nashik. Notices were issued time and again, but no response was received.

In October 2022, the NHRC issued a strict warning to the state authorities, asking for a detailed report and stating that if they failed, action would be initiated as per the Protection of Human Rights Act against them, the commission wrote in its order. In response, a few incomplete documents were provided.

Dushyant Singh, the Deputy Superintendent of Police who is deputed at the NHRC at present and who will be visiting Nashik Prison today (October 6), told The Wire that the delay in the investigation happened primarily due to “non-cooperation” from the state authorities. “Even after five years, we have not received the magisterial inquiry report in the case,” Singh told The Wire.

In the high court

Mansoori, on his death, had ensured he left vital evidence against the jail officials. In the suicide note he had narrated the circumstances under which he was pushed to end his life and also identified those responsible for his death. The police, however, did not pursue the case.

Wahid Shaikh, a prisoners' rights activist, had helped Mansoori's father Mumtaz Ali move the Bombay high court seeking an investigation and compensation for his son’s death. The case came up for hearing a few times, and since 2023, there has not been any significant development in the matter, Mumtaz Ali’s lawyer, Vijay Hiremath, told The Wire.

During the last hearing, the high court had directed the state to submit a copy of the judicial magistrate’s report to the court. In the case of death or rape in custody, the state is legally bound to carry out a judicial magistrate inquiry under Section 176(1A) of the Code of Criminal Procedure (Section 196 under the new Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita).

Hiremath confirmed that the judicial magistrate’s inquiry report was not provided to Mansoori’s family, and Singh confirmed that it was not submitted to the NHRC either. Shaikh pointed to the delay by both the court and the NHRC in handling the case. “Custodial torture and deaths are difficult to prove. But here, the victim had left a suicide note with clear roles attributed to the accused persons. Yet no action was ever initiated,” Shaikh said.

After Mansoori’s death, several incarcerated persons lodged with Mansoori in Nashik Prison came forward to complain about the ill-treatment meted out to Mansoori and the ongoing torture they were subjected to for speaking up. One of them, a convicted prisoner, wrote a detailed letter giving details of the ill-treatment and had the letter sent to The Wire through a lawyer. In the letter, he claimed that some prison officials – also named in Mansoori’s suicide note – were allegedly involved in smuggling ganja inside the prison premises and had suspected that Mansoori was revealing their involvement to higher prison officials.

A letter written by a prisoner of the Nashik jail, accusing staff of harassment and corroborating Mansoori’s claims. Photo: By arrangement/The Wire.

This prisoner, who wrote the letter, was later brutalised and moved to Nagpur Prison, just to prevent him from deposing before a judicial magistrate. He moved the Bombay high court. “The court had directed me to go visit him at Nagpur Prison. Since his living conditions had slightly improved there and he was no longer facing harassment, he continued to be lodged at Nagpur, and the petition was disposed of,” his lawyer, Mohammad Abidi, told The Wire.

Like this person, there were several others who had come forward to testify before the judicial magistrate. One of them, V. Patil, now a practicing lawyer at the Bombay high court, told The Wire that the prison officials left Mansoori with “no other choice but to kill himself”. “We had witnessed his daily harassment. On one occasion, a prison official had publicly thrashed and insulted him for trying to raise a complaint with the prison superintendent,” Patil alleged. Mansoori’s suicide letter has a mention of these ill-treatments.

The NHRC’s spot investigation, however, is coming up after five years.

Mumtaz Ali, who moved the court demanding an investigation and also followed up with the Nashik police station to investigate his son’s death, told The Wire that he was simply asked to be present before the NHRC. “I am an old man and can barely make ends meet. For the past five years, I have spent all my energy and resources getting the state to find out who pushed my son to death. I just hope the NHRC does justice.”

This article went live on October sixth, two thousand twenty five, at seven minutes past nine in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.