Sonbhadra’s Malaria Crisis: How Collaboration, Rigorous Surveillance Can Help

Sonbhadra, Uttar Pradesh: Savita Devi associates rain with death.

Last September, within a span of 10 days, the 30-year-old farmer and her husband Raju (he uses one name) belonging to the Baiga community, a scheduled tribe, lost five of their seven children to malaria as the southwest monsoons pounded their village, Pausila.

With neither mobile phone nor road connectivity, Pausila – in the hills of Sonbhadra district in Uttar Pradesh – is a scatter of mud-walled huts dotting the hillsides. Farmers like Raju and Savita Devi eke out a living from the few acres of land they call home.

Opening a tin trunk in a corner of her hut, Savita Devi pushes aside sundry items to come up with photos of two of the dead children – her sons Chandan aged 8 years and Sooraj, even younger.

“I have just these two photos left, Raju burnt the others. He wants me to get over the loss of our children, but look at them…what round faces and big eyes! I always wanted to remember how they looked as children after they grew up, and now this is all I am left with,” she says.

During the malaria outbreak, “Bahut ladka mare rahe paar saal. Kareeb 50-60 [Many children had died last year. Almost 50-60],” she adds.

Nirmala Devi, the accredited social health activist (ASHA) for Pausila, puts the figure at 22; and the National Centre for Vector Borne Disease Control (NCVBDC) at zero. IndiaSpend has reached out to the NCVBDC for comment. We will update this story when we receive a response.

Sonbhadra has several factors that make it susceptible to malaria: It has a high forest cover, with tribal populations in hard-to-reach habitations, and the district borders four states, attracting migrant workers searching for work in the power plants and allied units. Therefore, increased surveillance to detect outbreaks and multi-sector collaborations including inter-state collaborations are critical, as we explain below.

A potentially life-threatening disease, malaria is caused by microscopic parasites grouped under the Plasmodium genus. According to the NCVBDC, most cases of malaria in India are caused by Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum. Anopheles mosquitoes breed in stagnant water such as in the pools and puddles that form during the monsoons.

Sonbadhra is full of them, as IndiaSpend reported in the first part of this series. The terrain is pockmarked by pits filled with rainwater that stagnate for months, providing rich breeding sites for Anopheles.

This reporter filed a right-to-information (RTI) request with the National Vector-Borne Diseases Control Programme, under the NCVBDC for data on district-wise malaria testing, caseloads and fatalities on April 24, 2024. The RTI response dated May 17 revealed that Sonbhadra recorded 300 malaria cases in 2023, the seventh-highest in the state but had the highest (65%) P. falciparum burden, the kind which is more serious and likely to kill. The District Malaria Unit has placed 196 villages out of 1,440 in Sonbhadra on red alert for malaria. Pausila is one of the hotspots.

The tyranny of distance

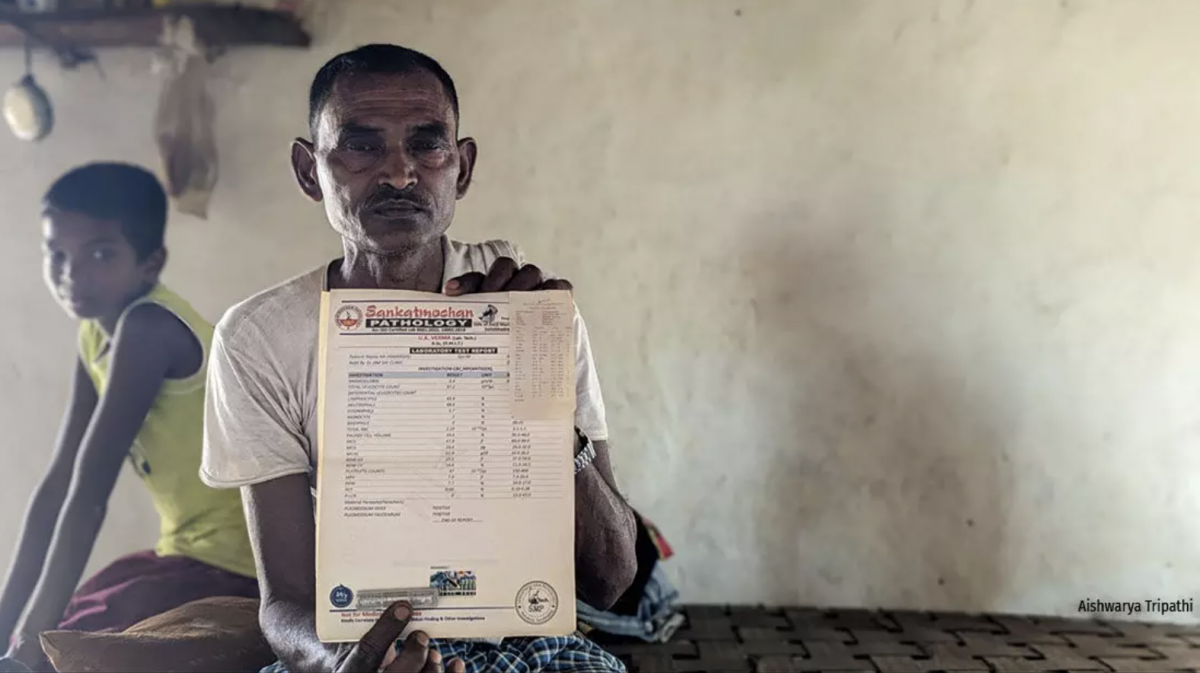

In a cluttered mud hut, lit by a single tiny window, 58-year-old Janakdhari (he uses one name) searched through a white cloth bag for the lab reports and death certificate of his three grandchildren – Ankush, Himanshu and Divyanshu – and daughter-in-law Sushila (30) who died of malaria in November 2021.

“Poora ghar bigad gaya hamara [My entire family got broken],” he rued.

The four had been rushed to a private hospital 32 km away where they tested positive for malaria. Himanshu and Divyanshu tested positive for both P. falciparum and P. vivax. The death certificate issued by the District Combined Hospital in Sonbhadra states that Ankush had tested positive for P. falciparum. The NCVBDC recorded zero deaths in Uttar Pradesh in 2021.

Shock and fear had swept up the villagers on witnessing the deaths in Janakdhari’s house. “So many people died that year. Then sahabs came to test everyone,” recalled 52-year-old Kamalbhan, Janakdhari’s neighbour.

Fifty-eight-year-old Janakdhari holds up the positive malaria test report of his grandson Himanshu. Three of his grandchildren – Ankush, Himanshu and Divyanshu – and daughter-in-law Sushila had died of malaria in November 2021. Photo: Aishwarya Tripathi.

Surveillance is stated as a core strategy of the National Strategic Plan for Malaria of 2023-2027, with forests, tribal and border areas and migrant populations as targets of special attention. Sonbhadra checks all the criteria, with about 37% forest cover, 21% tribal population, borders with four states, a substantial number of migrants, and scattered, hard-to-reach habitations. Yet, surveillance is lagging.

“There are many villages here in Sonbhadra with no proper roads and even if there is a road, the houses are scattered around in the hills. An ASHA has to walk at least 2 km to get from one house to another – that’s the biggest surveillance-related challenge,” said Dharmendra Srivastava, Sonabhadra’s district malaria officer. Sonbhadra has a population density of 270 per sq km of hilly terrain, a third of the state average of 829.

The NCVBDC tracks malaria by examining blood smears collected from the population. An Annual Blood Examination Rate (ABER), which is the percentage of the population tested for malaria, should be at least 7% in areas that have malaria year-round, and 5% in areas of seasonal transmission.

In Uttar Pradesh, which is categorised as a “low-transmission state” overall, the average ABERs rose from 1.19% in 2020 to 4.5% in 2023. Further, only 25 of the state’s 75 districts had an ABER more than the required 5% last year. Surveillance in some districts, such as Budaun (10%), Amethi (9.3%) and Ghaziabad (9%), has fared better. In Sonbhadra, the ABER rose from 3.31% in 2020 to 8.17% last year.

“We need a constant presence of health workers who go to the field every fortnight for collection of blood slides or by using Rapid Diagnostic Test kits. When surveillance is poor, transmission goes undetected,” said Ramesh Dhiman, former scientist-G, Indian Council of Medical Research-National Institute of Malaria Research, who is currently the national coordinator for the Global Fund for Malaria, an international financing and partnership organisation to end the epidemics of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria.

“Cases can increase all of a sudden and only when people start dying does the healthcare department come to know that there is an outbreak,” he added. Dhiman’s observation rings true in the case of both Janakdhari and Savita Devi’s families, where the health department’s response came too late.

“After so many children died, that’s when the gaadis [government vehicles] showed up and started testing everyone,” lamented Savita Devi. Her daughter Suman, who was also sick with malaria, was saved after the officials arrived and began treatment.

In Makri Bari village, 40 km from Pausila, it was the death of 75-year-old Parvati Devi on July 27, 2023 which rushed the district-level officials to the village.

“I remember after the budhiya’s [old lady’s] death, we conducted testing using rapid test kits for four days continuously in the village school from morning till evening,” said Rajeshwari Devi, an ASHA serving Makri Bari since 2006. “Afsars [officials] had come here all the way from Lucknow to check if there is any stagnant water around Parvati Devi’s house.” (State capital Lucknow is 400 km away.) Parvati Devi’s son Ramesh Pal nods in sober acquiescence. However, her death is registered as a case of diarrhoea in the official records.

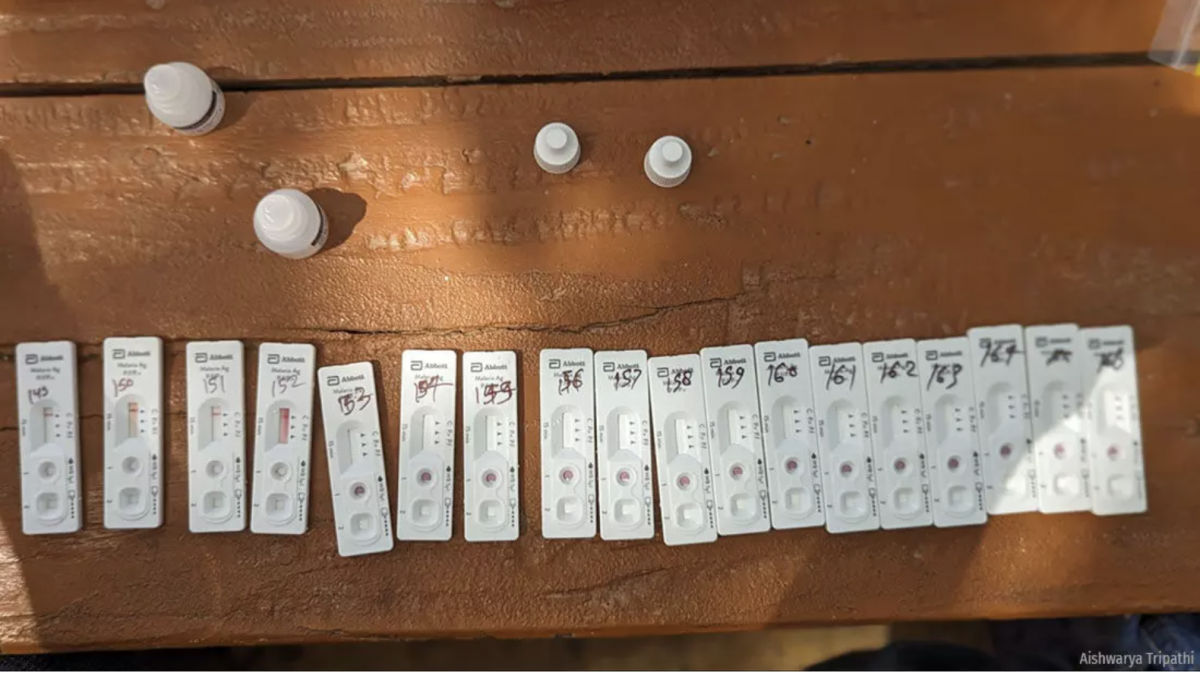

Rapid Diagnostic Kits for malaria. When Savita Devi’s son Chandan fell sick, ASHA Nirmala Devi did not have the Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) kits on hand, but she alerted her health sub-centre about the outbreak. Photo: Aishwarya Tripathi

The problem with official registration of deaths in India is not new, and came into sharp focus during the Covid-19 pandemic, as IndiaSpend reported in May 2022. Even earlier, nine out of 10 deaths in India were registered in 2019, but rural areas and less developed states reported lower levels of registration. Only a fifth of deaths that year were medically certified, and more often than not with the underlying cause of death recorded incorrectly, as IndiaSpend reported in June 2020.

ASHAs, the superheroes

Sonbhadra’s District Malaria Unit comprises a District Malaria Officer, an assistant malaria officer, a vector-borne disease consultant, four inspectors and one senior field worker. ASHA workers are the only surveillance support.

Some 1,527 ASHAs cater to the district’s population of 1.86 million and malaria is only one of the many conditions they track – apart from diarrhoea, tuberculosis and malnutrition. An ASHA worker gets Rs 15 for each malaria test they conduct and Rs 75 for every positive case they record in the malaria register. An additional Rs 200 is given for following up on a registered case. ASHAs are the primary source of information on which the district health department acts to set up malaria camps in the villages.

When Savita Devi’s son Chandan fell sick, ASHA Nirmala Devi did not have the Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) kits on hand, but she alerted her health sub-centre about the outbreak. In January this year, Nirmala Devi was given 20 malaria RDT kits. Five were left unused as of April 10, 2024, as Nirmala Devi cannot get to Pausila without transportation aid from her husband, who has been occupied with wheat harvesting.

Soaring temperatures and heat waves also impair the ASHAs’ efficiency. On May 6, as the temperature rose to 40oC, Pratima Devi who supervises the work of 18 ASHAs in Makra Gram Panchayat in Myorpur block complained of severe headache after the day’s surveillance work. “Every other day I get a call from some ASHA worker who has symptoms of heat-related diseases like diarrhoea, dehydration or headache. But it is important to visit the houses, we need to ensure that no malaria-related deaths happen in our region,” she said.

An ASHA worker displays the malaria register. Given the low population density in Sonbhadra’s villages, ASHA workers typically walk 2 km from one household to another. Photo: Aishwarya Tripathi

Surveillance is patchy also because homes away from the villages get missed. “We limit our identification of malaria hotspots at the village level, and not further afield, because we have just one senior field worker,” said Shubham Singh, vector-borne disease consultant, Sonbhadra.

Poor internet connectivity too impairs outbreak responses, said Ashok Kumar, pharmacist at the Pachpedia Primary Health Centre near Pausila. All malaria cases are supposed to be logged into the government's Unified Disease Surveillance Platform, but “it takes almost 15 minutes to upload information about one case because of poor internet access in the region. This becomes an additional burden if the patient flow is high,” he said.

In 2018 and 2019, Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, had a fifth of all malaria cases in the country, followed by Chhattisgarh (18.3%). Detection is patchy, however, as evidenced by the erratic case load each year: in 2020, the state reported 28,668 cases. The number fell to 10,792 in 2021 and to 7,039 in 2022. In 2023, the caseload spiked to 13,603 cases, an increase of 93.25% from the previous year. Testing rates fluctuated – from 2.01% in 2017 to 2.32% in 2018 to 1.8% in 2021, before recovering to 4.5% in 2023.

Besides the annual caseload, a key parameter on which the malaria control is judged is the Annual Parasite Incidence (API), which measures the number of cases per 1,000 population in a region. A region with API less than 1 is considered a low-transmission area. In 2015, Uttar Pradesh was tagged as a Category-2 State (with API< 1 and with some districts having API > 1). In 2022, it transitioned to Category 1 (states with API < 1 in all districts). This low API allows Uttar Pradesh to maintain its status of low endemicity.

However, a research paper published in PLOS Global Public Health points out that API can be relied upon only in high and moderate transmission risk areas where ABER and fever surveillance are robust. With the state testing less than an average of 5% people for malaria in 2023, and likely picking up just a fraction of the total, the corresponding API makes the risk of malaria appear much lower than it actually is.

A woman has her blood drawn for malaria testing at a camp set up in rural Sonbhadra.

Population-level statistics tend to miss hotspots of malaria, which need higher levels of testing. Photo: Aishwarya Tripathi

“In a densely populated state like Uttar Pradesh where malaria is often clustered to specific pockets, calculating malaria rates like API based on the entire population of a district or the entire state presents a misleadingly low magnitude of the problem and provides a blurry picture of the malaria situation in the state,” observed Atul Kumar, India Programme Head - Health at Prayatna, a non-government organisation focused on improving the quality of life of the most marginalised communities. “This prevents private corporations from investing in efforts to fight the disease through their social responsibility programmes.”

Another tool to predict malaria outbreaks is the Mosquito Density Index (MDI), calculated by dividing the number of mosquitoes or their eggs captured in a given area by the number of inspected traps. The number varies seasonally and gives an idea of mosquito numbers: the higher the MDI, the greater the risk of malaria.

“We need research to correlate the MDI with an outbreak. Our planning is based on just the occurrence of cases, with no prevention strategies based on the mosquito density in a specific area,” said Dhiman.

Vikasendu Agarwal, state surveillance officer, agrees. Seated at his table in a tiny cubicle inside the Department of Communicable Diseases in Swasthya Bhawan, Lucknow, the doctor simultaneously answers my questions on mosquito density, works feverishly on his laptop, and responds to a non-stop stream of requests from colleagues and visitors. Though tracking the MDI needs to be a year-round activity, said Agarwal, it is simply impossible when there are just a few entomologists available in the district.

“It is done more meticulously between April to October in high caseload districts like Bareily, Badaun and Pilibhit and not so regularly in districts like Sonbhadra who have brought down their malaria caseload over years,” he explained. Despite repeated attempts, no data could be obtained pertaining to the mosquito density index from the Integrated Disease Surveillance Unit, Uttar Pradesh.

Officials stepped up malaria surveillance in Sonbhadra after the killer outbreak last year. However, malaria control needs more than surveillance. An outbreak investigation in Bareilly district, for instance, revealed that apart from poor surveillance, a combination of excessive rainfall, lack of laboratory facilities and tardy responses all increased the risk of infection, illness and death.

One Health approaches essential to beat malaria

Besides the risk factors in Bareilly, Sonbhadra has distinct intersectional vulnerabilities to malaria that signal the need for a One Health response. The World Health Organization defines One Health as an approach to designing and implementing programmes, policies, legislation and research in which multiple sectors communicate and work together to achieve better public health outcomes.

The One Health approach is critical to addressing health threats like malaria that flare up in the animal-human-environment interface and Sonbhadra is a textbook example. It is the only district in India which borders four states: Bihar’s Kaimur and Rohtas districts to the northeast, Jharkand’s Garhwa district to the east, Koriya and Surguja districts of Chhattisgarh to the south, and Singrauli district of Madhya Pradesh to the west. All of these districts are endemic for malaria, Singh said, and have high rates of migration to Sonbhadra where the National Thermal Power Corporation offers a steady stream of jobs.

“We are dealing with a unique problem. Every day almost 12,000 people from the malaria-endemic bordering states enter Sonbhadra for work. It is difficult to keep track of this migration, which has the potential to aggravate malaria transmission in Sonbhadra,” explained Singh, the district vector-borne disease consultant.

Savita Devi’s village, for instance, is an 11-km walk from the border of Madhya Pradesh.

“Surveillance becomes challenging because of the mobility of migrants. If one day somebody has tested malaria positive and the next day they migrate to Chhattisgarh, our team might not be able to track the patient till they come back,” he added. The Malaria Elimination Programme Review India 2022 highlights migration from high to low transmission districts as a research priority. India’s malaria elimination strategy for 2023-2027 notes that elimination and attainment of malaria-free status will require cross-border collaboration at international, interstate and inter-district borders. In practice, this is proving difficult to do.

“Practically it’s not possible for the health department to keep track of the migrant population, considering we are already overburdened,” said Agarwal. Migrant affairs come under the labour department, which is missing from the list of 13 other departments that the state’s Department of Communicable Diseases collaborates with to tackle vector-borne diseases including malaria.

The 13 departments are: Department of Health and Family Welfare, Department of Women and Child Development, Rural Development Department , Department of Panchayati Raj, Urban Development Department, Directorate of Medical Education and Training, Department of Basic Education,Department of Secondary Education, Department of Agriculture, Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying, Empowerment of persons with Disability Department, Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Information Department.

Sonbhadra and its cross-border neighbours share a similar climate with matching rainfall and temperature trends.

The district’s forest cover of 36.79% is also much like that of Singrauli in Madhya Pradesh (38.42%), Kaimur in Bihar (41.12%), Garhwa in Jharkhand (34%), while it is lower than Koriya (62.03%) and Surguja (45.02%) in Chhattisgarh. The ecological similarity suggests that malaria transmission patterns may well be similar across borders, signalling an opportunity for better preparedness by exchanging epidemic intelligence.

With the climatic window for malaria transmission widening, as we reported in the first part of this series, cross-border initiatives are urgently needed. Basuhari village, on the banks of Son river in Nagwa block of Sonbhadra, is a place at high-risk for malaria, as categorised by the District Malaria Unit. Across the river lies another malaria-endemic village in Garhwa district of Jharkhand.

“Their challenges might be similar to ours. It will be interesting to know how they are controlling the malaria cases in their district. But at district-level we aren’t having any cross-border collaboration that I am aware of,” said Srivastava, district malaria officer of Sonbhadra. The RTI response from the NCVBDC showed that last year, Garhwa recorded 176 malaria cases, with an API of 0.1 as compared to Sonbhadra’s 300 cases and API of 0.14. However, it tested about 14 in 100 people (ABER 13.55%), whereas Sonbhadra’s testing stood at about 8 per 100 people (ABER 8.17%).

“There is no geographical boundary in malaria transmission, so collaboration of different sectors as well as states becomes important,” said Dhiman. “... multi-sectoral collaboration is happening, I would say. Things are in good shape in terms of policy and the guidelines of the national elimination programme, all we need to ensure is proper implementation,” he added.

Basaniya tola in Pati Gram Panchayat, Myorpur block on the banks of the Son river. Photo: Aishwarya Tripathi

The climate data metric

Climate change can push malaria transmission from endemic to non endemic areas, explains Rajib Chattopadhyay, Scientist at India Meteorological Department, Pune who also heads the Climate Application and User Interface team and studies the correlations between climate and health. Looking for patterns from climate data and malaria-related health data can be crucial in this regard. The Department of Meteorology could of course help, but it is not listed among the 13 governmental partners of the state's Department of Communicable Diseases. The department of Environment, Forest and Climate Change is also absent.

“Robust testing is critical during erratic heavy rainfall and warmer temperatures,” says Chattopadhyay. “We need more localised efforts to tackle diseases like malaria whose vector responds to local factors including climate variables. Low surveillance in these times of climate change can derail the national elimination goal of 2030,” he warned.

The IMD Pune puts out a Global Forecast System-based weekly bulletin on the evolution of the transmission window for malaria. “This can be helpful for better malaria surveillance and aid the states to plan beforehand and better,” said Chattopadhyay, who heads the project. However, what is missing are the health data necessary to build more intricate climate-health prediction models with better accuracy, he added.

How collaboration can help: A case study from Odisha

A team of researchers and public health professionals in Odisha headed by Kaushik Sarkar, Director, Institute for Health Modeling and Climate Solutions (IMACS), launched a multisectoral, multidisciplinary response to introduce a climate-smart health system for malaria. The project was funded by Reaching The Last Mile through the Forecasting Healthy Futures initiative.

Sarkar’s team operationalised Fever Treatment Depots in two of the most challenging hotbeds of malaria in southern Odisha – Koraput and Malkangiri – and leveraged artificial intelligence (AI) to improve decision-making and strengthen the delivery of services at the grassroots. His team used AI and Big Data Systems to collate almost 130 ecological factors including temperature, soil and vegetation indices, land use, type and number of extreme weather events, forest cover, humidity, and rainfall range, and studied how these factors influenced the occurrence of fever and malaria in those districts. The project was successful with the support of the Odisha government and the IMD as well as with scientific inputs from both Dhiman and Chattopadhyay who are part of IMACS’ global expert network.

While other early warning systems simply predicted whether or not an area was malaria-prone, Sarkar’s model forecasted the approximate number of cases in the area of interest.

“The idea was to anticipate the increase or decrease of malaria cases, identify outbreak-prone areas beforehand and not after the transmission has already begun. This was to facilitate a target-based approach of the health department for surveillance and the provision of healthcare services,” Sarkar said. This climate-based malaria prediction model had an accuracy of 94%, allowing an error margin of plus/minus 6%. That is, if the model predicted 100 cases for a specific sub-centre in a given time, the actual malaria cases in that sub-centre ranged between 94 and 106.

“The sub-centres where the model was implemented saw a relative decline of 70-80% in malaria cases because of this targeted approach,” Sarkar explained. “The same government routine interventions were getting delivered in these regions; the only difference was that they reached the spots where they were needed and meaningfully engaged communities. Imagine how efficient we can be and how many resources the government can save if we move to a targeted approach.” he explained.

Hitting the nail on its head

While Uttar Pradesh is yet to progress to a climate smart health system for malaria, Vikasendu Agarwal credits diligent surveillance, public awareness campaigns and case follow-up as strategies that historically helped reduce the caseload in the state.

Like six other malaria endemic countries in South East Asia, India reportedly reduced malaria case incidence by more than 55% in 2022 since 2015, but accounts for 66% of malaria cases in the region. In an era of climate change, however, delays or the absence of testing during the non-conventional months of malaria can derail the state’s progress.

“The country has all the best diagnostic tools, treatment, indoor residual sprays and long-lasting bed nets. Implementation must improve and everything we do must be based on sound knowledge of the behaviour of mosquitoes and the transmission dynamics,” said Dhiman, adding that to successfully implement a One Health model like IMACS’, better access to healthcare services for complete treatment is needed, together with health education.

The ASHAs tour the villages, educating people about malaria in the pre- and post-monsoon seasons. However, amongst other challenges, faith in traditional healers make it difficult to follow up every case of malaria, as we reported in the first part of this series.

When Savita’s children fell ill, she rushed them to an ojha (a community healer) to save them. By the time she took them to the community health centre in Chopan, it was too late.

In Makra village, Ankush’s mother still believes that it was the black magic by the “envious eldest daughter-in-law of the family” which took away her son as well as her sister-in-law and her two boys. For her, no other explanation fits for the demise of four people in the family in the span of seven days.

“Any intervention has to be cognisant about the local situation of the residents,” said Atul Kumar, India Program Head - Health in Prayatna. In close-knit communities in Sonbhadra, people refrained from sharing more about their malaria-related experiences with this reporter if they were questioned about their belief in the jholachap doctors. The jholachaps or unlicensed medical practitioners here have the trust of the community. ‘Jhola’ refers to the bag of remedies which the healer carries, which villagers view as a sufficient stamp of authority ‘chaap’ to heal the sick.

“When you tell these communities to not trust the quacks, you are essentially telling them to not trust a person from their community who they see almost everyday,” says Kumar. Prayatna has looped in the jholachaps to report any cases of malaria they see in the villages. This community-inclusive approach is improving malaria case detection by enhancing trust between the community members and healthcare providers, while ensuring quality of care is maintained as per national guidelines and standards at the grassroots, Kumar explained.

Unaware of how to respond to malaria in its early stages, Savita Devi has lost too much. She spends her evenings looking at the mango tree her son Chandan had planted. In her grief, she is oblivious to her other burdens; the mortgage of her land, the debt of Rs 50,000, and separation from her husband Raju, now working in Gujarat to pay off all the debt the family incurred while trying, in vain, to save their five children from malaria.

This story was first published on IndiaSpend, a data-driven, public-interest journalism non-profit.

The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.